NON-FICTION BOOK

by Jack Fritscher

How to Quote from this Material

Copyright Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. & Mark Hemry - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

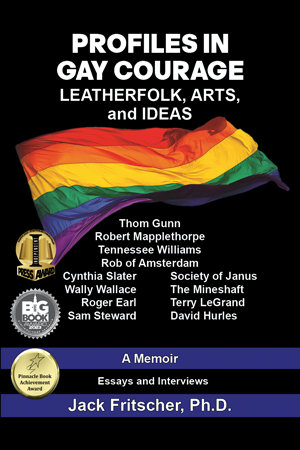

PROFILES IN GAY COURAGE

Leatherfolk, Arts, and Ideas

Volume 1

by Jack Fritscher, PhD

Also available in PDF and Flipbook

ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE

November 4, 1946-March 9, 1989

Fetishes, Faces, and Flowers of Evil

1

The pre-AIDS past of the 1970s has become a strange country. We lived life differently those many years ago. The High Time was in full swing. Liberation was in the air, and so were we, performing nightly our high-wire sex acts in a circus without nets. If we fell, we fell with splendor in the grass. That carnival, ended now, has no more memory than the remembrance we give it, and we give remembrance here.

In 1977, the Thursday before Halloween, Robert Mapplethorpe arrived unexpectedly at my job and in my life at 1730 Divisadero Street in San Francisco. I was editor-in-chief of the international leather magazine Drummer. Robert was a Downtown photographer struggling to be known above 14th Street and outside New York.

He had been lucky on January 6, 1973, when Tennyson Schad at the Light Gallery, 1018 Madison Avenue at 78th Street, took an Uptown chance with his first little show, a one-off, titled Polaroids. The invitation was a self-portrait of the photographer as a young man, his crotch shot in close-up, with his two hands holding a Polaroid camera just above his flaccid penis to make the radical equation that his cock was his camera and his camera was his cock.

* * * *

Street addresses, like Robert’s loft at 24 Bond Street in New York, are important in documenting gay history because they help mark the longitudes and latitudes of who’s who in class, custom, and gestalt — like the separation of Uptown, Midtown, and Downtown in Manhattan — in a gay culture whose pop-up gayborhoods, venues, and media are constantly rising, changing, gentrifying, moving on to the new, and forgetting the old. Addresses make possible the interactive fun of using Google Street View to check out locations where the past happened. It may be worth noting that fifteen or so years after Stonewall, “gay history” morphed into the hard-nosed “gay history business” in academia, museums, and publishing with the arrival of AIDS alongside the first sustainable gay book publishers and queer studies startups.

* * * *

2

On February 5, 1977, Robert debuted two landmark solo shows, his first foundational coming-out shows, each lasting ten days, both small, both Downtown in SoHo. In the never-ending schism over his work, Holly Solomon took a chance on his career promoting his Flowers and Portraits at her Holly Solomon Gallery, 392 West Broadway, while the Kitchen Gallery, 484 Broome Street, simultaneously opened with Erotic Pictures, his first leathermen and male nudes — which Holly had refused to hang.

In 1978, the schism over his duality continued even in liberal San Francisco when Edward DeCelle hung Robert’s erotic pictures in his 80 Langton Street gallery in the leather district South of Market Street, and Simon Lowinski hung his flowers and portraits in his chic antiseptic gallery north of Market Street at 228 Grant Avenue near Union Square. This schism influenced all his future shows. He did not score his first museum show until the year after we met. Drummer wanted good photos. Robert was experimenting with portraits of leathermen and urban-primitive scenes of leathersex. Always recruiting new models with kinky trips, he wanted access to the leather community of potential fans, models, and collectors who subscribed to Drummer which at that time had a monthly press run of 42,000 copies.

He arrived at my desk and unzipped his big black leather portfolio of photos perfectly suited to my goal to upgrade one of the first gay magazines founded after the Stonewall riot. He knew that one of the civilizing and virilizing things Drummer did was teach gay men new ways to live. I accepted every black-and-white photo and hired him to shoot a color cover for Drummer 24.

Our mutual professional desires ignited instantly into mutual personal passion. Imagine what it was like to reach inside Robert and feel his heart pumping against your fist. In movie scripts, couples meet cute in less intense ways. We became bicoastal lovers for nearly three years when our erotic love became like Whitman’s Calamus love between friends as he moved from white leathermen to black men, and I met marine botanist and film editor, Mark Hemry, the man who would become my husband for life. We knew what we were doing. We both liked ethical polyamory in our crowded love affairs. We weren’t kids. He was thirty-one, and I was thirty-eight.

Robert was a serious artist, disciplined enough to play by night and work by day. His “take” (one of his favorite words) on life pleased me. He was a grownup gifted with the discipline that drives talent. That made him appealing. During the wild post-Stonewall coming-out party of the 1970s, he was the opposite of well-intentioned writers, painters, and photographers who wanted to write, paint, and shoot, but instead spent their time in 24/7 fuckerie scoring a dozen tricks a day in the backrooms of gay bookstores, bars, and baths, or spent their cash on cannabis, cocaine, and Crisco. The sex and drugs that drained some, fueled him.

Robert Mapplethorpe’s bawdy life was the source of his art. He asked me to write about him. So I did in journals of notes and quotes. “You live it up to write it down,” he said. “I expose myself on film. We both have the Catholic need to sin and confess.” Handwritten letters and messages sealed our east-west romance. “Jack, if you’re not free for dinner tomorrow night, I’m going to beat you up. Love, Robert” (July 26, 1979). To Robert, S&M did not mean sadism and masochism so much as sex and magic.

Robert by the late-1970s was becoming a reciprocal talent in the New York art scene. He shot Warhol. Warhol shot him. He made Warhol look like a saint. Warhol made him look like a blur. In 1978, I introduced him to Tom of Finland. Robert shot Tom. Tom drew Robert. I took him to meet Thom Gunn. Robert shot Thom. Thom wrote the poem, “Song of the Camera,” for Robert. Whenever I pissed in Robert’s 24 Bond Street loft, I stood facing him, framed, hanging on the wall over his toilet, looking down, insouciant, from the black-and-white portrait Scavullo had lensed of him. Francesco caught Robert, hands jammed into his leather jeans, Kool cigarette hanging from his mouth, torn T-shirt tight around his speed-lean torso, his road-warrior hair tousled satyr-like. He confessed in our correspondence that his main enjoyment in sex was uncovering the devil in his partner. Lucifer, the Prince of Darkness, was avatar for Robert, the prince of darkrooms.

3

Robert, innocent as any victim, was killed by AIDS on March 9, 1989, at the pinnacle of his international photographic success. With his early S&M work first published underground in Drummer, he was an archetype of the homosexual artist who struggles up from the gaystream of outsider art to mainstream acceptance in galleries and museums.

At age sixteen, he made his first trip to Manhattan from Floral Park, Long Island, across the border from Queens, where he was born November 4, 1946, and baptized into the Catholicism that infused his art. He attended Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, joining the Army Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) and earning a BFA bachelor-of-fine arts degree while crafting jewelry and sniffing around the edges of photography, making mixed-media collages from other people’s photographs, until, in 1971, art historian John McKendry, curator of photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, gave Robert his first Polaroid camera to take his own photographs. McKendry fancied Robert, as did his wife, Maxime de la Falaise, the British fashion model, Vogue columnist, and Warhol actress who navigated Robert’s entrée into European and American high society into which he flowed like sparkling water seeking its own level.

Soon after in 1972, Robert was exhibiting at a small gallery in a group show when, he told me, his life abruptly changed the moment his first lover of three years, the elegant fashion model David Croland — who starred with him and Patti Smith in Sandy Daley’s Warholian underground film Robert Having His Nipple Pierced (1971) — introduced him to a man admiring his photos. The man took Robert’s hand and said, “I’m looking for someone to spoil.”

“You’ve found him,” Robert said.

The man was the charming, aristocratic millionaire Sam Wagstaff, the brother of Mrs. Thomas Jefferson IV, who in 1987 contested Sam’s will whose beneficiary was the dying Robert. Sam was a patron of the arts, who in the 1970s, came from self-imposed lay monasticism, with Robert in tow, to create a new fine-art market and intellectual respect for photography — including Robert’s photography whose esthetic of eros was endorsed by art experts, and acquitted by law a dozen years later in the culture war when seven of his pictures were put on trial for obscenity in Cincinnati in 1990. Robert became Sam’s protégé, lover, and friend. They were born on the same day, November 4, twenty-five years apart. Sam was fifty. Robert was half his age.

4

One splendid sunny March afternoon in 1978, after Robert and I had flown from San Francisco to Manhattan, we taxied directly to the restaurant, One Fifth, at 1 Fifth Avenue, with its deluxe ocean-liner decor, where Robert walked us through the maze of tables into an upholstered green banquette. Several people nodded and waved. Robert’s chiseled face, porcelain skin stretched tight over classic Celtic bone structure, broke into his easy grin. “I’m not into celebrities,” he once told a New York Times reporter.

Nevertheless, celebrities and socialite swans, introduced by de la Falaise and Croland, climbed the stairs to his fifth-floor Bond Street loft to sit in the south light of the front room with its silver umbrellas and exposed heating pipes — like the radiator gripped by the limber Patti Smith crouching naked, almost fetally, on the painted wood floor in his 1976 pictures of her. Whether in studio or on location, everyone from the 235-pound Arnold Schwarzenegger in a four-ounce Speedo to Princess Margaret drinking Beefeater Gin in Mustique wanted to be photographed by the fashionable bad boy with the Hasselblad.

“Arnold was cute,” Robert said. “He sat with all his clothes on and we talked. He’s nice. He’s bright. He’s straight. The gay bodybuilders I’ve been with are so roided out they’re like fucks from outer space. I can’t relate to all that mass. It overshadows personality.”

Robert’s relationship with bodybuilder Lisa Lyon was a seditious gender-spinning upgrade of the physique photography he found on 42nd Street in gay magazines like Physique Pictorial, The Young Physique, and Tomorrow’s Man. Lisa was the first of the new wave of female bodybuilders and Robert promoted her because she was, like him in his gender-fluid self-portraits, changing stereotypes into archetypes on the androgynous cutting edge. Lisa at our supper directly across the street from the Castro Theater at the clone café Without Reservation, 460 Castro, seemed yet one more psychic twin to Robert. She was his good-looking, poised, and charming collaborator.

The culturally predictable pin-up pictures of her in Playboy gain an edge because Robert’s transgressive photos of her subvert the “Playmate” cliché. In a related way in the Mapplethorpe universe, Robert’s pictures often explain one another like pieces in a meta-puzzle of his design. The Mapplethorpe photo of a calla lily hanging in an elegant condo dining room gains frisson from the Mapplethorpe fisting photo hanging in the bedroom.

I inhaled the atmosphere at the posh One Fifth. Robert lounged comfortably close, waiting for Sam. “Did you ever go to Max’s Kansas City?” Robert asked. “Did you ever have to go to Max’s Kansas City? I went to Max’s every night for a year. I had to. The people I needed to meet were there. I met them. They introduced me to their friends.”

Robert delighted in acting the cool edgy artist with clients, celebrities, and editors of magazines. Vogue rang us awake one morning. Was it Grace Mirabella, frequent publisher of Helmut Newton and Richard Avedon, begging Robert to shoot Faye or Fonda or Gere or Travolta or somebody hot they needed fast? I could hear only his side of the conversation, our bodies tucked spooned together, my front to his back, a fine fit, lying slugabed in his twisted sheets on his mattress on the floor.

“Ah, a principessa!” Robert said. Vogue wanted some princess, maybe some rising hot soon-to-be royal like Gloria von Thurn und Taxis headlined in the tabloids as “Princess TNT,” or anyone part of the stylish Eurotrash invading the New York club scene. The climbing Robert liked climbing the climbers. He had a soft spot for princesses and a hard-on for nasty sex.

While waiting to meet Sam at One Fifth, I realized what confidence Robert had pushing the activism of his queer art against the mainstream prejudice against homosexuality, and into prominence by identifying himself as a society photographer while assaulting mainstream conventions with phallic nudes and hydraulic leathermen. Yesterday, the kidnapped torture victim John Paul Getty III. Today, Elliott Siegal, the toughest S&M hustler I’d ever hired for the cover of Drummer. Tomorrow, Eva Amurri, the three-year-old daughter of Susan Sarandon.

In a decade of fashion designers like Saint Laurent and Halston and Vivienne Westwood democratizing their brands by sucking up the DNA of young street-smart punk styles, he sired the perfect frames of his layered signature look on the streetwise DNA of leathermen, fetish clothing, and chain-link jewelry — all de rigueur at bars, baths, and sex clubs like the Mineshaft.

Cinematically, in the genesis of gay popular culture, Robert was indelibly inspired by Kenneth Anger whose stunning rapid-fire frames in his 1963 montage film, Scorpio Rising, previewed to the teenage Robert the very leather bikers, S&M action, piss fetishes, film stars, occult rituals, Satanic costumes, machine guns, death’s-head skulls, and blasphemous Christian and Nazi images whose shock power — to the tune of black rock-and-roll on Anger’s soundtrack — he would soon source and morph into the static “queer cinema” of the single frames in his own narrative canon — where he very often framed several photos together à la Warhol’s Nine Jackies as if they were successive frames in a film strip from a private movie: Self-Portrait in 1972; Candy Darling in 1973; Charles and Jim, Kissing in 1974; Holly Solomon (Three Portraits) in 1976; and Jim & Tom, Sausalito in 1977.

5

With his nostalgie de la boue, his love of slumming which was pivotal to his art, Robert cross-pollinated the flowering divine decadence of Manhattan society with the sticky gay seed of the leatherman esthetic that captivated him in Times Square porn shops where 42nd Street became his teenage Road to Damascus.

In the conveniently archival adult bookstores, the boy from Queens was converted from a photographer into an artist who was a photographer when he divined the difference. A delicate distinction often lost on gays with cameras who wanted to be Mapplethorpe but were not artists. He changed the way he thought about developing his own esthetic when he discovered, in addition to Anger, the radical photography of homomasculine artists like Bob Mizer of AMG Studio, Chuck Renslow of Kris Studio, Don Whitman of Western Photography Guild, and Bruce of Los Angeles. At sixteen, he was a junior midnight cowboy coming out into an art tutorial he could only get on the pop-culture strip of the gloriously decadent 42nd Street.

Walking on the wild side of Warhol’s black-and-white movie portraits of faces shot close-up in Screen Tests, and cruising with the acumen of a street photographer, he assessed random faces and bodies he imagined he might upgrade from down-low Polaroid screen tests to formal studio shoots. He took up smoking. White men smoked Marlboros. He smoked Kools because black men preferred Kools.

On his own, he began collecting original photographs. To buy pictures for his cut-and-paste collages of other photographers’ work, he hustled. Like Caravaggio, he turned a trick or two.

Imagine if you could buy the one and only original Mapplethorpe offering himself on sale around Times Square for twenty bucks sulking cocky inside the Haymarket hustler bar, or nursing his “French Drip Coffee, 10¢,” eyeing the Johns over a “Tongue Sandwich with Lettuce and Relish and Potato Chips, 65¢,” at the Horn and Hardart Automat at 1557 Broadway.

He studiously spent snowy afternoons and hot humid evenings tramping 42nd Street searching and researching deeper into dozens of dirty book stores. He fingered his chewed nails through thousands of wooden filing bins of a million gay photographs in mint condition selling at ten cents each. Nothing grabs a viewer like sex. Sex seduces. He told me he preferred “intelligent sex.” He wanted his elegant pictures to excite viewers’ brains and bodies the exact way that porno succeeds because its interactive power causes brain and body responses that pleasure the viewer.

6

Across the crowded room, Sam Wagstaff entered, making his modest way through tables of celebrities, blue-haired ladies, and out-of-towners. His handsome granite face was eager for Robert who introduced us before they touched. They were too cool to more than air kiss in public. When Sam held out his hand, Robert pulled back in surprise at the diamond ring Sam slipped into his palm. “Welcome back,” Sam said. Robert, swear to God, bit the diamond with his teeth. I nearly died. To Robert, who fancied himself an imp of the perverse, nothing was sacred.

Sam laughed, and after lunch whisked us into the building’s one elevator, up past his 8th-floor apartment devoted to his photo archive, up to the 27th floor where he lived in his all-white penthouse atop One Fifth. His zillionaire digs were Spartan, but what was there had all the comforts of old money, good taste, and safe home. Historical photographs of all kinds lay shuffled about like playing cards stacked in casual treasure piles on the white tile floor. Robert’s interest in photography had kindled Sam’s. Inspired by Alfred Stieglitz’s push to include photography as a fine art, they had bought up — and cornered the market on — the best of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century photography, including male nudes and physique photography shot in the covert homoerotic style of the times.

The past in that present met the future. Sam and Robert built up a keen-eyed blue-chip collection of early photography that we three carefully handed back and forth, including sepia-toned photographs of Native Americans shot by the white Edward S. Curtis whose own millionaire patron was J. P. Morgan. Robert studied his way through thousands of photographs, exactly the way he had self-educated himself in the commercial porn archives on 42nd Street. He absorbed the history of content, style, and ethnography and folded it into his images of race and gender and sadomasochism, several of which saw first publication in my 1978 Son of Drummer feature article “The Robert Mapplethorpe Gallery (Censored).” In 2016, that Drummer issue, laid open to that feature article, was displayed as an art object itself in a glass case at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art linking its Mapplethorpe exhibit to the simultaneous Mapplethorpe exhibit at the Getty.

That Drummer article, which I opened with the shaved skull of Cedric, N.Y.C., was intended as trial-balloon publicity for his X Portfolio. Robert was obsessed with skulls: Skull and Crossbones, 1983; Ken Moody and Robert Sherman, 1984; human Skull, 1988; and Skull Walking Cane, 1988. The four-page feature introduced to the national media culture of leatherfolk his transgressive pictures of bondage; black rubber body suits; a nude male self-mutilating cutter with torso scarified by razor blades; a leather master standing with a leather slave seated in chains in a designer apartment (Brian Ridley and Lyle Heeter); men sucking piss-dripping jockstraps (Jim and Tom, Sausalito); men with fists up their butts; and a celebrity leatherman, Nick Bienes (Nick), with a Satanic tattoo on his forehead.

When I met Nick in 1972, he lived in a tiny apartment decorated like a subway car with rubber mats on the floor, and several black-and-white video monitors inserted like small subway windows into the walls papered metallic gray with tinfoil. Under his pseudonym “Judith Gould,” Nick wrote a sensational bestseller that became the Joan Collins’ TV mini-series, Sins. Robert photographed him specifically for a Drummer cover that never came to pass.

“You could do the same,” Robert said. “Write a mini-series. Make some money.”

Robert was as well acquainted with the English and American smart set as he was with after-hours sex clubs like the Mineshaft where he was the official photographer, shooting pictures like his 1979 portrait of leatherman David O’Brien, Mr. Mineshaft. As self-dramatized in Robert Having His Nipple Pierced, he liked consensual, ritual, sexual action that philistines mistake as violence. He gloried in human flesh and courted statuesque male and female dancers and bodybuilders who were athletes of the kind who were artists sculpting themselves.

His taste ran from perversatile leathermen to finger-licking freaks to majestic blacks. His time as a junior cadet marching in his ROTC uniform during the controversial Vietnam War, that dragged on until 1975, alerted him to the cultural fetishes around the American flag and American guns. The Sixties hippie he was, who could be simultaneously traditional and subversive, photographed both flag and guns, as well as warships like the aircraft carrier Coral Sea, to exploit the extra bonus of their patriotic sales appeal. During the mid-decade when Bicentennial fever was sweeping the country merchandising Americana collectibles, he shot his tattered American Flag in 1977, followed by a second flag in 1987. In both, he digested the red, white, and blue in black and white.

7

In the sweet polyamory of 1980, wanting my San Francisco lover Jim Enger, a most handsome championship bodybuilder and one of the most sought-after men of the 1970s, to be preserved forever in all his transitory muscle glory by the permanence of my New York lover’s camera, I set up a shoot on March 25, in a Twin Peaks condo perched high above Castro Street, that we three ultimately found satisfying even though it was upended by Robert’s pique at Enger’s not-unreasonable refusal to sign a release without photo approval.

Standing between my two lovers, I saw what happens to a good deed when egos collide. The handsome blond champion bodybuilder with his many first-place physique trophies thought he was the star of the shoot. The dark photographer working with the power tool of his camera thought that he was the star. Even so, we three, ever so cool, shot the shoot and went like athletes who compete on the field and bond in the pub, out to another supper with Lisa Lyon.

Afterwards, she and Robert and Jim and I took a cab together to the opening of his show at the Lawson DeCelle Gallery where gay society photographer Rink captured all of us together in the same frame chatting with the anthropological photographer, Greg Day.

The civil rights activist Day had been Enger’s roommate in college before Day migrated to New York and documented his own 1970s “take” on leathermen, Warhol superstars, and the gutter art of “genderqueer” performance artist Steven Varble.

Months later, in his Bond street darkroom, Robert cut off Jim’s head and re-framed one of the gorgeous V-shaped nude rear-torso photos into a headless full-color greeting card sold in gift shops in Provincetown.

In early 1978, Robert suggested we do a book together. He copied me with fifty photographs of some of his most edgy work so I might write the introduction to our book, Rimshots, pairing his erotic pictures and my erotic writing. As happened at that pressurized time of competing representations by galleries, and of the censorship wars caused by Anita Bryant, our venture fell through because of New York reasons, and some of those deep dark photos have yet see the light of day as have his once forbidden fisting photos. The proposal manuscript for Rimshots is housed at the Getty Museum Research Institute which in 2011 the Mapplethorpe Foundation made the official archive of his work.

In 1983, Robert had curator Edward DeCelle hand-deliver to me a package whose personal value far exceeds offers asking me about buying rumored “private images” Robert might have given me for safekeeping. In 1978, DeCelle had displayed several of the same Mapplethorpe photos I had printed simultaneously in Son of Drummer in his Censored exhibit — which Robert and I helped him hang — at his Lawson DeCelle Gallery, 80 Langton Street, San Francisco.

At that time, DeCelle introduced Robert to San Francisco high-society blue bloods like Gordon and Ann Getty; Judge William Newsom, the Getty lawyer and environmentalist who was related by marriage to Nancy Pelosi, and was the father of future mayor and governor Gavin Newsom; and the regal Katherine Cebrian. At the same time, I introduced him to underground socialites in the alt-world leather salon around Drummer. In DeCelle’s delivery, Robert gave me, in gratitude for the Enger shoot, two stunning silver-gelatin prints of Jim — one with face. Robert is likely laughing at my sentiment against selling his work; but some things, Roberto, have no price.

In 1986, just as his AIDS was diagnosed, eight of Robert’s pictures managed to dominate and vivify Rimbaud’s text in a luxe quarto version of A Season in Hell. He pictured himself on the cover as the pagan Pan, the horned devil out for a Mapplethorpe dance around the bacchanalian Maypole.

One of his most expressionistic role-playing frames is his contorted Self-Portrait with Whip (1978). In this campy comic photograph about pulling art out of your ass, his butt cheeks framed in leather chaps dramatize S&M penetration and scatology with the bullwhip handle inserted petulantly up his skinny bum — its long tail, evacuating turd-like down its full braided length, and trailing out the bottom of frame. This polite shit picture showing a snarling rugged look on his otherwise sensitive face is remarkable autobiography because in it the artist who never wrote a monograph about his process reveals his challenging attitude and agency in front of and behind the camera by showing the cable-release bulb in the fuck-you fingers of his left hand.

8

“This is,” I told him our first night together in 1977, “your first reincarnation in three thousand years.”

“How so?”

“Intuition. I get re-incarnational readings off some people.”

“I’m one?”

“The most intense.”

The world and Robert Mapplethorpe were on no uncertain terms with each other. In his New York incarnation, or in past goat-footed Dionysian lives, Robert demanded, managed, and delivered what he wanted from life. He lived on an ascending arc of creativity, ambition, and success. He died with seven books in print; a large bibliography of critics and social historians appraising him, not the least of whom was Susan Sontag who wrote the introduction to his portrait book, Certain People; a top-tier list of more than one hundred international gallery exhibitions, the triumphant epitome of which was the successful showing at the Whitney Museum of American Art from July 28 to October 23, 1988, which Robert gallantly attended in a wheelchair and an oxygen mask.

Like Jesus taken to the mountaintop by Satan who promised all the kingdoms of the world and their glories, the dying Catholic Robert Mapplethorpe if taken to the top of the Empire State Building could have ascended to heaven looking down on the city he conquered. He was a definitive New Yorker. In 2016, poet and theorist Kenneth Goldsmith in his comprehensive book Capital: New York, Capital of the 20th Century presented Robert as “the Ultimate New Yorker of the 20th Century” in his chapter written by Patti Smith, Patricia Morrisroe, and me.

Robert took from life all he wanted of its quality, if not of its longevity. He lived fast romancing the 1970s pop-culture paradigm of Byron, Shelley, and Keats who died young like James Dean, Janis Joplin, and Jim Morrison, whom he most resembled in look and style. Rimbaud died of cancer at thirty-seven. Robert died at forty-two, the same age as the androgynous Elvis who had also turned to black culture for inspiration.

Among all the apocalyptic photos giving absolutely necessary personal faces to the genocide of AIDS, one of the most appalling photographs is Jonathan Becker’s photo of an emaciated Robert Mapplethorpe attending his Whitney opening. AIDS is a time-lapse speed trip of the aging process. Robert looks a million years old in the stark realism of Becker’s candid news photo illustrating Dominick Dunne’s essay, “Robert Mapplethorpe’s Proud Finale,” in Vanity Fair, February 1989.

The year before, Robert the formalist — assisted by his dedicated brother Edward Maxey Mapplethorpe, himself a noted photographer — had shot the perfect moment of his mortality in his Self-Portrait with Skull Cane wherein Edward, assisted by Brian English, makes Robert’s ghostly head float disembodied, with the death mask of his face fading in soft focus in the upper right on a field of black, while in the lower left field his right hand in crisp focus holds the cane topped with a skull. The penitential choice of the skull makes death his subject the way the choice of one of his lilies in his hand could have made resurrection his point. Soon after the stark salute of this “morituri” photo, Robert, who wore the Roman torture device of a cross on a chain around his neck, returned to Catholicism.

Predicting his short life, I wrote about Robert in my 1978 short story that was republished in the 1984 anthology, Corporal in Charge of Taking Care of Captain O’Malley, that Robert, “forever reincarnating, will, when his next death-passage is appropriate, take his life with the same hands with which he has created and crafted it. He will neatly, stylishly even, finish it.” Dunne and Becker confirmed Robert’s stylishness right down to that insouciant death’s-head skull cane that was his final prop in his final self-portrait.

9

Robert’s early work, sexually explicit leather images, many of them shot in his hidden life in San Francisco, shocked the New York art world in the 1970s. His was an assault with a deadly camera. What succeeds better than calling society’s bluff? He double-dared squeamish clients: “If you don’t like this photo, maybe you’re not as avant-garde as you think.”

His reputation spread beyond Manhattan chatter of a new talent in SoHo. The bad boy had tuxedo elegance and leather attitude. His ironic smile charmed the cold cash from the checkbooks of clients, patrons, and gallery mavens. At $2,000 a shoot, the right people sat in Robert’s studio. The right runs of platinum prints and lithographs, dispensed in wallet-whetting limited editions, found their way into the right galleries, the right magazines, the right addresses.

Robert was a new shooting star, a lone rider, a nova-bright guy in the fast lane, careening with me, one October night, up 6th Avenue, both of us happily stoned on pot, but less loaded than the wild Travis Bickle taxi driver who, driving quite recklessly, scared us both so much we crouched cuddled on the floor of the backseat.

He sometimes acted out what he wanted me to see. He wanted intimate biography. Although he rarely read books, he admired the publication of books and courted writers who could be his eyewitnesses. He liked that this tenured university professor had already written three books on subjects he could relate to: a dissertation on Tennessee Williams, a leather novel, and a university-press book on the occult featuring the High Priest founder of the Church of Satan Anton LaVey whom, like Tennessee Williams, he should have photographed. “You do write well,” he wrote me on April 20, 1978, “I think we should go fast on the book [Rimshots].”

He confessed, late one night, walking elbow to elbow from our signature haunt, the Mineshaft, that, as a starving student at Pratt, he had depended on the survivalist Patti to live. Patti became Robert’s first patron the day she went to work to earn money to support him. She was a hyphenate poet-singer-artist who in tandem with Robert set out to score the soundtrack of their fifteen minutes of fame. The photogenic waifs stylized their androgynous Jack-and-Jill look while each entertained other lovers. Building on pop culture, they conjured their new identities as artists in the flophouse drug den of the Chelsea Hotel. Robert said that Andy Warhol’s 1966 film, Chelsea Girls, inspired him to move to New York in 1969.

During the free-wheeling open-access of the swinging 1960s and 1970s, more than one handsome young man walked into gay venues like Warhol’s Factory and was hired immediately on the cheap. Teenage juvenile delinquent Joe Dallesandro met Andy in 1967 and became a Superstar. The teenage artist Jed Johnson, delivering a message in 1967, was hired as a janitor, and became Warhol’s lover. At the same time, Robert scored first blood and respect when he became a staff photographer for Warhol’s Interview magazine.

Wherever doors were open, in walked Robert. By 1971, Robert was tête-à-tête with the Catholic Bob Colacello, the platonic-ideal of an editor at Interview. By 1972, when David Croland introduced him to Sam Wagstaff, Robert may have needed Sam emotionally in the world of polyamory to cope with Patti’s romance with cowboy-playwright Sam Shepard. There were two Sam’s in their relationship. Years later she told FarOutMag in 2020 what the gay Robert, who was not a jealous man, may have sensed about the straight Shepard in 1971: “…We [Sam and I] had an equal but masculine/feminine relationship…it was like having a man in my life.”

With Shepard, Patti co-wrote and co-starred in their play Cowboy Mouth, a one-act about their affair in which a rockstar woman kidnaps a man she holds at gunpoint in a motel where he claims she ruined his life while begging her to tell him stories about Rimbaud and Verlaine. It opened and closed like a subway door at the American Place Theatre in Midtown Manhattan in April 1971. After opening night, Shepard reportedly fled New York while Patti, staying forever friends with him, headed back Downtown. After Hilly Kristal opened CBGB at 315 Bowery Street in 1973, she became one of the first female punk rockers in a CBGB roster that included singer-composer-poet Camille O’Grady and her band Leather Secrets.

Just before Patti retired from public view and left New York for Detroit in 1979 to marry rocker Fred (Sonic) Smith, Camille and her punk boys performed at the Mineshaft, as documented in French director Jacques Scandelari’s 1978 film, New York Inferno, scripted by my playmate and friend, Village Voice film critic Elliott Stein. O’Grady, who in 1978 paired up in San Francisco with Robert Opel who had wowed a billion people when he streaked the live 1974 Academy Awards telecast, said she had also dated Robert in 1970s New York. In my video interview of Camille, she said she always referred to her rival Smith as “Ms. Myth.” Patti’s music and Robert’s gender-bending simpatico cover portrait of her channeling “Frank Sinatra ‘cool’” for the Patti Smith Group album Horses was a trophy to their bond. With Sam’s money, Robert had earlier funded an indie record label, Mer, to self-publish and release Patti Smith’s first single.

“Patti,” Robert told me, “is a genius. She deserves to be a legend.” He who was no sexist Pygmalion said it proudly when he screened for me Still Moving, the new thirteen-minute black-and-white film he had directed and shot of Patti who was her own parthenogenetic person — and no man’s Galatea.

10

Robert was a legend in his own time. Mapplethorpe! His name — which he demanded his photographer brother not use professionally — acquired mystique, and entered popular culture as a meme. It’s twice been an answer on the game show Jeopardy, a punchline in the film comedy The Bird Cage (1996), and a “security password” in Season 1, Episode 7 of the Canadian sci-fi series Dark Matter (2015). Under Sam’s guidance and through the Robert Miller Gallery, 524 W. 26th Street, limited prints of branded Mapplethorpe photographs zoomed up in price, a sure sign of success in America where money is the way of keeping score. His New Orleans mentor, the painter and photographer George Dureau, told me on videotape shortly after Robert’s death: “Robert ran himself like a department store.”

Robert’s opening at Robert Miller in 1978, in which his pictures hung alongside Patti’s drawings, was marketed to capture a diverse demographic of suits, pearls, black leather, and New Wave punk. In 1981, a Mapplethorpe sold for $2,000; in 1984, $5,000; in 1987, $15,000; in 2017, his portrait of Milton Moore, Man in a Polyester Suit, one of the most recognizable photos in the world, sold for nearly $500,000. When Sam died of AIDS in 1986, he willed Robert, whom he truly loved, $5,000,000. Because Warhol died a short two years before Robert, there has been a postmortem competition in the press between the two rival estates as to which is worth more. Artists all die, but their estates go on forever because that’s where the money is.

By 1987, Robert’s name and face were so commercial a commodity the handsome devil posed with fashion photographer Norman Parkinson in a campy full-page ad for Rose’s Lime Juice shot for the May issue of Vanity Fair by Annie Leibovitz whom Robert had in turn lensed earlier wearing a leather jacket in 1983. What a send-up for a man whose favorite cocktail was poppers and MDA.

Beginning with Drummer in 1978, his photographs slowly began to grace the covers of other alternative magazines like New York Rocker and East Village Eye. By January 1988, at the height of the AIDS crisis, American Photographer featured a Mapplethorpe cover photo and lead story “Mapplethorpe: The Art of His Wicked, Wicked Ways.” The June 1988 Harper’s published some of his photos of blacks in Shelby Steele’s lead essay, “I’m Black, You’re White, Who’s Innocent: Race and Power in an Era of Shame.”

By 1989, he had worked, not clawed, his meritorious way up to the pop-culture pinnacle of the cover of Time magazine with his portrait of AIDS hero U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, shot just thirty-seven valiant days before Robert died. Moralizing critics might autocorrect and remember it was not ambition that killed him. He was killed by a virus.

11

Late one morning, he sat me down in his Bond Street loft. An amusing redundancy of sex and religion was in the seasonal air for leathermen raised as altar boys with a taste for erotic blasphemy. It was Catholic Holy Week from Palm Sunday to Easter, March 24, 1978. Each day of this ritual Passion Week was a scene in the unfolding S&M drama of a male-male kiss leading to Roman soldiers capturing, stripping, mocking, binding, whipping, crucifying, and stabbing the bearded athletic Christ who was mummified in total bondage and closeted in a tomb from which he escaped. Like a night at the Church of the Mineshaft. Truth be told, Robert and I didn’t create out of our Catholicism as much as we created out of our PTSD from Catholicism. The sun slanted through the four south-facing windows and hurt my eyes. We had kept each other going for days. It may have been Wednesday before Good Friday.

“You okay?” He unscrewed the legs of his tripod.

“Yeah.” There was a fire escape outside the windows.

“Come on, Jack, you’re lying.”

“How embarrassed do you want me?” We were perversatile together, but while he set up his gear, I shied away.

“Why should you be embarrassed?”

“I don’t know why.”

But I knew why. Robert’s eye was true. The third eye of his camera proved it. I understood why primitive cultures feared that the camera stole their souls, but maybe he was trying to save my soul, or at least examine it out of curiosity. He always wanted everyone to go farther than far out. He wrote to me on May 21, 1978, “I want to see the devil in us all.” We both played at being cynics abroad in the world, but back up, buddy. As a journalist, I may have written a book on popular witchcraft, but I was no Faust like he was. Maybe he wasn’t playing. Even though I frequently traveled for extended cultural sex-tourist stays in New York beginning in 1957 when he was eleven, maybe I was only California attitude. Maybe he was existential reality.

Helping found the American Popular Culture Association in 1968, I had academic purpose, and loved immersing myself in the gay underground of New York in the 1960s when he was in school. While neither of us was present in Greenwich Village the night of the Stonewall riot in June 1969, I did march in May 1970 alongside the newly founded New York Gay Liberation Front protesting the U.S. bombing of Cambodia which I shot on Super-8 film that can be seen under the opening titles of Todd Verow’s 2021 film, Goodbye Seventies. Robert never covered live events, not even candid shots at the Mineshaft. He was a formal studio photographer who did not like to shoot from the hip.

So, I sat in his studio, the visiting West Coast writer, submitting to the East Coast photographer’s camera eye that made me anxious about appearance and reality. His sight and insight cut through bull. In conversations, we traded quips for fun, but now he was dead serious. He was a man at work, assessing me, his hands arranging me, re-arranging me, deconstructing me frame by Duchamp frame, his Irish green eyes darting between me and his viewfinder. I remembered the first night we made love he licked his tongue across my eyeball. That homosurreality was a probing first. No one had ever so literally fucked my vision. Sitting for him in his sunny studio, I feared his eye, malocchio, his evil eye, his wonderful eye that through the omniscient third eye of his lens might burn through my appearance to my reality and tell me something I needed to know.

I had seen others whom he had photographed. Each person seemed different from the visage he captured in a single frame. I did not want to be victim of a single shot. Not JFK shot in a Zapruder 8-mm frame. I wanted to be Mapplethorped, transformed, if not into an exotic persona, then at least into the guise he fancied for gay writers the way he staged and shot Allen Ginsberg in the lotus position; Truman Capote barefoot in a chair; William Burroughs standing with a rifle; and Fran Lebowitz holding a cigarette. So my fear of his camera was primitive. He was a sorcerer. I surrendered to a magic process that X-rays a person in a single frame as a negative and then as a positive. I wanted to give the devil his due. I wanted him to have his way with my face.

Appearing nightly in the performance art that was his bed was not enough. Pillow talk was not enough. We were both tactical. I wanted what he wanted: to experience him working so I could write what it felt like to be objectified inside his process. Yet, for all my personal trust in him, I feared he might find the private face I thought I hid from the world. Photographs say what is true despite the sitter’s wishes.

Lebowitz, who is an influencer, said she made a big mistake in 1979 when she, who admits she’s hard to please, petulantly threw a dozen of the photos Robert had given her into the trash because, she said, he was “a rich man’s toy,” and she preferred his competitor, photographer Peter Hujar. Robert’s work always provoked reactions. Edward DeCelle told me Robert’s San Francisco portraits of my friend, Cynthia Slater, the leatherwoman co-founder of the BDSM Society of Janus, were “mercilessly harsh.”

In fact, Robert shot me effortlessly and quickly. He sealed the rolls of film and handed them to his assistant working in the darkroom in his loft. Because he had little interest in the hands-on process of printing beyond some editing and tweaking, he hired various assistants like his brother Edward, and Tom Baril who became his master printer.

Years later, when Sam bought him a luxury apartment at 35 West 23rd Street, Robert kept his 24 Bond Street man-cave into which he had moved in 1972 and kept unchanged, like his “Rosebud,” until the day he died. He loved the storied art and jazz music provenance of the building once owned and rented to artists by the painter Virginia Admiral who was Robert DeNiro’s mother. His funky Bond Street loft — not his designer and cocktail-party showplace on West 23rd where the BBC interviewed him — was always his safe home where his brother helped him shoot his final-exit selfie, a kind of Alas-Poor-Yorick Self-Portrait with Skull Cane (1988).

“The contact proofs will be ready tomorrow.” He hugged me.

I made us instant coffee in the jumble of his tiny kitchen. Under his framed silver screenprint of Warhol’s Jacqueline Kennedy in the pillbox hat she wore in Dallas, an ashtray broke from smolder to blaze on the table littered with Con Edison electricity receipts and please-please-please letters from galleries. Robert brushed the small fire from his discarded Kool to the floor and stomped the flames with his black pointy-toed snakeskin cowboy boots.

12

Minor disasters stalked us: that insane Saturday-night kamikaze ride in the taxi up 6th Avenue; a car crashing into a corner diner spilling lunch-counter donuts all around us; a run-in with organized Italian businessmen; a young gay man shot in the shin, before our eyes, by a mugger in the lobby of 2 Charlton Street; a naked man falling headfirst out of a piss-filled bathtub to the concrete floor of the Mineshaft. It was dangerous, dirty, and divinely decadent New York in the 1970s still vivid on screen in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver and William Friedkin’s two films, The French Connection and Cruising, a gay detective story of leathersex S&M murders.

Robert laughed at my concern over the fire in the ashtray. “You’re paranoid,” he said.

“Signs and omens are everywhere.”

“Homosexuality can cause paranoia.”

“Homosexuals have reason to be paranoid.”

I thought of our friend and mutual model, Larry Hunt, whom I had photographed outdoors in bondage for Drummer during the 1977 Satyrs Motorcycle Club bike run at Badger Flat in the California foothills. Robert had photographed Larry the same year indoors in New York sitting on his Mission couch, feet and legs laced up tight to the knees in leather logging boots. That was Robert’s first and only photo exhibited in Robert Opel’s pioneering Fey-Way Gallery at 1287 Howard Street in San Francisco’s leather district SOMA on March 23, 1979, four months before Opel was shot to death in his gallery.

At the opening, Opel, mixing media with an S&M “Happening,” exhibited everyone’s favorite masochist, the sexy and fun Larry Hunt himself, live and in person in a cage near Robert’s photo, titled Larry Hunt: Boots and Bench (1977). Because Robert had decided on a whim, and too late for printing, his name was not listed on Fey-Way’s First Anniversary invitation, and is omitted from listings of his more proper exhibits. When Larry Hunt disappeared from a Los Angeles leather bar during the winter of 1981-1982, all that was found of him years later were his lower jaw and teeth in Griffith Park. There were rumors of a Mapplethorpe Curse.

I remember Robert lowered his eyes at my mention of paranoia. His mouth grew tighter. Robert resented resistance. Robert loved compliance. Shit happens, same as magic. Wordlessly.

We walked a silent fifteen minutes to Jack McNenny’s flower shop, Gifts of Nature, at 251 6th Avenue and Houston. It was not the first or only afternoon he and I hung out there. Robert was as famous for his subliminally sexy flower photographs as he was for his threatening pars pro toto phallic fetish pictures such as Mr. 10½ and Man in Polyester Suit in which the thick uncut black penis of his unrequited lover, Milton Moore — whom he presented headless in this 1980 photo at the same time he decapitated Jim Enger — droops succulently like a pollen-wet reproductive organ of a flower from the unzipped fly. Were Robert’s worshipful pictures of black men racist or racial? His derring-do in an age of civil rights encouraged people to think about larger questions around race, ethnicity, and sexuality.

The sweet Jack McNenny, the Irish-American floral designer with the drop-dead breath of an outhouse, always saved Robert his filthiest jockstraps and his best blooms for Robert’s Baudelairean Fleurs du mal. The name of Jack’s shop where he lived upstairs was a scatalogical pun. For a moment, the altar boy in me recoiled.

Jack was swamped with local orders for his handmade Easter bouquets. He was a character, and the neighborhood, except for the Mafia, loved him — but that’s another story of life compressed into docudrama. Four years earlier he had walked into Doc Siva’s corner pharmacy and announced to the proprietor of thirty-eight years that his store ought to become a flower shop. While Siva watched, stunned, McNenny removed the suppository display from the corner window and replaced it with a philodendron Doc had behind his counter. The plastic bust of the provocative Clairol Lady (“Does she or doesn’t she? Hair Color So Natural Only Her Hairdresser Knows For Sure”) gave way to an over-watered Swedish ivy. He got the shop on one condition. He promised to maintain the 1930s wooden cabinets, the frosted glass panels, and the marble floor.

As I had on other occasions when as a writer I wanted to experience what it felt like to have a hands-on creative job in New York, I picked up a florist knife to help trim stem ends from tulips and baby’s breath. All his bouquets were bespoke art; he could not bear commercial arrangements. Robert sat among the pots of Easter lilies, smoking on a high wooden stool near Jack’s brightly lit floral cooler. He was reading my vibe, suddenly, intuitively, knowing from my eyes I did not want to go to bed with him. Not that night. Maybe not anymore. Definitely not just then. He wanted to know why. I didn’t know why. I think it was because the devil had touched my soul with his magic camera.

13

Robert was miffed but congenial that afternoon when I stepped back in that moment just as the gay orgy of the 1970s, launched at Stonewall, was rocketing to its awe-inspiring zenith. Not since Rome. Not since Weimar. I wanted some neutral time together to sort things out. He wanted time to further his seduction. He suggested supper at Duff’s, 115 Christopher Street, where we lingered long and late over pasta and coffee. He plied beautifully subtle ways to untangle my mood. For some reason, he wanted me, not in any way forever, just for that night of the afternoon he had shot me.

“There’s been a madness on us all for some time,” I said. Like a good and proper gay man quoting books and movies, I was channeling Sarah Woodruff standing windswept on a dangerous sea wall in John Fowles’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman. Like her, I was faced with three different endings to my postmodern story. I knew Robert kept a copy of Fowle’s The Magus on his bookshelf, and hoped he could relate.

“You’re afraid to go as far into nasty sex as I want to take you.”

The hanging green-glass lampshades in Duff’s lit pools of light over separate tables.

“You want to be dirty.” He spun his web.

“Let’s pay the check.”

At the door, the cold spring night chilled straight through our leather jackets. Robert headed out onto the crowded midnight sidewalk. A hundred guys cruised slowly up and down the block loitering outside Ty’s Bar, 114 Christopher, and the Boots & Saddle bar, 76 Christopher. Feeling our musical comedy was turning into a disaster movie, I kept pace past the bagel shop we liked — that had been the Mafia-owned Stonewall Inn, 51-53 Christopher — all the way to Sheridan Square. The drama was coming right on cue. Across the street from the bright red signs of the landmark Village Cigars shop, we stood on the dark curbing a long time, not talking, stoned on grass, two still points in the rushing headlights and clamor of cabs and cars honking and streaming past us down 7th Avenue.

Finally, Robert said, “It’s stupid.”

“Everything is.”

“It’s stupid.” He wasn’t even holding one of his usual Kools to punctuate his gesture. “I’m not in love with you.”

“I never thought you were.”

“But when two intelligent people make love, if they don’t do it when they can, it’s stupid.”

“That’s it?”

“That’s that.”

This sexual short circuit was about the fuck of intellect?

He hailed a taxi. No hands on each other’s knees now. Where was that curious lesbian photographer, Nita? Whatever became of Nita? Earlier that week, she had shot us together when she discovered us sitting in painter Lou Weingarten’s new Stompers Gallery and Boot Shop, 259 West 4th Street, where Lou exhibited Tom of Finland, Dom “Etienne” Orejudos of Chicago, and Don “Domino” Merrick of New York. She was shooting a book on gay couples, and she liked the way our arms and legs wrapped around each other. We gave her the poses she wanted which were so like the dozen selfie poses Robert shot of us lounging affectionately together sharing a joint on his Mission couch.

She was right. Our bodies were a perfect fit. Our heads were another matter.

I ordered the cab to go to the Mineshaft.

“You need fresh meat,” the devil said.

In the Meatpacking District, the cab pulled over at 835 Washington, and into a street-life painting by William Hogarth. Leathermen uniformed in black-leather assless chaps, codpieces, and jackets stood in the shadows smoking outside the club’s metal door on the loading dock shared with a hundred burly meatpackers in bloody white butcher aprons, yelling, unloading trucks, shouldering huge sides of raw beef striated with fat into the florescent abattoirs, hanging long halves of cow bodies on overhead conveyor lines of meat hooks, ready for processing. Just like the sex action next door.

I pushed a twenty-dollar bill for cab fare between Robert’s clenched fist and his leather-chapped thigh. I turned full face to his, and the rhythm spilled out: “What you said you’re not, I think I partly am.” I meant “in love.” I climbed out, closed the door, and walked off without looking back. Inside the Mineshaft, a man could control the organ grinders.

14

Two mornings later, lying in bed with Robert in his loft, I felt his arm wrap around my neck. We were both repentant.

“What I said the other night,” he whispered, “I didn’t mean.”

I kissed his long artist’s fingers. I said nothing. I didn’t need to.

“I wanted to get really crazy. I want to go so far with you. Get so nasty.”

“This is my farewell tour to New York. I’m joining a monastery. This is it for sex.”

“Yeah. Sure.” He pulled from his leather jeans pocket one of those little plastic MDA bags he was always dipping his finger into and shoving up noses.

“No. I mean it, Robert. I’m tired of fistfuckers and dirty people. I’m tired of everybody always being sick with hepatitis and amebiasis and clap and crabs and you name it. You can glamorize sex all you want with your pictures. I can glamorize it with my writing. When did gay sex become a constant search for new ways to be disgusting.”

“You’re dirty, Jack. You have a face that could have been drawn by Rex. You have dirty eyes.”

“What I may want to do is not what I ought to do,” I said. “What about my eyes?”

“You’ve got dark circles.”

“I won’t after two weeks of rest. I’m not kidding. I’m heading back to California. I’m doing my own private version of being born again.”

“Dark circles are what I look for. Interesting people have dark circles.”

“Robert Mapplethorpe’s famous raccoon effect.”

“Stay through the week. It’s still spring break. Andy’s throwing an Oscar party at Studio 54.” The Academy Awards that year were April 3. “I have to go.”

“Don’t tempt me.”

“Mario Amaya will be there.”

I hesitated. I liked Mario. He was an art critic and a longtime friend. I had felt sorry for him when he had been shot, wounded, along with Warhol, when separatist feminist Valerie Solanas, the schizophrenic founder of SCUM (Society to Cut Up Men), had opened fire on Warhol for, she screamed, taking too much control of her life. Maybe Valerie, who died a year before Robert, felt about Andy the way I feared Robert’s pushing us beyond my common sense.

“Hard sex,” I said, “leads to hard times.” None of us knew then that gay liberation would soon play out its next act in an intensive care unit.

15

That lovely morning, I could have gone his way or mine. Were our night ships linked in convoy for so long never to connect again? If so, then I knew that what-was must remain always so dear to my heart and my head. We rarely dared say “love.” We had no need. Life is a series of Gatsby’s beautiful gestures: a look, a lick across the eye, a touch, a word, sex verging on love — each and all again.

Leaving on a jet plane, I fled the island of Manhattan for the peninsula of San Francisco. “I want, I need, I love, yes, love, with incredible respect, this man, Robert Mapplethorpe,” I wrote at twenty-five thousand feet in my journal, “even though we may never really be together again.”

When Robert sent me a package with a print of his photo of me, or perhaps not-me, or, more, what I was then, I hesitated. I wanted to see what my visionary bicoastal lover had found in me with his scrying lens. I had to see if I looked dirty, not from the inside out, but from the outside in. I had to know if I had a gay face: the haunted, hunted, distorted, stereotypical kind of the balding crewcut leatherman with a big brush moustache.

I had to find if my face had become like the Otto Dix faces in the opening scene of Cabaret, or like the Fellini Satyricon faces emerging in the bars and the baths and the Mineshaft: a dead giveaway of whatever vampyr night hunger it was that made us terminally different from other men. Had Robert exposed my soul to save it? Was this beautiful picture I treasure another “harsh” photograph like Cynthia Slater’s? Was this a Dorian Gray portrait warning about behavior modification? Was he saving my life?

Like Patti, I pulled back gently from the overload of the thrilling 1970s that were the heyday and last hurrah of my youth. At that time, forty-two years ago — the exact length of Robert’s short life, I was turning forty. Non, je ne regrette rien. He and I continued on ribald in person and raunchy in phone sex, modulating gradually into counseling and consoling each other in our late-night conversations and in the letters he wrote when he was lonely.

16

I saved the phone bills and his letters that ached with the isolation of the gifted artist for whom life was never intense enough. In his left-handed slant, he wrote on April 20, 1978 (which he misdated as 1977): “I think you’re right about me needing a psychiatrist. I’m a male nymphomaniac…. Just can’t get sex out of my head. I’m never satisfied. It will drive me mad. But otherwise, life doesn’t seem worth it. I’m probably going to have to find one person somehow that can keep me in. Otherwise my energy will just pick up and leave.”

On May 21, 1978, he wrote: “It’s midnight…I almost forgot to tell you. I let some creep stick his hand up my ass. I’ve been fisted — even came — but I think I prefer being the giver. I don’t seem to have any great desire for it to happen again. In fact, I can’t help but to give preferential treatment to the feeding process. I want to see the devil in us all. That’s my real turn on. The MDA is coming on stronger. I have to take a dump, but I’ll save it. I’m sure somebody out there is hungry. It’s time to get myself together, pack my skin in leather. The package is always important. Goodnight for now. I feel the pull to the West Side. The night is getting older. Love, Robert.”

September 12, 1979: “The ‘punk’ leather boy [Marcus Leatherdale] from San Francisco is getting more and more on my nerves. I hate naïve people. He just left wearing his motorcycle jacket. I feel as though he shouldn’t be allowed to wear it as he just doesn’t have a sophisticated sense of sex. I hate happy, naïve people. I guess I believe in total dictatorship with someone who thinks exactly like I do in charge. How’s that for ego? …I took pictures of Nick [Bienes] in color last week for a second possible Drummer cover…. I met that publisher from Drummer a couple of times in the bar. Nothing much else to report. Blood is in the air. Love, Robert.”

As he progressed into his Mandingo period of shooting black men, he confessed: “I’m still somewhat into [N-word plural]. I even have a button that spells it out that I wear to the bars. It seems to attract the dirty jiggers. Sex Sex Sex Sex — that’s all I think of. Let me out of this place. It’s driving me crazy.”

On April 10, 1978, on Hotel Boulderado letterhead, Robert, bored in Colorado, wrote: “Dear Jack — I just arrived here from New York. The London Times sent me to Boulder to take a picture of Allen Ginsberg. It sounds good, but I would prefer to be under the sheets in New York or even better in San Francisco. It makes me crazy when I travel, especially this sort of trip which is for less than 24 hours…. Thanks to you and your friends I’ve been spoiled. I haven’t really been satisfied since I left San Francisco. I miss you, Jack. I regret we never got into anything more while you were in New York the last time…It’s 10 P.M. I’m in bed already. I checked out the 3 bars near the hotel and nothing was happening on a Monday night in Boulder — at least I saw nothing. Besides, life has exhausted me.

“Ginsberg was a Jewish drag. He made me sit through his lecture on William Blake which was OK except that it reminded me of when I was in school as I had to make a great effort not to close my eyes and fall asleep. Then he complained about the Times spending the money to send a photographer out here as he’s had so many pictures taken already.”

Ginsberg, whom I had shot on Super-8 film on May 9, 1970, at the protest march on Washington after the shootings at Kent State, did not seem to catch on that this was not just another motor-driven camera hack; this was to be a portrait by Robert Mapplethorpe.

“Then he complained about having no time to make an effort. He finally decided to sit in the Lotus position barefoot. I quickly set up my lights which I had to drag out here and took 2 rolls (24) of film. I had wanted to do more than that as I came all the way and I do get nervous about the results. Somehow I brought up the subject of S&M and he did say (still in the Lotus position) that he was getting into it. No blood, however. Anyhow, by the time I was through, he was apologizing and invited me to meet him later at some Rock ‘n’ Roll club. I said I would, but I won’t. His day is up. The time for chanting is over. As far as I’m concerned, it never existed.

“I’m going to turn out the lights and try to muster up enough energy to ‘Jack’ off,” he fantasized. “ I’m going to think about having my fist up you while you…. Love, Robert.”

17

Let the art critics recount the international art world’s loss at the death of Robert Mapplethorpe so beloved by his own dear family. Let them explicate the wonders of his fourteen different printing processes, of his still-life studies of floral genitalia, of marble sculptures, of male and female nudes and fetishes and celebrity portraits, of all his shocking American gun photos, and of his cool sexualism. Let them wax jealous over his rich patron who knew art when he saw it and who saw the genius in Robert’s art.

Let them muse over his distinctive esthetic edge in sinister and beautifully violent, perhaps subtextually racial, pictures of a watermelon stabbed with a butcher knife: a black man’s hard shaft paired close-up and parallel with the barrel of a handgun held in his fist (Cock and Gun, 1982): and Robert himself, wearing a high-society white bow tie and a film-noir leather jacket, standing aspirationally as a Satanic terrorist in front of a pentagram holding in his gloved hands an automatic rifle.

In this 1983 Self-Portrait, Robert was quoting the iconic 1975 SLA “Tania” poster of the kidnapped San Francisco socialite and heiress Patty Hearst — who shot to fame in pop culture renamed “Tania” by Cinque, the handsome black leader of the Symbionese Liberation Army that had abducted and brainwashed her. In the “Tania” poster on the April 29, 1974, cover of Newsweek, Hearst was pictured solo wearing a revolutionary beret, brandishing an automatic rifle, and standing in Stockholm Syndrome solidarity with her kidnappers in front of the SLA’s terrorist symbol of the Seven Headed Cobra. Patty Hearst was a muse to Robert five years before she became a muse to filmmaker John Waters.

Let Paloma Picasso, and Willem de Kooning, the Louise’s Nevelson and Bourgeois, and Philip Glass, and the punk princess Gloria von Thurn und Taxis, and the royal San Francisco socialite Katherine Cebrian whom he photographed as a quote of “Whistler’s Mother” and adored because she was so rich and privileged she pronounced: “I don’t even butter my bread; I consider that cooking” — let them all be grateful Robert Mapplethorpe ever existed at all.

So many dead from AIDS, let us sit on the ground and tell sad tales of the death of kings and queens. Let me say I wonder and waver about the moody chiaroscuro portrait Robert shot of me. It’s a leap for a person to look at their portrait as art. Let me distance myself from whatever truth he sucked from my face that is so different from the truth I think of my face. Perhaps he broke the mask I had polished for forty years. Perhaps Robert, the salvific artist, forced me to look into my soul and change my ways. I wonder, did Richard Gere and Grace Jones and Yoko Ono feel somehow changed? Robert’s tongue never licked their eyeball. Robert’s lean body never made love to them. But his camera did. With his camera, he maybe saved my life. With my writing, I couldn’t save his.

I confess now that in my May 10, 1978, letter I lied to him: “Caro Roberto, …the portrait you took of me arrived. You’re good…. I see the way you slanted me. I should be so kind to you in the slant of my written vision of you. Two pieces are completed in which you figure: the article, short, in Drummer, and another piece, a barely fictionalized short story, in Corporal in Charge…. Take care, my good friend, I love you with all my head.”

Let the art world assess the artist and his art. Leave the private man — what does not belong to other friends and lovers — to me. We were too hot not to cool down, but how bright we shined in the Titanic 1970s before the iceberg of AIDS. As writer and photographer, as men, as fuckbuddies, as friends, something special passed between us. Revelation. Lust. Joy. Darkness and light. Good and evil. Understanding. Maybe even love.

18

We were what he said: intelligent people making excellent sex. That’s the value of ships passing in the night: reassurance that in the dark sea-swells, with Robert gone, his art living on, other talented lights, rising and falling, will certainly loom closer out of the distance, learn from his brilliance, and, in their own brief passage, prove once again that none of us, as I learned from him — playing Nick Carraway to his Jay Gatsby — borne back against the current, is forever alone.

Centuries from now, people will look at Mapplethorpe’s photographs, but what will they know of Robert, the kind sweet man who has no more memory than the remembrance we give him? As a monument to him, the Mapplethorpe archive at the Getty Museum Research Institute valued at millions contains his eye, head, heart, and gender in 120,000 negatives, 500 Polaroids, and 200 artworks of drawing, collage, sculpture, and jewelry. Robert through his Mapplethorpe Foundation bequeathed millions to AIDS research including grants to the two hospitals that treated him for AIDS: one million to Beth Israel Medical Center in New York and $300,000 to New England Deaconess Hospital in Boston where he died.

As he lay, oh, so very ill seven months before he died, he showed a visiting journalist a typed manuscript he kept close to his bed. Holding it out, he said, “This story is about me.” It was my 1978 short story, “Caro Ricardo,” which should have been titled “Caro Roberto.” But in the political turmoil of 1978, only six months before Harvey Milk was shot by an ex-cop, and with Christian soldiers marching onward with Anita Bryant and the Moral Majority, I felt that because of the story’s intimate eyewitness “take” on Robert, I needed to change his name to protect his private person who was not then at all as famous as he became in the 1980s when he courted any and all publicity — including the dramatically perfect moment of his brave performance art of “dying in public” at the Whitney exhibit to show the world, as had Rock Hudson in 1985, a personal face of AIDS.

From first to last with Robert, the danger from fundamentalist flamethrowers never stopped as the culture war revved up to burn women and gays at the stake. One hundred days after Robert died in 1989, tobacco-funded Republican Senator Jesse Helms, pitchfork in hand, dared denounce him on the floor of the U.S. Senate. In 1990, the outlandish city of Cincinnati dared to put seven of his photographs on trial for obscenity. I felt I had the right, the duty, the mandate even, assigned by him in 1977, to write that à clef metafiction “Caro Ricardo” while protecting him, because he had told me in pillow talk one rainy night on Bond Street, “I want to be a story told in beds at night around the world.” That private line, that caused us to giggle, became the iconic tag line under his self-portrait on the poster for Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato’s 2016 HBO documentary, Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures.

Robert Mapplethorpe was a creature of the night. Take a walk down Christopher Street after midnight. Peer in the windows of shops where we browsed for antiques. Robert was an offhand collector. He wrote impulsive, enormous checks for small bronze sculptures of the goat-footed devil. I think he will haunt those Village streets until his next incarnation. I think I am happy to be left with the memory of him and with the evil-smirking cover of Drummer, Biker for Hire, which is perhaps the most authentic color portrait work he ever shot. He so liked my friend, Elliott Siegal, the biker model I introduced him to, that he immediately shot him and his partner Dominick in multiple frames of religious martyrdom for his X Portfolio.

19

Robert came, saw, and conquered, but did he get what he wanted?

In the 1980s, Robert went to Heaven.

British film director Derek Jarman, who was his UK competition, remembered that one night at a party at Heaven — the psychedelic London disco under Charing Cross railway station — he was going down one crowded stairway as Robert was climbing up another, and Robert shouted out, “I have everything I want, Derek. Have you got everything you want?”

In his radically American book Representative Men, Ralph Waldo Emerson following Plutarch and Thomas Carlyle wrote about society’s need for Great Men whose talents have a decisive historical effect. Robert had the primacy of personality and the heroic genius necessary to change culture. The altar boy from Floral Park dared rise up to reveal how vulnerable and strong and valuable we homosexuals can be as seers and sayers explaining truths of the human condition to a blind and deaf society. In all my writing about him in books, magazines, and newspapers, I carry him in my heart where the memory of his mind, heart, sex, and seed sustains me. Is this the reminiscence you wanted from me, Roberto? Caro Roberto!