NON-FICTION BOOK

by Jack Fritscher

How to Quote from this Material

Copyright Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. & Mark Hemry - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

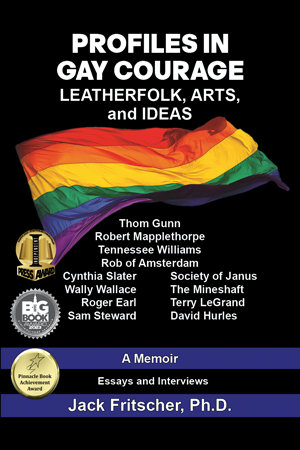

PROFILES IN GAY COURAGE

Leatherfolk, Arts, and Ideas

Volume 1

by Jack Fritscher, PhD

Also available in PDF and Flipbook

TERRY LEGRAND

1939-2018

BORN TO RAISE HELL

Once upon a time, there were no gay movies

Pioneer gay film producer Terry Rodolph Grand was born to raise hell as “Terry LeGrand” in Denver in 1939. He died from AIDS complications at his West Hollywood home April 18, 2018. The Tom of Finland House honored his life with a memorial garden party in Los Angeles on June 3. As the founder of Marathon Films, Terry produced the classic leather film Born to Raise Hell (1975) directed by Roger Earl starring their discovery, Val Martin, whom Drummer editor Jeanne Barney featured on the cover of issue 3. Born to Raise Hell and Drummer opened the closet door on leather, kink, and BDSM.

At the violent police raid of the “Drummer Slave Auction” on April 11, 1976, the foursome of friends (Terry, Roger, Jeanne, and Val) were among the 42 arrested — partially because fascist LAPD Police Chief Ed Davis knew Drummer was promoting Born to Raise Hell which Davis decreed would never be screened in Los Angeles. Davis was a documented fuckup. He knew how to entrap fags and bust fairies. But he couldn’t stomach the new breed of homomasculine leathermen who looked more authentic in cop uniforms than did many of his officers. When his late-night storm troopers cuffed the straight Jeanne Barney, they asked if she was a drag queen, and she snapped: “If I were a drag queen, I’d have bigger tits.”

Harassed in LA by Davis who called him into his office, Terry told me Davis pounded his desk and threatened him against screening his film at any theater in LA. So Terry moved the world premiere of Born to Raise Hell to San Francisco at the Powell Theater, near the Market Street cable car turn-around, where we first met on the Leather Carpet in June 1975.

Terry and Roger, never lovers, were dear friends to each other for forty-four years, and Terry was the sole owner of Marathon Films. They met while Roger was working behind the scenes at NBC Television in Burbank in 1974. Roger was a guest at one of those ever-so patio parties in the Hollywood Hills where the talent stood on one side of the pool and the wallets stood on the other. It was the kind of backstage sex-mixer described by party host Scotty Bowers in his book, Full Service: My Adventures in Hollywood and the Secret Sex Lives of the Stars.

At that soiree, Roger’s erstwhile leather-bottom George Lawson, who had gotten him his job at NBC, introduced him to Terry who needed a director for his new S&M leather picture. Lawson who was originally slated to direct the film told Terry that Roger would be a better choice because of his stage experience at NBC.

Remembering that night, Roger told me that driving back to his West Hollywood apartment where he has now lived for more than fifty years, “The title Born to Raise Hell just came to me. I pictured a motorcycle guy with a tattoo.”

Roger wanted to find a Brando, like Marlon in The Wild One, while Terry wanted to find a cast as authentic as Kenneth Anger’s in Scorpio Rising. As a double-bill, those two films can represent a prequel to Born to Raise Hell. That lineage makes a trilogy of masculine-identified films that looked virile and made thematic sense screened together.

“I needed a really dynamic guy,” Roger said, “to carry this movie. Otherwise it was going to be the same old shit. Terry couldn’t have agreed more. I thought of the Colt model Ledermeister, but he was not into the S&M scene. I was lucky to find Val Martin tending bar. He scared me, and I’m a top, so I knew he was perfect for the part of ‘Bearded Sadist.’”

Terry’s casting of authentic leathermen recruited from LA bars made Born to Raise Hell a transgressive play-within-a-play like Jean Genet’s The Maids and The Blacks. Not that Terry or Roger were film students particularly aware of Genet or the coincidence. Just as Genet’s poetic, sensual, homomasculine S&M prison film Un chant d’amour (1950) was declared obscene by Berkeley, California, police on its American release in 1966, Terry’s brutal X-rated S&M cop-and-biker film would be censored and prohibited in 1975 by Los Angeles law enforcement.

The climax of both films, made twenty-five years apart, is a sex chase through the woods. In Genet’s film at the climax, a cop forces a gun into his victim’s mouth; in Terry’s film at the climax, the cop forces a nightstick into the victim’s anus. In his meta film, Terry cast non-actors role-playing themselves as characters who are themselves. Years and years before reality TV, that practicality was his genius. In 1975, the LA cops saw Born to Raise Hell as a depraved fag movie; but the new leathermen coming out of the S&M closet to be born again in kink saw it as a sex-education film.

This raises the question: are gay porn films fantasy fiction or authentic documentary? This ambiguity alarmed Davis, who feared the film was real, and charmed Terry, who knew it was. The 1960s cultural revolution was in the 1970s air. Shot in the styles of Mondo Cane and Scorpio Rising (both 1963), Born to Raise Hell is also a perfect backstory of William Friedkin’s controversial S&M film Cruising (1980) with which it makes an adventurous cinema quartet.

In the LA gay press, Drummer called Davis “Crazy Ed” after he went on local television news demanding a portable gallows to hang captured skyjackers on airport tarmacs. He was riding high on his horse because he had recently arrested the Manson Family for the torture murders of pregnant Hollywood actress Sharon Tate and her friends which confused him about sadomasochism and consent. He reveled in his famous shootouts with the Black Panthers and with the Symbionese Liberation Army, six of whom in 1974 he had burnt up in a house fire he set trying to arrest them for the kidnap and torture of newspaper heiress Patty Hearst who later made a camp of herself in John Waters’ films Cry Baby and Serial Mom.

Terry dared produce his erotic leather documentary in LA despite Crazy Ed raiding leather bars, tapping phones at Drummer, and freaking out over the two “cops” in Born to Raise Hell, and the high-profile coverage of the film in Drummer. Like the politically-correct myopic gays who ran screaming “rape” from the Powell Theater premiere, Davis confused the film’s consensual S&M action, including the wild cherry-popping fisting scene, with violence. He feared being played a fool by fags. He inspired gay resistance. Terry along with his friends Drummer publisher John Embry and leather author Larry Townsend became his nemeses in gay media. Drummer columnist Guy Baldwin, Mr. IML 1989, penned a pertinent commentary about gay fundamentalist opposition to leather culture in Drummer 168: “Beware of the Politically Correct Sex Police.”

From the 1970s onward, Terry led local gay resistance on several fronts as a political activist, filmmaker, and host of his chat show on LATalk Radio, and as the founding president of the Gay Film Producers Association.

For LATalk in 2010, he created two shows. For the first, The Alternative, he hosted personalities like Carol Channing, Armistead Maupin, Johnny Weir, Peter Berlin, and Tyler McCormick, the first transgender Mr. International Leather who was also the first Mr. IML to roll across the stage in a wheelchair.

For the second, Journey to Recovery, he called upon his “twenty-five years in the addiction field.” Roger claimed that during the AIDS emergency, “Terry felt he would be able to better serve his community by becoming a doctor. He went to school and received his degree.” The Alternative called him a “retired physician,” but what school, what degree, and what kind of doctor remain to be detected.

Terry was also a stage hypnotist at C Frenz, the longest operating gay and lesbian bar in the West San Fernando Valley which advertised: “Master Hypnotist Terry LeGrand Hosts Charity Show, C Frenz, Reseda, CA. Terry LeGrand brings campy hilarity to his hypnotism show, performed live on stage the first Sunday of every month. Come see one of the gayest and funniest shows around. Guaranteed to entertain you and your friends. Hysterical and real the first Sunday of every month starting at 9:00 PM Reservations are recommended.”

It is true that in the 1980s, Terry and his friend Robert Bonin created the AIDS/HIV Health Alternatives, “Forming Opportunities Under New Directions” (FOUND), which opened Menlo House, 1731 S. Menlo Avenue, offering, from his own experience, recovery maintenance to drug-addicted ex-convicts with AIDS. Terry was a recovering alcoholic like his longtime friends Jeanne Barney and Larry Townsend with whom he and Roger lunched for years at the French Market restaurant at 7985 Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood which was their stomping ground.

On his radio show, often hosting in tandem with Will Meyerhofer, JD LCSW-R, “The People’s Therapist,” he used his experience to encourage his audience to keep conscious of the real impact of alcohol and suicide on gay lives, especially in mixed HIV-status couples when beset with holiday blues. His other topics covered kinky sex, gay therapists for gay persons, gay adoption, ACT UP/LA, Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, dating and internet dating, being gay and Christian, and misconceptions gay and straight people have about each another.

The money-spinning producer of almost thirty films like Gayracula, Men of the Midway, and Pictures from the Black Dance, was as provocative off screen as he was on. In 1991, he produced what Dave Rhodes at The Leather Journal called the best-ever regional Mr. Drummer Contest. Rhodes then added: “LeGrand received heavy criticism for what some said was $40,000 he spent on promoting and producing the event while others were awestruck by the production that rivaled the finals in San Francisco.”

What great character has no flaw? Like Genet who was, in Steven Routledge’s words, “an odd hybrid: part criminal and part literary celebrity,” Terry, who sewed many panels for the AIDS Quilt, often caused people to ask where the money went because Terry like John Embry had a touch of larceny about him, often of the amusing kind found in British film comedies of the 1950s. Terry was famous for writing bad checks which is a misdemeanor crime for amounts under $950 in California. When some folks, including crew from one of his films, went to the LA County Sheriffs who were empowered to collect funds owed in bounced checks, a deputy reported back, delivering the money owed, saying she had never met a character like Terry LeGrand in her entire career.

Somehow, it was funny that Terry had in him a bit of Max Bialystock from Mel Brooks’ The Producers, and few grew angry at him who, like Max, slowly made good on his debts. When he contracted me in spring 1989 to shoot three films with a single camera in Europe, I suggested he also hire my husband, film editor Mark Hemry, for a two-camera shoot to get better coverage to make a visually richer movie because Mark and I shot in a matching style, and he would be perfect to handle technical design for lighting and sound.

Money was never an issue between us because we told Terry that in exchange for his footing our travel, food, and lodging expenses, he would not have to pay us to shoot the videos.

With that satisfactory arrangement, instead of editing our two cameras together as action and reaction shots, he and Roger — mindful of Hollywood sequels — felt free to look at our hours of footage, and, instead of the three movies, cut six. That’s the inside story of how their trilogy, planned to match their 1988 Dungeons of Europe trilogy, became the six titles in Marathon’s Bound for Europe series.

As happened in the karma and chaos around AIDS, those six films we shot for them were their swan song. They were the last movies Terry produced and Roger edited.

Terry was a business man, a showman, a producer, an impresario. In Europe, he generously lodged us crew in hotels like the grand Victoria Hotel in Amsterdam on the Damrak across the street from the Amsterdam Centraal Station. He wasn’t an artist or an auteur filmmaker, but he, who was Co-Chair of ACT UP Southern California, was a dedicated force in film, politics, and AIDS. And he was kind, fun, and fair.

As president of the Gay Film Producers Association, he told The Los Angeles Times that erotic filmmakers like Catalina should practice what they preach when they put a caution warning about safe sex on a cassette that contains a film showing unsafe sex. Putting a caution label on a film glamorizing unsafe sex “…is stupid. We have to stop making films with unsafe sex in them. The dollar cannot be important to us. Saving lives has got to be the important thing.” In affirmation, Drummer publisher Tony DeBlase wrote of Terry’s Pictures from the Black Dance: “…the 1988 action is much closer to 1975’s Born to Raise Hell …and still all safe sex! Like Born to Raise Hell, this Dungeons of Europe trilogy will be one of the major contributions to the erotic media for SM men.”

On The Alternative broadcast on January 10, 2011, Terry counseled: “For many in our community, there’s a second coming out that’s less fun, but equally important — coming out as HIV+.” In 2012, he and his radio show were cited in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 102, issue 4, in Sharon Dolovich’s article: “Two Models of the Prison: Accidental Humanity and Hypermasculinity in the L.A. County Jail.”

Hypermasculinity, often caused some say by XYY chromosomes, is a toxic exaggeration of normal primary and secondary male sex characteristics. It is not a synonym for XY homomasculinity which is a natural human expression of male gender that, far from canceling the female principle, offers the valid gender balance of man-to-man male animus that respects what the female anima demands and deserves.

In the 1980s, Terry’s annual Producers Awards Show at the Hollywood Century Theater at 5115 Hollywood Boulevard gave “Oscars” to the best erotic films with proceeds going to the support of the Gay and Lesbian Community Center. Terry had a soft spot for the Hollywood Century that had become a gay adult theater a decade before on November 21, 1973, with the premiere of director Richard Abel’s big box-office hit Nights in Black Leather.

That film starring the already iconic Peter Berlin became a kind of template for Terry who smelled money, and immediately understood its episodic documentary style following Peter cruising through his life in San Francisco. Terry had considered casting the popular Peter Berlin as a lead in Born to Raise Hell, but Roger thought Peter, who was best as a solo performer, too young, too blond, and too sweet. In 2008, the magazine Gay Video News, sponsor of the GAYVN Awards, inducted Terry into its Hall of Fame, and in 2009 granted Roger the GAYVN Lifetime Achievement Award.

As birthday twins turning fifty in 1989 in Holland, Terry and I laughed with Roger Earl and Mark Hemry on the evening of June 20 when Terry spontaneously jumped up and joke-kissed me to great hilarity while we were chatting on a little supper boat cruising the canals of Amsterdam. Terry was born thirteen days after me in summer 1939, and like an existential punch-line two months later, Hitler invaded Poland. The joke was on us. So was the violence we had to process as children.

Born into a world dangerous to everyone, and always more risky for gays, we war babies who became teenagers in the homophobic 1950s were all too aware there were no gay magazines or movies. Then came Stonewall. By the 1970s in our thirties while the shameful real violence of the Vietnam War wound down, Terry was the producer of the “violence” in Born to Raise Hell, and I was the editor of the “action” in Drummer. It was our generation of war babies who alchemized real-life toxic violence and empowered the 1970s culture of liberating resistance with the curative of orgasm.

My own attraction to BDSM was counter-phobic. I eroticized what scared me. People naturally do that. The violence of the Second World War became insanely surreal with the kind of terror that can only be survived by making it erotic. I wanted to turn sex into art because art makes sense of life. Born to Raise Hell is the fever dream of war baby counter-phobes ritualizing action that discharges fears by making them erotic.

Talk about performance art! Talk about disruption of the norm! Terry dared put this kind of ritual cleansing up on the screen to address and relieve gay fear. Born to Raise Hell is a horror film with “happy endings” on screen and in the audience. At that packed Powell Theatre premiere, leathermen openly masturbated. Safely. Because if gay fantasies of dominance and submission came true, they’d be nightmares. Every pornographer knows that orgasm is the best review.

Marathon’s films were “conceived by Roger Earl,” but were unscripted. That’s what made them such wonderful accidental documentaries of real leather life. “Terry and I preferred to let guys do their own thing on camera to keep it real.”

Roger remembers Terry as a mindful producer. “I give a 1000% credit to Terry. He was the one with the guts to dare go out and hire the cast. I’d say ‘I want this one’ and he’d go convince the guy. Remember: this was back in the day when gay men feared cameras as tools of blackmail, and nobody had yet really seen a gay S&M leather movie. We worked wonderfully together.”

That production summer of 1974 was a key turning point in the birth of the commercial gay porn-film industry kick-started in the 1940s by Bob Mizer at his Athletic Model Guild studio in Los Angeles, and in the 1950s by leather kingpin Chuck Renslow at his Kris Studio in Chicago. Terry wanted to earn big bucks at the box office because money and fame empower visibility, and he enjoyed the good life. On location in 1989, I remember him standing in the hallway at the Victoria Hotel showing us his latest high-tech toy, a tiny new camera that he said did not use film and would revolutionize photography. He was an opera buff who dreamed operatic porn dreams after watching Deep Throat break through to make millions in 1972.

As a marketing activist, he was keen to fill gay gaps and loud gay silences. He fused trends. He saw an unserved audience of leathermen standing in bars eager to see themselves on screen, but not in the sleazy way San Francisco leather bars were portrayed as special rooms in hell in the 1973 Hollywood film, The Laughing Policeman. He understood the red-hot popularity of Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising and Fred Halsted’s LA Plays Itself. Why not produce a film to uncloset bondage, fisting, cop worship, and S&M for that audience wanting authentic identity entertainment seeing themselves on page and screen?

For the same reasons at the same moment, Terry’s lifelong frenemy, John Embry, founded Drummer. That film and that magazine suddenly gave masculine-identified leathermen visions and voices and visibility. For instance, in the Drummer personals ads written by grass-root readers profiling themselves and the sex partners they sought, the most repeated words, by count, were masculine and masculinity. In perfect synergy, the producer needed Drummer to publicize Born to Raise Hell, and the publisher needed stills from the film to fill Drummer.

Drummer published so many photos from Terry’s films on covers and on inside copy that it sometimes seemed like a LeGrand fan zine. Covers included Drummer 3, October 1975, Drummer 114, March 1988; Drummer 125, February 1989; Drummer 147, March 1991. Interiors included Drummer 2, August 1975; Drummer 3, October 1975; Drummer 78, 1984; Drummer 116, May 1988; Drummer 126, March 1989; Drummer 133, September 1989; Drummer 137, March 1990; Drummer 141, August 1990. Drummer also featured photographs I shot in Europe of his work on the covers and interiors of its Super Publications: Mach 20, April 1990, and Tough Customers 1, July 1990.

When the Museum of Modern Art in its own fever dream inducted Halsted’s S&M-themed LA Plays Itself into its permanent collection in 1975, that validation gave Terry a green light more certain than the great Gatsby’s to follow his commercial passion. Politically, Terry had no question about his rights as a gay filmmaker. Nor did Roger or Halsted. “We would never have made it,” Roger told me, “if it hadn’t been for Fred putting out LA Plays Itself.”

In Beyond Shame, Patrick Moore observed in 2004: “What is being explored in both films is a kind of sex that depends not only upon erections and ejaculations, but rather on an emotional stretching that remains shocking today, but must have seemed nothing short of revolutionary in the early 1970s.” He is correct. At the Powell Theater premiere, the invited audience gave a standing ovation calling out for more.

LeGrand-Earl helped grow that “emotional stretch” (literally in a fisting film) dramatizing men bonding together in the special trust of leather psychology. In that post-Stonewall decade of emerging liberation, the new gay S&M porn, like sadomasochism itself, was roaring out of the closet and into the art of popular culture. Terry calculated that mainstream producers and directors were educating gay and straight audiences into sadomasochistic literacy with international hit films like The Night Porter, Salo: a 120 Days of Sodom, Seven Beauties, and the camp Ilsa: She-Wolf of the SS.

Because Terry and Roger made Born to Raise Hell as equals, they deserve co-star billing, but, as often happens in Hollywood, one name can outshine another, and reviewers and queer historians seem to side with French auteur theory which identifies a movie by its director: a Truffaut film, a Hitchcock film. Terry and Roger deserved double-billing like Ismail Merchant and James Ivory, but self-effacing Terry, who produced twenty-two of their films, made Roger the star in their advertising, which buried Terry’s name in Marathon publicity.

It was Terry who planned and coordinated the actual film production for Born to Raise Hell. He created the safe environment needed in order to work free from harassment by Davis. It was Roger who helped Terry finance this little gay art film with a personal loan of $10,000 dollars from singing star Dean Martin while Roger was Martin’s dresser and production coordinator on The Dean Martin Show at NBC. (Martin, who liked Roger, did not ask what the loan was for.) Terry protected Roger, and the cast and crew Roger directed, including Tim Christie, one of the incestuous pornstar Christie twins, as sound recordist, and Ray Tomargo and Vince Trainer as the cinematographers.

Terry managed their shoot on location outdoors in Griffith Park, and inside the old Truck Stop bar way out in the San Fernando Valley. With a half-dozen reels in the can, while Terry held his breath, Roger spent four risky weeks in post-production guiding Trainer in cutting the 16mm Eastmancolor footage on a Moviescope set on Roger’s kitchen table. “It was dangerous,” Roger said of those analog-film times, “Because we could not afford a work print for back up, I was cutting the negative of the original 16mm footage, and didn’t want to screw it up.”

In 1988, as a grand finale to cap their life’s work in LA, Terry decided to use their international success with Born to Raise Hell as a calling card to hire European leathermen and locations by traveling to London to shoot Marathon’s first three-film series, Dungeons of Europe, with British tattoo-and-piercing artist Mr. Sebastian opening his studio for the first of the trilogy, Pictures from the Black Dance, after which they flew to Amsterdam to film Like Moths to a Flame and Men with No Name. At the height of the AIDS emergency, a new generation of film fans got hard on kink offering safer-sex. Everything old at Marathon was hot again.

Trying to remake and upgrade the intensity of Born to Raise Hell, Terry banked on finding more of the sex-magic he’d found in Europe in 1988. He could rely on his director and he needed a reliable cameraman to shoot the cast of local men he’d recruit in bars. So in 1989, Terry hired Mark and me because he liked the cinematography we were shooting for our Palm Drive Video studio. We also bonded in that moment because our mutual friend, Fred Halsted, had just committed suicide. Flying to Amsterdam, we four traveled on a wild month-long shoot for our six-film series, Bound for Europe, documenting Dutch and German S&M: The Argos Session, Fit to Be Tied, Marks of Pleasure, Knast, The Berlin Connection, and Loose Ends of the Rope.

Our simultaneous two-camera shoot was a first for Marathon Films. Terry credited two cinematographers for Born to Raise Hell, but the two took turns shooting with one film camera. Terry and Roger were pleased we shot enough digital footage to keep Roger busy at his editing console cutting the six films over the next two years.

Four months before the Berlin Wall came down, something sexually electric and wonderfully debauched was in the air because the men and the bars and the action seemed very Weimar! Very Cabaret! It was romantic being part of a film crew shooting leathermen on location during the last summer West Berlin existed.

In a way, the Second World War was also not over for some German war babies. One afternoon, Terry and Mark and I walked to the city center to shoot exteriors of the bombed-out Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church on the famous Kurfürstendamm, the Champs-Élysées of Berlin. The pile was a tall gothic ruin preserved behind a chain-link fence as an anti-war memorial. Suddenly, two young German punks with spiked hair barged into our shoot, pointed at the ruined church, and said, “See what you Americans did?” I looked up from my viewfinder and said, “You started it.” That ended that conversation.

That July, we eyewitnessed the efficiency of Roger and Terry working together. Terry assembled an exhibitionist cast eager to do their own thing. Roger put the men — like the East German sex-bomb Christian Dreesen, who needed little direction — on set, and yelled, “Camera. Speed. Action.”

Roger was an engaged director when we shot with large casts in the main rooms of bars. Thinking of the fourteen-year-old Born to Raise Hell, he set out directing his standard vision of American-movie S&M until he relaxed as much as he could and let the cast do their improvisation from life of authentic German S&M which was the fresh new thing Terry and he said they wanted. Oftentimes, Mark and I, lying on the floor filming only six inches from the action were impressed with the hot German ingenuity and severe intensity.

Once while we filmed in the funky cellar of the Knast bar, Roger retreated to another room where, nursing a beer, he quietly watched the S&M talent on Mark’s live feed from our cameras to his video monitor. By that time, he’d learned to leave well enough alone. He gave no direction, and couldn’t be heard if he had. The soul of cool, he simply watched what the leather masters and slaves did best until he figured we had shot enough running time for the scene, and he yelled “Cut.”

Neither Roger or Terry ever said one word about how we should shoot the movies because they wanted a Palm Drive video inside a Marathon production. We had no intention of repeating the straight-on declarative 1970s shots of Born to Raise Hell. So we added some of the italic Palm Drive flair we’d been hired for. We decided to shoot these 1980s films from the tilted point of view of an audience tripping on acid.

In Amsterdam, Terry produced a location whose heritage and realism inspired the actors. At the dark hour of 2AM on a two-night shoot, we began filming The Argos Session inside the Argos Bar documenting that midcentury interior gay bar that opened in 1957 and closed in 2015. I remembered that sex pit fondly from 1969 when I had slept in a rented room for a week backstairs at the Argos on Heintje Hoekssteeg, where on one long rainy spring afternoon, I amused myself by letting some dude tattoo my taint as a permanent souvenir.

By 1989, the wooden floor in the Argos bar and the road-asphalt coating the floor in its sex cellar were so filthy, we told Terry we could not get down on our knees or lie on our bellies to shoot exotic-erotic angles. To travel light, we had packed only a few changes of clothing. So Terry bought us Class 6 Hazmat suits that protected against toxic and infectious substances that solved the problem because it is hard to do laundry on a trans-Europe road trip in a time of viral plague.

Terry had expected me to shoot video and stills, but I told him, after shooting both the first night in the Argos, it was impossible to stop for stills without interrupting the flow of the video. We recommended he contact the London photographer and painter David Pearce who had shot the stills the year before for the Dungeons of Europe trilogy. From that first night’s shoot, I remember a signature photo I lensed specifically to illustrate Marathon’s VHS video-box cover glamorizing the two stars of our cast standing on the stairs in the historic gay space of the venerable Argos. Terry liked it enough to publish it on the cover of the Drummer sibling magazine, Mach, issue 20, April 1990, along with twelve more of my Argos shots inside the issue.

Leaving Holland, Mark was the only one skilled and brave enough to drive our rented Mercedes van, speeding with six passengers (Terry, Roger, David Pearce who was our translator, production assistant Harry Ros of Rotterdam, Mark, and me) through the terrifying traffic on the Autobahn, so we could film in Dusseldorf and Hamburg by way of Cologne where we did not shoot.

Terry left us for two days in Cologne shooting exterior shots for the final edits while he traveled ahead by train to Dusseldorf scouting models and securing our one-film shoot in a dominatrix’s straight S&M brothel. When our filming there ran overtime, the leather ladies of Dusseldorf waited patiently off camera watching, smoking, whispering, and, finally, applauding.

In a private gay S&M dungeon Terry rented in Hamburg, we shot one and a half films. Because of international treaties limiting how many Americans could be in West Berlin at one time, we had to leave the van and fly over East Germany to West Berlin where we shot two more features in two gritty wunder-bars, the Knast and the Connection, on Fuggerstrasse, Schöneberg.

1. Argos: The Sessions, shot in Amsterdam

2. Fit to Be Tied, shot in Dusseldorf

3. Marks of Pleasure, shot in Hamburg

4. The Knast, shot in West Berlin

5. The Berlin Connection, shot in West Berlin

6. Loose Ends of the Rope, a compilation from extra footage shot in Amsterdam, Dusseldorf, Hamburg, and West Berlin

Terry booked us to shoot after 2 AM in so many abandoned rooms and brick-strewn cellars lacking even toilet facilities that tension broke out with the ever-changing cast who wanted more pay for play. What film shoot does not go over budget? We were well fed and lodged, but no longer staying in hotels like the Victoria in Amsterdam. The actors were paid equitably, but some gimlet-eyed leathermen wanting more American dollars trashed Terry for his tight bankroll just as some trashed Roger for his Hollywood hauteur. Roger won no fans accusing everyone in the West Berlin cast of stealing a wallet, it turned out, he had lost himself. Mark and David Pearce and I, staying clear and becoming fast forever friends, dubbed the European shoot “Trouble in the Rubble.”

At the end of the tour, David, who was a noted London painter living on the dole, flew home with us and stayed a month while he painted our portrait on an easel in our Palm Drive studio.

During the nights after every shoot, Terry was happy that Mark, on his own initiative, woke every two hours to make copies of the day’s hours of original footage so there would be two copies in separate luggage in case the tapes got confiscated in German or American customs. At that time to get in or out of West Berlin, which was a post-war political island surrounded by East Germany, every traveler had to go through East German customs run by iron-handed Communist women in uniform. It was the last exciting and romantic summer in a nervous West Berlin just a hundred days before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

As a publicity stunt for advertising, Terry wanted to shoot in East Berlin, but at Checkpoint Charlie we turned around because no one on the crew, except Terry, felt it was safe for a Mercedes full of gay pornographers to cross over to East Germany to solicit East German men to beat each other up for a decadent American film studio. The East German secret police, the Stasi, were not disbanded until the next June in 1990.

Instead, on our last night in West Berlin, something fun happened during our farewell supper that the generous Terry hosted in the Michelin-starred Restaurant Bieberbau on Durlacher Strasse 15. Its awesome interior that survived the war was famous for its dramatic dark beams and dazzling white plaster walls sculpted with high- and low-relief flora and fauna showcasing the figurative stucco work created in 1894 by German master-plaster sculptor Richard Bieber.

Over dessert, a hot young Berliner on our crew asked if we would like to go scream under the arch of the elevated railroad bridge at Bahnhof/Station on Bleibtreustrasse at Savignyplatz, ten minutes by taxi, where, in the almost-perfect movie Cabaret, Liza Minnelli taught Michael York how to scream their bloody howl against the coming fascism.

After a month of very long nights on set, it relieved our stress and anxiety. After all, during that month, with AIDS rampant, we were living a pure zipless fuck. We had no sex with any of the tempting locals or with any of the cast whose sex we sucked up untouched into the camera to give all the sex to the viewers which was our job.

Roger and Terry didn’t care a fig about Cabaret. From his days with Dean Martin in Las Vegas, Roger announced at the candle-lit Bieberbau table he wouldn’t go scream because he hated Dean’s co-star Liza. But Mark and David Pearce and I, HIV-negative in an age of incurable viral plague, had reason to scream. We waited breathless, stoned on grass, leaning against the brick wall under the viaduct bridge for a train to roar past over our heads and we screamed till our screams turned to laughter. For Christmas 1989, Terry sent each of us a small souvenir chunk of cement that he said was from the Berlin Wall.

In 1991, Terry founded Parkwood Productions with Louis Jansky, and became the founding publisher of Leatherman Magazine whose title he wrote in International Leatherman, issue 2, 1994, he took from my novel Some Dance to Remember. Capitalizing on Leatherman in 1994, he sold the title to Brush Creek Media in San Francisco who were the publishers of Bear magazine. He closed Marathon when he broke his hip in 2007. He was pleased in 2017 when Marco Siedelmann’s Editions Moustache in Germany published my photos of him and Roger making the last films of their careers on location in Holland and West Germany in the book California Dreamin’: West Coast Directors and the Golden Age of Forbidden Gay Movies.

In France in 2017, Neons Fanzine #3 invited a new next-generation to tune in to view the enduring Born to Raise Hell and a similar rough S&M documentary, Jean-Étienne Siry’s Poing de Force [aka The Warehouse aka the glorious 1976 fisting film Erotic Hands] which “…are each a tasty experience to enjoy at least once in your lifetime. These grimy and nihilistic pieces of sleaze are a great opportunity to let you, through their mondo-style filming and dirty, gritty picture, dive into the leather underground subculture where Hell is Heaven and pain is the key…”