How to Quote from this Material

Copyright Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. & Mark Hemry

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

BOOKS TO WATCH OUT FOR

No. 4, October 1994

Newsletter for A Different Light Bookstore

![]()

WHEN MAPPLETHORPE

MET FRITSCHER:

MIRROR BEHIND THE MASK

by James Breeden

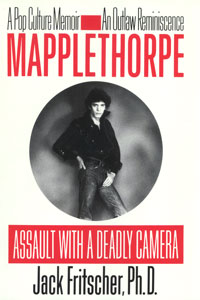

I talked with Jack Fritscher, author of Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera, a memoir on the controversial photographer, in his Sonoma county home, where he lives with his partner, Mark Hemry. It was Mark who video taped us as we spoke in the comfortable living room, in the midst of their art collection, many pieces of male homo/erotic persuasion, often dating back to the 70s when Fritscher was editor of Drummer magazine.

ADL: You could've written your memoir just from your own personal experiences with Robert, but it's actually composed of many interviews from many people who knew him. Why did you decide to take this approach?

Fritscher: I wanted my "take" on Robert to be told, but, at the same time, there are so many people who knew him, and many who are dead. So with only a few left, I wanted to capture those voices--as a scholar of popular culture. I also didn't want it to be the sound of one voice talking.

ADL: When you first met, you were the editor of Drummer magazineand you were also writing yourself. Robert had read some of your pornography and was quite focused on seeking you out.

Fritscher: Exactly. If he was going to plow anybody, he was going to plow like Edward Albee's characters, he was going to plow the pertinent--and at that point in the 70s I was pertinent.

ADL: Talk a little bit about your first meeting.

Fritscher: I didn't know who he was when he literally walked into my office at Drummer, located at the time on Divisadero in San Francisco. Robert did a little shuffle--you know, like when people are auditioning--and opened this big black portfolio with photos. I thought I was in the presence of something that would help raise Drummer out of the purely sexual erotic into erotic art--without losing the heat.

ADL: You saw this immediately.

Fritscher: Oh, yes. He was very modest, saying, "Do you think that you might be able to use one of these on the inside?" And I said: "Listen, I need a cover for an issue. There's this man Elliot Siegal in New York; here's his number." So I sketched the cover for him and he took the assignment. Then he went back east and shot it.

ADL: You have the photograph of that cover in your book.

Fritscher: Right. I gave Robert his first magazine cover. He cannot deny his gay roots.

ADL: Was there any kind of personal connection in that first meeting?

Fritscher: Yes, we went to dinner an hour-and-a-half later, then went to bed. That was the 70s; nobody wasted any time.

ADL: I had the feeling sometimes, while reading the book, that this was a conversation between you and Robert.

Fritscher: It was a long good-bye. You know, when Robert used the term "intellectual sex," I mean, there was a lot of pumping going on, but there was such sharp focus between us. Nothing else existed except that kind of intensity.

ADL: So when you were together intellectually, physically, sexually, you were totally engaged.

Fritscher: He was always there, he was never vacant--even on drugs. The drugs made him even sharper--which is a terrible thing to say in the 90s, but it did.

ADL: Did he really identify with being gay?

Fritscher: He was beyond gay. By the time it had become acceptable, he had moved on to other things. As with most addicts, he wasn't that interested in sex. He liked it because felt good and it got him things, it got him models.

ADL: What did he move on to?

Fritscher: Drugs. And fame. And collecting things.

ADL: He equated sex with money. And power. Being able to collect rich patrons.

Fritscher: His rich patron, Sam Wagstaff, was quite influential in the art and social world of both America and England. He really loved to show off his relationship to Sam and rub other photographers' faces in it.

ADL: Didn't Sam have this vast photography collection where Robert got his education?

Fritscher: Robert was very absorbent. He went to Miles Everett, who first photographed black men in 1931. And George Dureau. Robert gathered rosebuds everywhere. There's nothing wrong with that. Every artist does that.

ADL: Although he has been accused of appropriating other photographer's work.

Fritscher: Even Dureau says that if Robert "took" one of his "takes," Robert put his own spin on it to make it appeal to these nasty New York art types. So Robert just didn't appropriate it. Like fashion designers go to the streets and the clubs to find out what kids are wearing, so that they could take those street designs and turn them into runaway designs, then mass market them. That's all Robert did.

ADL: How long did your sexual relationship last?

Fritscher: It was bi-coastal, and it lasted three years. And then we became friends, because of involvements with other people who more domestic. We were like Fred and Ginger who were meant to dance in the middle of the ballroom on the ship, but never went home and set up housekeeping. We never had any idea of ever setting up the household. For a period in our lives, and in the period of cultural of art and the gay world, we were right for each other. But after it was over we went our separate ways, taking along all the good things, and all the baggage--but with no remorse or no regrets.

ADL: So as Robert became more famous, he became more distant. By 1984, you pretty much just had a phone relationship with him. Did see him after 1984?

Fritscher: No. You know how people say, I didn't see him while he sick so I remember him how he was. I think Robert did that with a lot of people. He did that with me.

ADL: In some of the photographs Robert took of you, he alludes to piercing the mask, and peeling away the layers to get at the truth to a person is really like.

Fritscher: Robert wasn't just a photographer. He was an artist who was a photographer. So yes, as an artist he could find things. He could his artist eye that refracted his own vision. He could peel some things away. But he could also apply things. What did he want me to be time? He wanted me to be Boswell to his Johnson. I was taken along as witness to the accident in progress.

ADL: What was it about you that appealed to Robert?

Fritscher: I let him be himself. I made him go deeper into who he. For instance, when he showed me his photographs I said: "These are fine, but go farther. Use this model, because he will bring to your viewfinder what you're already looking for. What you're looking for is already looking for you, but you have to be pointed in the right direction.

ADL: So you helped focus him in becoming more of who he is, more who he was to become.

Fritscher: Of that leather, demi-monde Robert, yes. And to see the performance art people he saw in the leather world, allowed him to see a leaf even better So that leaf resonates in a way that leaves don't do for anybody else, because Mapplethorpe looked at it.

ADL: Even before AIDS, you told Robert that he would probably die young, most likely suicide, comparing him to Byron and Jimi Hendrix.

Fritscher: Robert would have had to self-destruct. He may have been one of those people who goes out and invites AIDS. If AIDS hadn't come along as a convenient backdrop, than drugs would've done it. He would've ended on an toilet with a needle in his arm.

ADL: And the way he engaged black men.

Fritscher: If he could have been murdered by a black trick, in some famous murder in New Orleans, let's say the way Pasolini was murdered in the ruins of Rome, Robert would have died gloriously. I think AIDS has been a convenient suicide for a lot of people. One way or another, Robert would've exited stage left, it would've been drugs, or a violent hustler. Maybe he would've killed himself.

ADL: There's certainly a lot of the dark side of Mapplethorpe in your book, but you also remember him as being shy, as being very tender, full-of-life, giving and generous. There's that interlude with Mark Walker, the blind artist whom Robert was instrumental in helping return to a creative life.

Fritscher: That's why the Mark Walker piece is in there, because it shows his tenderness.

ADL: And your own personal Robert. You saw his vulnerability.

Fritscher: I felt paternal towards him. I'm seven years older than he.

ADL: One of the reasons why you were able to maintain a relationship with him over the years was because you were one of the few people in his life who was able to say no to him.

Fritscher: Everyone gave in to Robert because he was so beguiling. And I didn't, because my relationship with him was not so much co-equal, outside of sex, as it was one of guidance. He was intrigued by anyone who told him no. The longevity of our relationship was based on that. I tell lots of people no. You can't do that. You can't behave that way. Robert didn't like it, especially since he was a willful artist who was used to getting anything that he wanted. It was like when he called and told me he had HIV. He said: "See, I was just as bad as you said I was." Like he had won something by it. It was this badge of courage.

ADL: Sounds like a rebellious son.

Fritscher: He never grew out of that teenage stuff. It's like the teenager who won't listen about driving the speed limit and goes out and has a terrible accident and kills somebody, or himself, by proving he can drive fast. That's what happened to Robert Therein lies the lesson. Our mothers were right. His mother was right. He should have listened to her.

There's the bodybuilder in my novel Some Dance to Remember. The bodybuilder I knew actually wasn't hustling at the time I was writing the novel. Yet the bodybuilder in the novel hustles. Then later on, the actual bodybuilder I knew ends up hustling, just like the character--but only years after the novel. So Robert got a direction by my saying: "You going to kill yourself." Did I cause this?

ADL: So you've wondered what your role

Fritscher: How much of his movie did I script? I think I was on his shoulder like a conscience. I wanted him to take care of himself. He was still a human being in the same room with me, and I didn't want him to die. I wanted him to be an artist, but not if that's what the price tag was, and I didn't think that was the price tag. He did, though. That's why he gladly paid it. All those people in that generation--Hendrix, Janis Joplin--that was the coin of the realm.

ADL: There's your quote: "Because he was homosexual, lie shot adoring frigid photographs of some females he would have fucked had he been heterosexual." His women may not have been sexual objects, but according to you, he still treated women very similarly as a heterosexual man would--as trophies. There's your bit about how he and Robert Opel would get into this contest about the women they had in tow. Mapplethorpe had Patti and Lisa, Opel had Camille.

Fritscher: Exactly. Their women were both poets and singers. Robert was not a queen, he was not a fag, he did not like fag-hags, these women were not fag-hags. He did not fit into the standard-issue gay man's syndrome. As gay pop culture emerged, Robert saw it as a merchandising venue, and a place to recruit models, but he did not become standard-issue gay man, he never became a Castro clone. He put on leather because the leather got him what he wanted. It was the rock music look. It wasn't a heavy-duty S/M sex look.

ADL: You describe Robert as being basically apolitical, but if you were to describe him you would call him conservative, and that in many ways he shared many of the same values as Jesse Helms.

Fritscher: That's the irony of Jesse Helms' crusade. If he and Robert were in the same room, and no recorders were going, they would have laughed at the same jokes, poked fun at the same people. They basically held the same values. Robert liked to excite the populace in one way, and Jesse Helms liked to incite it in another. To think that Robert was this liberal artist who had great concern for women never happened.

ADL: One of the great ironies is that Mapplethorpe never accepted government money.

Fritscher: Nor was he offered any. He never believed in government supporting the arts. He was a capitalist. He saw government sponsorship of art as censorship.

ADL: In the late 70s, Robert's art was embraced by the gay community but by the early 80s you noticed a shift. I'm talking about the call of censorship within the gay community over the display of Jim Wigler's art in the Eagle. Robert wanted you to do something about it

Fritscher: That article I wrote about that is internally signed with mention of him because he didn't want to get too close to that flame for fear he'd catch fire. He was like a toreador with a photograph, just baiting the bull of gay opinion.

ADL: Was he surprised at the response from the gay community?

Fritscher: He was appalled by it. I was appalled by it. I'm still appalled by it. I'm appalled how it's ballooned to being even worse than before.

ADL: Yet Robert did not want to get involved.

Fritscher: No, because he wasn't an activist. All he wanted to do is sell photographs. That's why he left the gaystream behind because the straight stream of art had not picked up on this political correctness, but the gaystream had. So he began to avoid this by taste, then by design. It was too small a battle and venue, he was on to bigger things. He was already selling photographs that your average gay guy couldn't afford.

ADL: So what do you think Robert would have thought about this censorship over his art?

Fritscher: I can only quote Liza Minnelli and Joel Grey: "Money!" If he had known that he would've gotten so far as to have turned the government on its ear, to have caused the Senate to stand still while they debated a photograph he had taken, that would've been the biggest high he ever had in his life. That would've been better than having a hit of MDA, a gun in his mouth and a "nigger" holding it.

ADL: You quoted George Dureau, when he and Robert went out tricking, and Robert came back the next day, dissatisfied, because he had picked up a black man who wouldn't say to him--

Fritscher: "--I's your nigger."

ADL: Yes.

Fritscher: When I use "nigger" in this interview, I'm using it in terms of how Robert used it.

ADL: So what did Robert mean when he used the word "nigger"?

Fritscher: A sex slave. From the old plantation. He had this American thing that's loaded with all the emotional fervor of racism and the power of sexuality. He used blacks because he needed to act out this charade of whiteness, this positive and negative of the photographer. His whiteness needed to play with this blackness. So it goes almost from literal racism, which it was, to metaphoric apology--which is almost like the people in the South saying: "oh, we love our slaves," but still the slaves have to put out at night when the "massah" comes out to screw them.

ADL: Robert never wrote about his photography. Do you think it's odd that a man who needed to be so much in control wouldn't want the last word?

Fritscher: I don't think he could. Robert couldn't write. I think he was dyslexic. I don't think he could read all that well. He was visual, not verbal. He needed Patti Smith, Joan Didon, Ed White to write prefaces to his photographs because he couldn't write word one. He could not interpret himself. He could take autobiographical pictures and say: this is who I am and how I want you to perceive me--but he could not elaborate on that.

But Robert's subconscious was working even while his consciousness was working.

ADL: Isn't that the definition of a great artist? One who can allow his subconscious to come through in their art?

Fritscher: That's why he's so scary. He triggers this in the conscious and in the subconscious of people. Because his art is so rich and basically about death, sometimes posing as eros. When Jesse Helms looks at it, he becomes terrified in the Jesse Helms way, when somebody else looks at it, they become pleased in their way, or thrilled or hilarious, depending on what you bring to his photography. In one very famous set-up he had placed in a frame three photographs--and one of them was a mirror. So as you looked at it, suddenly you were looking at yourself. His photographs in the final analysis were nothing but Rorschach blots. He presents you with one literal thing, but you see what you want. I'll be showing you something, but you'll always be looking at yourself.

ADL: You think that Mapplethorpe will be viewed differently in five to six years. How so?

Fritscher: There'll be a Mapplethorpe postage stamp. Jesse Helms will have to lick Robert's Calla lilies. He'll become mainstream. Look at James Joyce's Ulysses. Once anyone becomes a classroom assignment, immense yawns set in. Mapplethorpe is already on curriculums.

ADL: There's a huge quantity of photographs that haven't been viewed by the public. A self-portrait in black-face, the scatology

Fritscher: He left a monument after himself. It's not like you can go rooting through drawers to pull together what he's got, because there's security guards standing in place. Putting out this unseen material is the kind of stuff that they'll be merchandising. So this merchandising of Mapplethorpe precludes knowing what's actually there, and what will be released when. His work is like the message at Fatima. We'll know by 2020, maybe.

ADL: So when you, personally, peeled back his slick commercial surface, this cold classical form, what you found in his art was this raw primordial heart.

Fritscher: He was a wild heart. And he was a wonderful one. And it's terrible with him being dead.

©James Breeden & Jack Fritscher