WRITING ON

TENNESSEE WILLIAMS

How to Quote from this Material

Copyright Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. & Mark Hemry - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

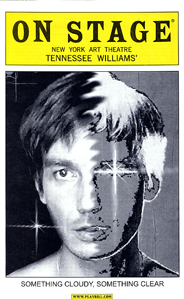

Published in Playbill, On Stage, September 20, 2001

Essay for the New York Art Theater Production of Something Cloudy, Something Clear,

A Play by Tennessee Williams, Directed by Anatole Fourmantchouk,

Theater at St. Clement’s, 423 West 46 th Street (off 9 th Ave.)

Autumn 2001

©2001 Jack Fritscher

Feature Article also available in PDF

We All Live on Half of Something

by

Jack Fritscher

There exists a famous 1943 photograph of a buffed Tennessee Williams, 32, striding the beach, stripped to the waist, and wearing a sailor’s white bell-bottoms. Such portrait of the artist as a young man makes Tennessee poster-boy for his 1941 autobiographical play, Something Cloudy, Something Clear. Set on the shifting sands of time in the Provincetown dunes, this memory play is more personal than a riff on Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author. In Cloudy/Clear, the august Williams names himself “August” after the equinox month of shooting stars during which this summer play occurs, and in homage to August Strindberg whose A Dream Play he admired. The character of Tennessee/August may as well be played naked, as he is at the end of act one, so personal is the “august portrait.” August says, “Present and past, yes, a sort of double exposure.”

This is an opportunity to get into a master playwright’s head. Tennessee Williams has always been his own best revisionist. In 1941 he wrote Purification which took place on the Provincetown wharf where he met his actual lover for the summer, Kip Kiernan. Early on, he rewrote and re-titled an analog revision, Parade, Or, Approaching the End of Summer. In 1962 he titled a new scripting of Purification/Parade, Something Cloudy, Something Clear. The first production of this unpublished script was supervised by Tennessee Off-Off Broadway in 1981. (Williams: 1911-1983, Hotel Elysse, Manahattan) The play’s present force, coming from the past, thrusts formatively into the future. Five hundred years from now, actors–genetically wired to his texts in the manner of Elizabeth Ashley–will be performing his plays, because Williams offers his words to actors. Good actors play a script the way musicians play a score: live and perhaps differently each time. In Cloudy/Clear, Williams announces his double-exposure theorem of remembrance of things past: “Life is all–it’s just one time. It finally seems to occur at one time.”

Poetically, the geography of Tennessee Williams’ body is the horizon of this unabashedly gaythemed play. The author’s eyes, hidden in real life by dark glasses, are title and central symbol: his left eye, cloudy before age 30 with premature cataract (of lust, he says); his right eye clear (with love, he also says). He wrote of Kip Kiernan in a 1940 letter to Donald Windham, “I lean over him in the night and memorize the geography of his body with my hands.” Sex becomes the poetry of memory. Williams, always aggressive sexually, idolizes the Platonic Ideal of the perfect lover even as bodies romantically decay. Kip has brain cancer; Clare, clear as a conscience, has half a kidney; August has one “white eye.” (Williams’ gave one of his several short story collections the amputated title, One Arm, the same title as one of his six original screenplays.)

Gorgeously doomed, Williams’ creatures live as erotic castaways. They seek rescue on the proscenium beach which the author warns in Suddenly Last Summer, Night of the Iguana, and Small Craft Warnings is a dangerous place for poets and priests and women. If aliens knew of Earth only from the plays of Tennessee Williams, they’d judge the planet to be a tropical rain forest filled with overheated men and under-ventilated women. So integral is Williams in popular culture, the film version of A Streetcar Named Desire is number 45 on the American Film Institute’s list of Top 100 Films; and the San Francisco Opera commissioned an operatic version that premiered in 1998. These lost souls find God in the details of sex. In A Streetcar Named Desire, Blanche, desperately seeking rescue by a gentleman caller, declares a magical main theme in Williams’ dramas, “Suddenly there is God so quickly.” Maybe. In Suddenly Last Summer when Sebastian freaks out in a sex-panic, he screams, “Complain? To the Manager? What manager? God?” Williams is ambivalent about theological rescue, about salvation itself which Big Daddy in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof so wants. Sometimes God is found suddenly in love, sometimes in violence, sometimes in sex, sometimes in absentia. God is something cloudy, something clear. The only theological certainty Williams wrote in his Memoir is, “God don’t come when you want Him but He’s right on time.”

In Cloudy/Clear Williams turns his affaire de coeur into a queer cri de coeur. Because Tennessee never liked effeminacy, the play spikes on another quintessential gay fantasy: the impossible desire to love and be loved by a straight man. In his unrequited love for Kip, he dramatizes homosexuality’s catch 22. If a straight man reciprocates, what is the meaning of straight ? Brick, the football hero, resisting gay life ala Kip, parses similar homomasculine tension about the nature of male love in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Where does Tennessee begin to transgress, or not transgress, queer politics? He distanced himself from drag, swish, and camp as degrading forms of self-mockery. Actually, personals ads in today’s politically correct gay-press cry out for “straight acting, straight-appearing.” Blanche queries Stanley: “Straight? What is straight? A line can be straight, or a street, but the human heart, oh, no, it’s curved like a road through mountains.” That oh-so-declarative sentence of sexual politics is so at his short hairs, Tennessee re-quotes it exactly in his own very readable Memoirs (1972). Even so, as with an all-male Shakespeare production, Williams greatly approved of an all-gay, all-male, but non-camp, non-drag staging of Gertrude Stein’s Four Saints in Three Acts.

Does anyone in the audience care about the politics, theology, or esthetic of Williams, the person all alone in his room? Or is it all about Stanley and Blanche and Maggie and the Princess Kosmonopolis, characters chewing scenery for a packed house? His plays have their own reputations writes Williams biographer, Lyle Leverich. Is it worthwhile knowing how the author was dumped? Hot for fifteen years on Broadway and in Hollywood, Williams was castaway in the 1960s when critics moved on to the next 15 minutes. His plays and movies were gone with the box office, but he kept writing and revising. (In the early 1940’s, MGM hired Williams to write a screenplay for Lana Turner. When he wrote Girl in Glass, MGM fired him. Ironically, when The Glass Menagerie became a hit, MGM had to bid for film rights to property it once owned. In Cloudy/Clear, he articulates his anger at market-driven artists’ concessions to bad taste to sell tickets. He writes of the “exigencies of desperation” and the “negotiation of terms.” The theater, he said, is “little sentiment and all machinations.” In his Memoir, he writes of depression and Dr. Feel Good in “the disastrous decade of my sixties.” Even his mother, true to Amanda and untrue to Mrs. Venable, said, “Tom, it’s time for you to find another occupation now.” He described his own mother as “a little Prussian officer in drag.” He tried to keep his unclouded voice clear. Personality cannot be replaced. He declares in his Memoir: “The individual is ruthlessly discarded for the old, old consideration of profit.” What other American dramatist, age 65ish in the mid-70’s, was fuck-you enough to read his own poetry at the 92nd Street Y? What to producers was money, and today is politics to us, were to him dramatic themes in the human condition. Sebastian Venable in Suddenly was eaten alive trying to write his poem of summer. Cannibalism may be his metaphor for what he calls in his Memoirs “the cruel exigencies of theater.” Cannibalism is what critics, producers, and agents do to artists, for what straight society does to queers, or for what gay culture does to its own. Neither fundamentalist nor literalist, the humanist poet Williams never impedes narrative or character by explaining “cannibalism.” The audience is left on its own. Perfect. Entertainment gives you what you expect and does not disturb you. Art snaps you around with what you didn’t expect and you leave the theater changed.

Williams’ writing so very precisely about the human condition tackles a list of what have become politically charged topics: sexual preference ( Cloudy/Closer, Cat, Suddenly Last Summer ), disability ( The Glass Menagerie ), race (“Desire and the Black Masseur”), homelessness and definitions of family ( Streetcar ), fertility ( Streetcar, Cat ), drugs and aging ( Cat, Sweet Bird of Youth ), health care ( Cat, Suddenly, Summer and Smoke ), immigration ( Cloudy/Clear, Orpheus Descending ), and women’s rights (throughout his canon). Without explaining himself or his plays, he leaves the messages to Western Union. Tennessee Williams, influenced by writers Hart Crane, D. H. Lawrence, and Rainer Maria Rilke, is the most poetic of American dramatists and the most dramatic of American poets.

The emerging joy of Tennessee Williams’ “unpublished” plays is the sense of discovery of the person himself. After we know the big plays of the last mid-century, we want to know the artist, because the artist, in fact, matters as much as the art. Vanessa Redgrave, more than once famously outcast for her humanist mixing art with politics, in 1997 unearthed Williams’1938 play about fascism, Not About Nightingales. Variety reviewed it in 1998 as “angry, propagandistic Williams, a young firebrand with an idealist’s fervor.” Williams adored Redgrave. He proclaimed, “Vanessa Redgrave is the greatest actress of our time.” The Redgrave dynasty has long championed Williams alongside Chekov. Vanessa triumphed as Lady Torrance in Orpheus Descending, the final version of Battle of Angels which Williams was writing during the action of Cloudy/Clear. Corin Redgrave starred in Not About Nightingales, directed by Trevor Nunn. Lynn Redgrave played Arkadina in The Notebook of Trigorin. Amazingly, Trigorin is an amazing fusion of two great playwrights: Chekov and Williams. In the free-wheeling last year of his life, Tennessee re-wrote The Seagull as Trigorin. He made the text his own in more ways than turning Chekov’s plot bi-sexual. During Vanessa’s marriage to Tony Richardson, in 1963 Richardson was directing Milk Train starring Tallulah Bankhead who “appears” briefly in Cloudy/Clear. The Williams- Redgrave solidarity was a long, strong bond. In 1980, Tennessee flew to Boston to support Vanessa Redgrave in her case against the Boston Symphony which had canceled her appearance, apparently because of political pressure about her political views. Alternative to the Boston Symphony stage, Vanessa was booked into Boston’s Orpheum Theatre where in a protest performance she offered songs and dances from As You Like It, The Seagull, and Isadora. Tennessee twice mounted the Orpheum stage with Vanessa, his star of Orpheus Descending, to read the essay, “Misunderstanding of the Artist in Revolt.” That year before his death, isolated and suffering the cruelty of the commercial art world, Tennessee, Redgrave wrote, was so out of fashion the newspapers did not bother to report his appearance.

The action in Cloudy/Clear happens seven years before The Glass Menagerie made Williams famous. The characters, except for Clare, are real people. Kip was Williams’ straight lover, a Canadian who resembled Nijinsky, who had changed his Russian-Jewish name, Bernard Dubowsky, to Kip Kiernan,. Kip feared Tennessee was such a good lover that he was turning him homosexual. Frank Merlo was Williams’ gay lover. Miriam Hopkins, who starred in the ill-fated Battle of Angels, was Caroline Wales. Producers Lawrence Langner, his wife Armina Marshall and the Theatre Guild’s Theresa Helburn amalgamated into Maurice and Celeste Fiddler. These people on the beach, which is the proscenium stage of planet Earth, endure the gravitational forces of the geography of the body. For all his seemingly spontaneous writing of poetry, Williams observes a dramatic dialectic. Structurally, in play after play, thesis meets antithesis and creates synthesis. Everyone in Williams’ world is on a collision course. Stanley says to Blanche, “We’ve had this date from the very beginning.” In Cloudy/Clear, gay identity collides with straight identity. The play itself repeatedly intones that there are Clare’s and Kip’s “exigencies of desperation” and “negotiation of terms.” Williams, the humanist, keeps the humanity of both sexual identities alive. He is not at all like the poet Oliver Evans, quoted in the play, who believes “a healthy society does not need artists.” Evans told Williams, “...in fact all artists ought to be exterminated by the age of 25.” Williams, never the man of guilt, responded to Evans in a letter, “I am a deeper and warmer and kinder man for my deviation.”

With incredible tenderness, Williams closes Something Cloudy, Something Clear. “Child of God...” August is now almost become St. Augustine. The Episcopalian Williams became a Roman Catholic in his final years. Tennessee had written in an introduction to Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, “My goal is just somehow to capture the constantly evanescent quality of existence.” August says in the last lines of Cloudy/Clear to Clare, “You–don’t exist anymore.” Clare responds, “Neither do you.” August, the poet, in final existential clarity, conjures the magic of storytelling, of theater itself, of actors performing theater, of audiences watching theater. “At this moment, I do, in order to remember.”

Writing completed 21 July 2001

©2001 Jack Fritscher