How to Quote from this Material

Copyright Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. & Mark Hemry

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

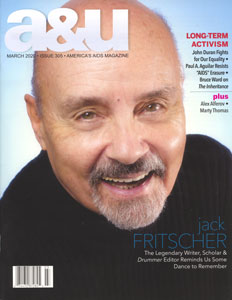

A&U Magazine

by Lester Strong

March 2020

This interview is also available in pdf

Jack Fritscher: writer, journalist, editor, novelist, professor, film (video) director, photographer, as well as gay rights-AIDS-and-leather-culture activist; former Catholic seminarian, ordained exorcist, historian, arts critic, archivist, pop-culture scholar, and founding member of the American Popular Culture Association.... Along the way, he received a PhD in literature from Loyola University Chicago, was a lover and close friend of renowned photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, met and married his life partner Mark Hemry, lived through and survived physically intact the AIDS crisis, and was friends with gay writers, artists, and poets like Samuel Steward (aka Phil Andros), Tom of Finland, and Thom Gunn.

Fritscher has worn many hats in the course of his life and career, and at eighty years old that career hasn’t stopped. But to start at the beginning.

Born June 20, 1939, in Jacksonville, Illinois, and reared in Peoria, Fritscher was raised a Catholic altarboy. “I was groomed from birth to be a priest,” he said when interviewed for this article. “I truly did feel a call to study for the priesthood, hidden away from 1953 to 1964 at the Pontifical College Josephinum [located in Columbus, Ohio] which is directly subject to the Pope.” However, his life did not exactly follow the path he and his family originally foresaw.

“I didn’t see myself as a priest living in a rich rectory with servants,” he explained. “I saw myself as one of the French worker priests who has his own job and lives on his own while simply ministering to people. As a seminarian, tutored by Saul Alinsky [influential American community organizer; 1909-1972], I worked and lived the long, hot summer of 1962 in the black community at 63rd and Cottage Grove going door to door in the same South Side of Chicago in which Barack Obama worked as a community organizer twenty-five years later. It’s true, I haven’t become a priest. I was called to the old school Roman Catholic Church that disappeared with the Vatican Council in 1961 which threw the Church into the conservative turmoil we see today. I couldn’t promise permanent vows of celibacy and obedience to an institution having mood swings about its identity. Instead of becoming the editor of a Catholic newspaper, I’ve become a teacher and writer whose parish ministry is gay culture.”

Fritscher may not have become a priest, but his Catholic education, serious with studies in philosophy, sociology, and especially theology, led him toward an interest in the occult. In his own words: “We seminarians studied the history of the protagonist God and his antagonist Devil. So to give the Devil his due, I developed a journalist’s interest in the occult because people are more superstitious than they are religious. During the Sixties sexual revolution alongside the Catholic Church’s Vatican Council revolution, it seemed worthwhile to research witchcraft as another evolving theology, another church, in American pop culture.”

Interviewing witches, including Satanic High Priest Anton LaVey, across what he labelled the sexual spectrum, as well as what might be called the theological spectrum, he published his 1972 book Popular Witchcraft [Bowling Green University Popular Press] which he described as “about the popular culture of American sorcery.” Again, Fritscher’s words: “I am not a Satanist. I’m a journalist. I’m also a ‘magician.’ Masturbation is gay magical thinking.As an erotic writer, I conjure sex magic to suspend disbelief and seduce readers into transformative orgasm by spelling, casting the ‘spell’ of words into erotic runes that burn the reader down.”

As writer of literary erotica. After years in the 1960s as a tenured college professor at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, he moved to San Francisco, where he had already established a professional presence in his off time from teaching duties in Michigan. Once in California permanently, he moved full time into writing and editing on gay pop-culture themes helping develop some of the first commercial gay magazines like Drummer to be founded after Stonewall.

As portrayed in Fritscher’s Some Dance to Remember: A Memoir-Novel of San Francisco 1970-1982, the 1970s for gay men was one long hedonistic excursion into sex, drugs. and partying, as they celebrated the joyous loosening of social and legal penalties against being gay following the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York City, with the fun being interspersed by political demonstrations in favor of gay rights initiatives and against the homophobic backlash spear-headed by the likes of Christian fundamentalist singer Anita Bryant in Florida and conservative politician John Briggs in California.

The celebratory atmosphere, of course, came to an end in the 1980s with the advent of AIDS. As Fritscher described in the interview, “When the first headlines about ‘gay cancer’ appeared in July 1981, gay character and culture changed. The glorious post-Stonewall celebration of the 1970s ended abruptly. At that time, I was Manager of Marketing Publications and Press Relations at an engineering firm in Oakland. I remember one morning sipping coffee at my desk, I noticed a San Francisco Chronicle article about a gay disease. The threat was more real than Bryant and Briggs and the Moral Majority who prayed for a plague on us. Were we all going to die?”

At the time. Fritscher was well into writing his novel Some Dance to Remember. He had originally conceived it drafted in his personal journals as a “gay pop culture comedy of the first decade of gay lib on Castro and Folsom streets.” But he quickly realized that what he called his “little comedy of manners” had to be re-set “against a larger existential theme.” As a result, “Some Dance became an eyewitness story capturing the almost play-by-play unique moment AIDS arrived and changed how we looked at each other’s faces, bodies, and actions. I lived it and I followed the rule to write what you know.”

For many gay men. including Jack Fritscher, the AIDS crisis also changed their behavior, both sexual and otherwise. Even before AIDS, Fritscher began raising alarms about the state of gay men’s health. “In the 1970s when we all travelled as sex tourists on planes flying the Gay Bermuda Triangle of San Francisco, New York, and L.A., I began noticing health problems escalating in our state of play. No one wants to play Cassandra, but as the responsible editor-in-chief of Drummer [San Francisco magazine (1975-1999), with a monthly press run of 42,000 copies, oriented toward international leather culture], I broke the taboo about never mentioning sex diseases in an erotic entertainment magazine and began writing editorials about sexual hygiene and self-care because I thought a sex magazine was the perfect forum to reach men and promote a change in sexual behavior. At the time, it seemed to me that too many gay men were sick too much too often from too many different things. I wanted Drummer to address the problems to raise awareness.”

The question was would the readers of Drummer and friends Fritscher talked to about the problem take the warning seriously? At least one person did not According to Fritscher,“In late 1979, I warned Robert Mapplethorpe that we all had to clean up our act because, as I told him, ‘I’m tired of everybody always being sick with hepatitis and amoebiasis and clap and crabs and you name it.’ Robert, the Manhattanite, giggled at me, the health nut who got a gamma globulin shot every six weeks and who always took egg-and-orange-juice protein shakes in a thermos for nutrition to sustain marathon nights at the baths. His reply? ‘Oh, Jack, you are so California.’”

Ten years later, in 1989, Mapplethorpe died of AIDS-related causes. It was Fritscher taking his own warnings seriously who remained HIV negative and survived the plague.

Which brings us to the relationship between Fritscher and Mapplethorpe. The two met around Halloween in 1977. “Robert flew to my desk at Drummer to show me his portfolio. He was not very well known then. He needed publicity in a famous magazine. I immediately hired him to shoot a color cover portrait, and later published nine of his photos as a trial balloon [which soon became his X Portfolio]. My international leather magazine needed his homomasculine photos of leathermen as urgently as he needed our thousands of subscribers to grow his fan base when people still thought his last name rhymed with apple rather than May Pole. With a speed fast even in the 1970s, we liked each other instantly and durably for the rest of his life. Our bromance was a bicoastal affair of the travelling kind. We commuted on flights between San Francisco and New York. We wrote letters and ran up immense telephone bills with late-night sex calls and personal talk about life. He was an artist deeply embedded in Catholic ritual and imagery who cast me as a sort of priestly confessor. [In 1978, Mapplethorpe wrote to Fritscher, ‘I think you’re right about me needing a psychiatrist. I’m a male nymphomaniac.’”]

However, it was more than a “bromance” between the two. According to Fritscher, they were “chronologically correct lovers” during the years 1977-1980, after which they “shifted to an abiding friendship over matters of hygiene. Our one and only argument was about hygiene, but it was the beginning of the end of our sex trips.”

The AIDS crisis for Fritscher encompassed more than the death of just one lover and friend — no matter how intense the feelings between them were or how famous the person was. “At the start of the epidemic,” he said,“we thought we all were going to die because we had to endure three agonizing years of intense stress before the first AIDS test arrived to help navigate the nightmare. Every morning, friends would call me and tally up who was sick or dying or dead, and every day I would keep on writing Some Dance to Remember in tears. So many friends died so quickly. Sex tourism stopped. Everyone’s Rolodex turned into the Book of the Dead. Back then, Mark Hemry and I had some extra housing space that we turned into a hospice for a family to live with their son, the media co-chair of San Francisco Pride, who suffered and died there.”

Fritscher met Mark Hemry near the end of his love affair with Mapplethorpe. “We met on May 22, 1979, to be exact,” he recounted, “around twilight, under the bright marquee of the Castro Theater during a demonstration celebrating the first postmortem birthday of Harvey Milk [first elected gay San Francisco Supervisor, slain by fellow Supervisor Dan White on November 27, 1978]. It was a tense atmosphere. Thousands of gay folk crowded Castro Street trying to restore peace in the City after the White Night Riot from the night before when a gay crowd enraged by the light sentence given Dan White by a jury that afternoon attacked City Hall and set police cars on fire — and the police retaliated, chasing all the queers in a running riot back to the Castro, beating their batons on the street, beating pedestrians and bursting into the Elephant Walk gay bar beating patrons.”

He continued, “I asked Mark to come home with me, but he said he couldn’t because he had to study for a molecular genetics exam. I said, ‘I’ve been turned down before, but that’s the greatest line ever. I’m a teacher. I get it.’ When he graduated from San Francisco State three weeks later, we celebrated together, and have now been together forty years — half of my lifetime at age eighty and more than half of his. He’s eleven years younger than me.”

As already intimated, Fritscher and Hemry have been very active around AIDS. More about that later. But they were also active around another important and controversial issue. “In the 1980s,” Fritscher recalled, “we were politically active around gay marriage. We spent years creating a paper trail to boost government statistics proving there was a need and a call for gay marriage. We went through several domestic-partner ceremonies in San Francisco, flew to Vermont the first day of Civil Unions, were married by San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom in City Hall on Valentine’s Day with hundreds of other gay couples in the 2004 Winter of Love, drove to Vancouver the minute Canada approved gay marriage, and in 2008 became one of 16,000 [gay and lesbian] couples married in California before Proposition 8 slammed the window closed [until the U.S. Supreme Court in 2015 declared marriage equality the law of the land]. In the summer of 2009, we took two ‘No on 8’ lawn posters to Paris, where we carried them in the Pride Parade marching with ‘Democrats Abroad’ to the surprised and welcoming cheers of recognition by Parisians of our American struggle for marriage equality.”

As important as the legalization of gay marriage is—and its importance can hardly be exaggerated—the main struggle for the LGBTQ population over the last forty years or so has arguably been about AIDS. In that regard, Fritscher’s and Hemry’s contributions have been immense in several ways. For Fritscher himself, perhaps his earliest contribution was embodied in his Lammy Award Finalist novel Some Dance to Remember. “I book-ended the time frame precisely from 1970 to 1982 to dramatize how the way we lived in the golden age of liberation became the new way we had to be with the arrival of AIDS. [The Advocate reviewed Some Dance as “the Castro’s gay Gone with the Wind.”] One of my goals was to defend 1970s behavior from hysterics who began scape-goating liberated gay male sex as the cause of AIDS. Sex didn’t cause AIDS. A virus did. In 1966, I’d written my doctoral dissertation on eros and thanatos in the plays of Tennessee Williams, so I was schooled in the literature of sex and death. Some Dance is a memory novel balanced on the fulcrum of that July 1981 when we first learned of the disease. I took the title from lyrics in the best-selling album of the 1970s, the Eagles’ Hotel California, which offered a lifestyle choice of affirmation or denial: ‘Some dance to remember. Some dance to forget.’ I chose to remember. The album, played constantly in bars and bathhouses, celebrated the coming of the ‘new kid in town,’ ‘life in the fast lane,’ and ‘lines on the mirror.’ That album became a ‘found’ soundtrack of gay life during the 1970s and continued as a soundtrack into the 1980s, when AIDS turned all gay male space into a viral ‘Hotel California’ where ‘you can check in any time you like, but you can never leave.’”

As editor-in-chief of Drummer magazine, he created a monthly column titled “Doctor Dick” with the help of Richard Hamilton, MD, who in the 1970s treated many gay men in San Francisco. It offered health advice from a doctor who, Fritscher noted, “did not shoot patients up instantly with antibiotics, which the San Francisco Department of Public Health did to every gay man the minute he walked in the door. It’s my opinion that those no-cost 1970s antibiotic shots may have had a lot to do with compromising the immune systems of very many San Franciscans.”

In 1980, Mark Hemry and he started what Fritscher called “the passionate little zine Man2Man Quarterly,” but they closed it down in 1982 soon after the AIDS plague hit the headlines, worried what the take-away might be from the Personal Ads the subscribers sent in which became “disconcertingly dirty.”

Another contribution by the two in regard to AIDS. In 1985 they founded their boutique studio Palm Drive Video with the purpose of entertaining buyers of the solo masturbation videos they produced “to entertain the troops during the viral war” (Fritscher’s words) with images of hot ordinary men, not unattainable porn models, that viewers could identify with as their “date for the night” while the man alone on screen, talking erotically to the viewer, embodied the joys of masturbatory safe sex (“his on screen; theirs in their hand”) that did not require the exchange of bodily fluids. “Palm Drive” was a sex pun, not a street address.

Still another contribution. “To be a functioning eyewitness to the faces of AIDS, at Palm Drive, we also shot many real-time documentaries of street fairs, rallies, ordinary street life, and gay events to show how the disease was morphing the gay body, face, and ‘look.’”

And still another contribution. ‘When the October 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake destroyed the Drummer office, I suddenly woke to the devastating combo of both nature and AIDS on the lives of friends, acquaintances, artists, writers, photographers, filmmakers, and ordinary guys, and began to record their stories, with permission, over the phone. Those recordings are being digitized, identified, and logged right now in the hope that one day they may be valuable to scholars interested in the voices of the first generation devastated by AIDS.”

Fritscher, it’s clear, has created quite a legacy of books, articles, photos, and videos. How does he view that legacy himself? I’m grateful that my sixty-two-year writing career brackets the AIDS emergency by chronicling the way we were in our joy before the plague, during the shocking first headlines about its arrival, and after we learned existential lessons about suffering, compassion, safe sex, acting up, and the problem of evil. I’d be over the moon if the voice in my writing was remembered as literary erotica that started in the head and worked its way down. Sex is the ‘Universal Eternal’ and I hope I captured its twentieth-century frisson on the page so that a hundred years from now a lad can pick up one of my stories and I can reach out from the grave and make him think and cum, and in his seed be alive again.”