NON-FICTION BOOK

by Jack Fritscher

How to Quote from this Material

Copyright Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. & Mark Hemry - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

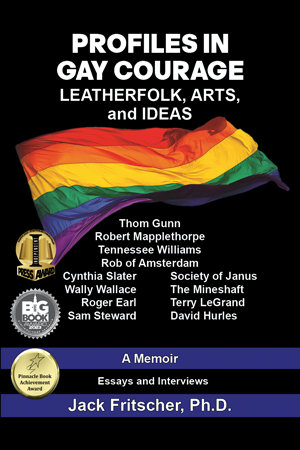

PROFILES IN GAY COURAGE

Leatherfolk, Arts, and Ideas

Volume 1

by Jack Fritscher, PhD

TENNESSEE WILLIAMS

1911-1983

“We All Live on Half of Something”

Playbill Essay for the New York Art Theater Production of

Something Cloudy, Something Clear

A Play by Tennessee Williams, Directed by Anatole

Fourmantchouk, Theater at St. Clement’s

Author’s Note. My essay, “We All Live on Half of Something,” here redux, was published in Playbill: On Stage, September 2001, for the New York Art Theater Production of Something Cloudy, Something Clear. A Play by Tennessee Williams. Directed by Anatole Fourmantchouk. Theater at St. Clement’s, 423 West 46th Street.

Director Fourmantchouk, defining his unique production, gave me the typed pages of his script and explained: “The New York Art Theater is working from a copy of an original uncensored and unpublished version of the play.”

This Playbill issue was distributed to audiences during early September previews until the run was abruptly stopped by the World Trade Center attack on 9/11. In the troubled urban aftermath, the play returned for opening night on September 20 and closed on October 1.

* * * *

There exists a famous 1941 photograph of a fit Tennessee Williams, 30, striding the beach, stripped to the waist, and wearing a sailor’s white bell-bottoms. Such portrait of the artist as a young man makes Tennessee poster-boy for his autobiographical play, Something Cloudy, Something Clear. Set on the shifting sands of time in the Provincetown dunes, this 1941 postmodern memory play is more personal than a writer’s riff on Luigi Pirandello’s 1921 modernist Six Characters in Search of an Author. Pirandello’s characters struggle like the characters in Cloudy/Clear and complain that they are the incomplete faces of an author who can’t finalize the play for which they were invented.

In the several drafts of Cloudy/Clear, the very “august” Williams, an author in search of himself, duplicates and names himself as “August” after the equinox month of shooting stars during which this romantic summer-place drama occurs — and in homage to August Strindberg whose streaming A Dream Play he admired. The twin character framed as Tennessee/August is so personal in this “august portrait” that it may as well be played naked — as August is, at the end of act one, when he says, “Present and past, yes, a sort of double exposure.”

This is an opportunity to get into the moving parts of a master playwright’s head. Tennessee Williams has always been his own best script doctor. In 1941, he wrote his first draft, Purification, set on the Provincetown wharf where he met his golden lover for the summer, Kip Kiernan. Inspired and bedeviled by Kip’s unrequited love, he soon rewrote and re-titled his second draft of their affair, Parade, Or, Approaching the End of Summer.

In 1962, he titled his third version of Purification/Parade as Something Cloudy, Something Clear. In 1981, the first production of that unpublished script was directed by Eve Adamson for the Jean Cocteau Repertory Company and supervised by Williams himself Off-Off Broadway at the Bouwerie Lane Theater. It was the last Williams play produced in New York City during his lifetime. In 1983, he died by accidental suffocation, age 71, choking on an inhaled plastic cap from a nasal medication bottle in the Sunset Suite at the Hotel Elysée in Manhattan.

The play’s present force, coming from the past, thrusts formatively into the future. Five hundred years from now, actors — genetically wired to his texts in the manner of Marlon Brando, Vivien Leigh, Elizabeth Ashley, Vanessa Redgrave, and Anna Magnani for whom he wrote The Rose Tattoo — will be performing his plays, because Williams writes his words to and for the actors. Good actors play a script the way musicians play a score: live and perhaps differently each time. Once more, with feeling. In Cloudy/Clear, Williams, folding time, announces his double-exposure frame of remembrance of things past: “Life is all — it’s just one time. It finally seems to occur at one time.”

Poetically, the geography of Tennessee Williams’ body is the horizon of this unabashedly gay-themed play. The author’s eyes, hidden in real life by dark glasses, are title and central symbol: his left eye, cloudy before age 30 with a cataract (of lust, he said); his right eye clear (with love, he also said).

He wrote of Kip Kiernan in a 1940 letter to Donald Windham, “I lean over him in the night and memorize the geography of his body with my hands.” Sex becomes the poetry of memory. Williams, always aggressive sexually, idolizes the Platonic Ideal of the perfect lover even as perfect young bodies romantically decay. Kip has brain cancer; Clare, an anagram of clear, clear as a conscience, has half a kidney; August has one white eye.

Kip needs brain surgery to recover his health. Violet in Suddenly Last Summer demands unnecessary brain surgery to silence Catherine’s truth about cannibalism: “Cut this hideous story out of her brain.” Williams, haunted by his sister Rose’s surgical impairment by lobotomy, gave one of his short-story collections about broken bodies and souls, struggling with one arm tied behind their backs, a title of disability: One Arm. This anthology title of existential amputation and loss is repeated in his prison death-row short story, “One Arm,” and in his screenplay, One Arm. In addition to his plays, he wrote eight original screenplays: The Glass Menagerie, A Streetcar Named Desire, The Rose Tattoo, The Loss of a Teardrop Diamond, The Fugitive Kind, Boom! (The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore), and One Arm.

Gorgeously doomed, Williams’ creatures live as erotic castaways. They seek SOS rescue on the proscenium beach which the author warns in Suddenly Last Summer, Night of the Iguana, Milk Train, and Small Craft Warnings is a dangerous place for poets and priests and women. If aliens knew of Earth only from the plays of Tennessee Williams, they’d judge the planet to be a tropical rain forest, a ruined Garden of Eden, filled with overheated men and under-ventilated women. So integral is Williams in popular culture, his dramas like Un Tramway Nommé Désir, Un Deseo de Nombre de Tranvía, and ‘N Tram Genaamd Begeerte, continue to play globally in dozens of translations. The 1951 film of A Streetcar Named Desire is number 45 on the American Film Institute’s list of Top 100 Films. The San Francisco Opera commissioned an operatic version of Streetcar that premiered in 1998.

These lost souls find God in the convergences of sex and in the violence of the natural universe. In A Streetcar Named Desire, Blanche is the desperate descendent of the desperate Scarlett O’Hara by way of origin, sensibility, and casting. Frantically seeking rescue by a gentleman caller, she declares a magical main theme in Williams’ dramas, “Suddenly there is God so quickly.” Maybe. But what if he is the vengeful God of the Encantadas? In Suddenly Last Summer when Sebastian freaks out in a sex-panic, he screams, “Complain? To the Manager? What manager? God?”

Will God rescue us or not? Williams is ambivalent about theological rescue, about salvation itself, which Big Daddy in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof rails against so hysterically. Sometimes God is found suddenly in love, sometimes in violence, sometimes in sex, sometimes in absentia. The long-missing father in Menagerie “was a telephone man who fell in love with long distances.” God is something cloudy, something clear. The only theological certainty Williams wrote in his Memoir is “God don’t come when you want Him but He’s right on time.”

In Cloudy/Clear Williams turns his affaire de coeur into a queer cri de coeur. Because Tennessee grew up as a nelly boy beaten up by a sexy bully boy named Brick Gotcher, he rejected the masochism of effeminacy and built his esthetic of masculinity romancing ideas about straight men. His play hangs its heart on a quintessential gay fantasy: the impossible petard of loving and being loved by a straight man.

In Lord Byron’s 1824 poem, “Love and Death,” the windswept poet — beloved by Williams who resurrected him in his 1946 Lord Byron’s Love Letter and his 1953 Camino Real — loves a young straight soldier who does not love him back. In August’s unrequited love for Kip, Williams dramatizes homosexuality’s Catch 22.

If a straight man reciprocates, what is the meaning of straight? Brick, the temporarily disabled football hero, querying homomasculine intimacy with his buddy Skipper, tackles similar tensions about the nature of male love in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Where does Tennessee begin to transgress, or not transgress, queer politics?

With his alpha-male protagonists, he distanced himself from drag, swish, and camp which he called degrading forms of self-mockery. Is Blanche the closest he ever came to coding a drag queen? During the 1956 Broadway revival of Streetcar, he told his star and dear friend Tallulah Bankhead, whom he had in mind while creating the role, that she was the worst Blanche he had ever seen because she, as a gay icon, camped up the sensitive part to play to her cheering gay fans.

In Stella’s “Stanley,” Williams and Brando launched a new postwar torn-T-shirt standard of masculine beauty. Their rough-trade blue-collar male sex appeal sold tickets and liberated pop culture’s gaze at men in the conformist 1950s via Marlon’s sweaty factory worker in Streetcar and his Hells Angels biker in The Wild One which unreels as if it were Stanley’s backstory. Even today, years later, personals ads in the gay press cry out from the heart for authentic “straight acting, straight-appearing.” But what is that? Blanche queries Stanley: “Straight? What is straight? A line can be straight, or a street, but the human heart, oh, no, it’s curved like a road through mountains.”

That oh-so-declarative sentence of sexual politics is so at Williams’ short hairs, he re-quotes it exactly in his Memoirs. Even so, as with an original all-male Shakespeare production in 1605, Williams greatly approved of an all-gay, all-male, but non-camp, non-drag staging of Gertrude Stein’s Four Saints in Three Acts.

Does anyone in the audience care about the politics, theology, or esthetic of Tom/Tennessee, the person, the isolato, all alone in his room? Or is it all about Stanley and Blanche and Maggie and Violet Venable and the Princess Kosmonopolis, characters chewing scenery for a packed house? “His plays have their own reputations,” wrote Williams’ biographer, Lyle Leverich. Is it worthwhile knowing how the author was dumped? By Kip Kiernan for a woman. By the critics grown brittle to his poetic passions.

Hot for twenty years on Broadway and in Hollywood, Williams was cast away in the 1960s when critics moved on to the next Fifteen Minutes of someone else. His plays and movies became box-office disappointments like the 1966 film This Property Is Condemned and the 1968 Boom! Nevertheless, he kept writing and revising. As a positive result, his canon remains in constant motion on, off, and far from Broadway. Annually, his plays — whose titles alone sell tickets — top the lists of any year’s most revived dramas. The Glass Menagerie is the straight play most revived on Broadway during the last seventy years.

In the early 1940s, MGM hired Williams to write a screenplay for Lana Turner. When he wrote Girl in Glass, MGM hated it and fired him. When re-worked, The Glass Menagerie became a Broadway hit. MGM had to bid for film rights to a property it once owned, and lost to Warner Bros.

In Cloudy/Clear, Williams articulates his anger at market-driven artists’ concessions to bad taste to sell tickets. He writes of the “exigencies of desperation” and the “negotiation of terms.” The theater, he said, is “little sentiment and all machinations.” In his Memoir, he writes of suffering depression and scoring “uppers” from “Dr. Feel Good” in “the disastrous decade of my sixties.” Witnessing his stress in commercial theater, his own mother said, “Tom, it’s time for you to find another occupation now.” He described her as “a little Prussian officer in drag.”

Despite his addictions, he tried to keep his unclouded voice clear. Personality cannot be replaced. He declared in his Memoir: “The individual is ruthlessly discarded for the old, old consideration of profit.” What other American dramatist, age 65ish in the mid-1970s, was rebel enough to read his own poetry free to all — no charge — at the 92nd Street Y? What to producers was money, and today is politics, were to him heartfelt themes in the universal human condition.

The ravenous Sebastian Venable in Suddenly was eaten alive trying to write his poem of summer. “Fed up with dark ones, famished for blonds…[Sebastian] talked about people as if they were items on a menu. That one’s delicious-looking.” Cannibalism may be Williams’ metaphor for what he calls “the cruel exigencies of theater.” Cannibalism is what critics, producers, and agents do to artists, what straight society does to queers, and what gay culture does to its own.

The dramatic-poet Williams never impedes narrative or character by explaining the metaphor of “cannibalism.” The audience is left properly to its own magical and critical thinking. Perfect. Entertainment gives you what you expect and does not disturb you. Art snaps you around with disruptions you don’t expect — and you exit the theater changed.

Williams, writing so very precisely about the human condition, forges a daring list of charged topics: homosexual identity (Cloudy/Clear, Cat, Suddenly Last Summer), disability (The Glass Menagerie, “One Arm”), race (“Desire and the Black Masseur,” “Why Did Desdemona Love the Moor?”), homelessness and definitions of family (Streetcar, Cat, Camino Real), domestic abuse and victimization (Streetcar, Cat, Suddenly), fertility (Streetcar, Cat), drugs and aging (Cat, Sweet Bird of Youth, The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone), sex tourism (Suddenly, Roman Spring, Iguana), health care (Streetcar, Cat, Summer and Smoke, Suddenly), immigration (Cloudy/Clear, Orpheus Descending), and women’s rights (throughout his canon). Without explaining himself or his plays, he leaves the messages to Western Union. Tennessee Williams, influenced by writers Hart Crane, D. H. Lawrence, and Rainer Maria Rilke, is the most poetic of American dramatists and the most dramatic of American poets.

The emerging joy of Tennessee Williams’ “unpublished” plays — precisely like this singular version for this New York Art Theater — is the sense of discovery of the person, of the author himself, as times change into new rich readings of his autobiographical work. After we know the big plays of the last midcentury, we want to know the artist, because the artist, in our time, matters as much as the art. Vanessa Redgrave, more than once famously outcast for her humanist mixing of art with politics, in 1997 dug up and starred in Williams’1938 play about fascism, Not About Nightingales. Variety reviewed it in 1998 as “angry, propagandistic Williams, a young firebrand with an idealist’s fervor.”

Williams adored Redgrave. He proclaimed, “Vanessa Redgrave is the greatest actress of our time.” The Redgrave dynasty has long championed Williams alongside his beloved Chekov. Vanessa triumphed as Lady Torrance in Orpheus Descending, the final version of Battle of Angels which Williams was writing while living the action of what became Cloudy/Clear. Her brother Corin Redgrave starred in Not About Nightingales, directed by Trevor Nunn. Her sister Lynn Redgrave played Arkadina in The Notebook of Trigorin. Her daughter Natasha Richardson played Blanche in Streetcar and Catherine Holly in Suddenly Last Summer.

Amazingly, Trigorin is an almost perfect fusion of two great international playwrights: Chekov and Williams. In the free-wheeling last year of his life, Tennessee re-wrote The Seagull as Trigorin. He made the text his own in more ways than turning Chekov’s plot bisexual — something he could not do to Kip Kiernan. In 1963, during Vanessa’s marriage to Tony Richardson, the bisexual Richardson was directing The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore starring Williams’ longtime bisexual friend Tallulah Bankhead. About her who appears fictively in a brief dream in Cloudy/Clear, he wrote she is “The strongest of all the hurt people I’ve ever known.”

The Williams-Redgrave solidarity was a long, strong bond. In 1980, Tennessee flew to Boston to support Vanessa in her lawsuit against the Boston Symphony which had canceled her appearance because of pressure opposing her political views. Banned from the Boston Symphony stage, Vanessa booked herself into Boston’s Orpheum Theatre where in a protest performance she offered songs and dances from As You Like It, The Seagull, and Isadora.

Tennessee twice joined in and ascended the Orpheum stage with Vanessa, his star of Orpheus Descending, to read his essay, “The Misunderstanding and Fears of an Artist’s Revolt.” That year, before his death in 1983, isolated and suffering the cruelty of the commercial art world, Tennessee, Redgrave wrote, was so out of fashion the newspapers did not bother to report his appearance.

The action in Cloudy/Clear happens three years before The Glass Menagerie, his second memory play, made Williams famous in 1944. The characters, except for Clare, are real people. Kip was Williams’ straight lover, a Canadian dancer who resembled Nijinsky, who had changed his Russian-Jewish name, Bernard Dubowsky, to Kip Kiernan. Kip feared Tennessee was so good a gay lover that he was turning him homosexual. In 1947, after the estranged Kip died in 1944, Frank Merlo became his lover for the next fourteen years.

In the cast of Cloudy/Clear, filmstar Miriam Hopkins, who in 1940 starred as Myra Torrance in his ill-fated flop, Battle of Angels, became his fictitious “Caroline Wales.” Producers Lawrence Langner, his wife Armina Marshall, and the Theatre Guild’s Theresa Helburn were merged into the self-serving cannibal agents “Maurice and Celeste Fiddler” to whose tune August does not dance.

So many of Williams’ characters on the beach — which is the proscenium stage of planet Earth — endure the gravitational pull of the moon and sea on the geography of the body. Stranded like Sebastian’s Encantada turtles on the sands of beaches calling for help, even on the shore of Moon Lake, they, like the Reverend Shannon in Iguana want to take the long swim from the beach to China knowing that Christopher Flanders, the angel of death in Milk Train, is no catcher in the rye come to save them. He is their escort, their final walker — there to help them die. He is a “lifeguard in reverse” who helps suicidal desperadoes stuck on the shore step into the long swim in the drowning sea.

Penning poetry in his free-style dialogue, Williams observes Aristotle’s strict unities of time, place, and action while thrusting forward with a dramatic dialectic. Structurally, in play after play, thesis meets antithesis and creates synthesis. Everyone in Williams’ world of determinism is on a collision course. Stanley says to Blanche, “We’ve had this date from the very beginning.” In Cloudy/Clear, gay identity arm-wrestles with straight identity. The play itself repeatedly intones that there are Clare’s and Kip’s “exigencies of desperation” and “negotiation of terms.” Williams, the humanist, keeps the humanity of diverse sexual identities alive.

He is not at all like his New Orleans friend, the flamboyant poet, Oliver Evans, whom he first met in Provincetown on the wharf in the summer of 1941 while writing Cloudy/Clear. He and Evans became lifelong friends, traveled together, and enjoyed, à trois, many a ménagerie, Evans told him over drinks in a New Orleans bar on September 14, 1941: “A healthy society does not need [homosexual] artists….We are the rotten apple in the barrel…in fact all artists ought to be exterminated by the age of 25.” Williams, never a self-hating homosexual, responded to Evans’ problematic take on homosexuality, “I am a deeper and warmer and kinder man for my deviations.”

With incredible tenderness, Williams closes Something Cloudy, Something Clear when August intones: “Child of God…” August is now almost become Saint Augustine. The Episcopalian Williams, who based the structure of Streetcar on the dramatic structure of the Anglican/Catholic Mass, became a Roman Catholic in 1969 because he liked the theatrical pageantry and incense.

August addresses Kip and Clare in the last lines of this version of this script for this production about which director Fourmantchouk, distancing himself from the 1981 version that did not contain this exchange, wrote: “The New York Art Theater is working from a copy of an original uncensored and unpublished version of the play.”

Touching Kip’s face and throat, August says to Kip: “Child of God — you — don’t exist anymore.” Clare chimes in, “Neither do you.” August, the poet, finally clear about his cloudy existence, asserts in one defining sentence the sustaining magic and power of memory, of storytelling, of theater, of writers voicing theater, of actors performing theater, of audiences watching theater. He retorts with his Proustian reason for being: “At this moment, I do, in order to remember.”