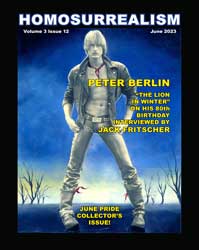

HOMOSURREASLISM Magazine

Feature Articles: Gay Press by

Jack Fritscher

Feature Article also available in PDF and Flipbook

Homosurrealism magazine June Pride Issue

Volume 3 Issue 12 June 2023

PETER BERLIN

AFTERNOON TEA WITH “THE LION IN WINTER”

Celebrating the 80th Birthday

of Homosurrealist Artist and Icon Peter Berlin,

the Avatar of Armin Hagen Freiherr von Hoyningen-Huene

in Conversation with Jack Fritscher

San Francisco November 11, 2022

A Treatment for a Screenplay

The Peter Berlin Story

Jack Fritscher: Hello, Armin Hagen Freiherr von Hoyningen-Huene. Is Peter Berlin available?

Peter Berlin: Peter Berlin is not.

Jack Fritscher: Mr. Berlin has left the country?

Peter Berlin: [Laughs] Yes. He left about twenty years ago.

Jack Fritscher: He left twenty years ago? Your avatar left?

Peter Berlin: What is left of my dream lover is me, Armin.

Jack Fritscher: Sorry. Could you please speak a little louder?

Peter Berlin: Oh. Oh. Now, yeah, you see I’m frail and old. Right?

Jack Fritscher: That makes a pair of us. You’re three years younger. That’s why I’m calling because your seniority perhaps frees you to say new things you’ve never said before. I wish we could meet in person as we have so often, but I’m now entering my fourth year of strict Covid quarantine. You’re probably reclined on that lovely bed in your apartment you’ve photographed so perfectly. There are many interviews of Peter Berlin. I would like to interview Armin Heune.

Peter Berlin: Yes. I’m only doing this interview because I realize you are such a good writer. I’m not saying it to flatter you, but I guess you would give your work high grades. Right?

Jack Fritscher: [Laughs] Well, in the way you appreciate your work, I understand mine.

Peter Berlin: Of course, of course. What I feel about my own work, which I don’t even call work, I was just shooting pictures of myself.

[Shooting on location in the 1970s, Peter lensed his modernist Self-Portrait in Painter’s Cover-Alls and his nude Self-Portrait on the Roof of the Ansonia Hotel while the Ansonia housed the orgiastic Continental Baths in its basement where Bette Midler sang with Barry Manilow on piano to gay audiences in white towels.]

Peter Berlin: It was for no other reason than just, you know, capturing my daily sort of life. I must confess that I never owned a motorcycle. You know Buena Vista Park the way it was when cars could drive to the top and there was motorcycle parking? Well, I just climbed on one of the parked bikes and took my picture and left.

Jack Fritscher: To thine own selfie be true. Your transition into Peter Berlin created a foundational gay character that captured the gay imagination just after Stonewall. In fact, you arrived in America in 1969. In the 1960s when you were creating “Peter Berlin” on your body, John Waters was creating “Divine” on the body of Glenn Milstead, and Andy Warhol was creating “Little Joe” on the body of Joe Dallesandro.

Peter Berlin: The Swinging Sixties. “Divine” had Waters. “Peter” had me. Everything is timing, yes? I wish I had the time and talent to write, to sing, to make music. I haven’t done any work for years. I’m not proud of it. The direction of the human race distresses me. Who cares about Peter Berlin? The planet is sending messages that something bad is happening, and no one cares about it. That’s on my mind. Why should Peter make another photograph?

Jack Fritscher: In a toxic world.

Peter Berlin: I nearly called you to cancel because sometimes I have these episodes of really feeling not good.

Jack Fritscher: I’m sorry to hear that and happy you didn’t cancel. You’re a trooper.

Peter Berlin: For years, doctors have looked at my heart and poked this and tested that, and other things, and never could really diagnose anything. Then it sort of subsided. So now, once in a while, I have these odd feelings of lightheadedness and nausea.

Jack Fritscher: We’ve lived through AIDS and Covid and the collapse of San Francisco and shades of Sondheim’s ladies who lunch: “We’re still here.” Even though neither of us has AIDS or coronavirus, we’re still “Black Leather Swans” with mileage from the last mid-century. And we’re moulting.

Peter Berlin: [Laughs] Now I’m feeling fine.

Jack Fritscher: You’re celebrating your 80th birthday coming up on December 28th, aren’t you?

Peter Berlin: Did you look it up? There’s a lot online with the many interviews I’ve given over the years for magazines.

Jack Fritscher: I did look up your date of birth. Actually, I first wrote about you forty-two years ago in Skin magazine.

[Skin magazine, Vol. 2 No 6, 1981, “Peter Berlin - The Gay Garbo, A Legend in His Own Time” and again a mention in Drummer, issue 123, 1988, “Solo Sex: Who’s Who in J/O Video. A Guide to Surviving a Hard Day’s Night in the Age of AIDS Abstinence.”]

Jack Fritscher: If you recall, we’ve been acquainted since the early 1970s on Polk Street, plus while I was editor of Drummer and Robert Mapplethorpe shot you on Fire Island [1977] and me in New York [1978].

Peter Berlin: That’s right.

[Drummer 123, September 1988: With AIDS deaths raging, I wrote the “Solo Sex” feature to introduce readers to the safe sex of masturbation while watching actors perform solo on screen. “In the 1970s, I met Peter Berlin… a perfect Narcissus of Solo Sex practice. For years, the reclusive, blond, sylphlike Berlin has sold Solo Sex movies and videos of himself, shot by himself, featuring himself jerking off with/against himself on screen. Berlin has rarely shot another model, and has turned his own image, with his own camera, into an esthetically, and one hopes, financially successful cottage industry of mail-order Solo Sex. Peter Berlin, in…his tour-de-force films, Nights in Black Leather (1973) and That Boy (1974), is the perfect symbol of the high-flying Solo Sex Act of Man Alone, of Man as Island, of Man Sexually Self-Satisfied.”]

Jack Fritscher: Last night I re-watched all of Nights in Black Leather and That Boy.

Peter Berlin: You did? You did your homework.

Jack Fritscher: To. be prepared to chat with you. In my archives, there is my Peter Berlin folder. I must tell you how much I like Jim Tushinski’s documentary [That Man: Peter Berlin, 2005]. Perhaps this afternoon we can go beyond all those interviews and films to dig into something fresh about you — Armin — the artist at eighty who at twenty created his avatar Peter Berlin.

Peter Berlin: Right, right. People think they know Peter, but what they know is rarely about me, the person behind Peter. Peter Berlin is my stage name. [Armin Huene lives his life as an artist in pursuit of his muse who was Peter Berlin.] I’m a photographer, but I am not known like Robert Mapplethorpe or Marcus Leatherdale.

Jack Fritscher: May I say that just as there are now feature films about Mapplethorpe and Tom of Finland and Basquiat, there should be a Peter Berlin biopic.

Peter Berlin: There would have to be three actors playing me as a boy, as Peter Berlin, and then as the old man I am now.

Jack Fritscher: Have you seen Harry Styles in My Policeman? That movie has two actors playing the same character, one as young, one as old. And there’s Timothée Chalamet. He’s androgynous, award-winning, and a fashion icon who could channel the Peter Berlin Look.

Peter Berlin: I like Harry Styles. I think he could play Peter Berlin. While we talk, are you taking notes?

Jack Fritscher: Here at the beginning is where I ask your permission to record this.

Peter Berlin: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. I think this is a good thing. I wish I would be able to record it too. I wish I could have saved all my recorded phone messages I got over the years. I would love to have all the messages Mapplethorpe left in the 70s and 80s.

Jack Fritscher: Me too.

Peter Berlin: Did you make a lot of notes?

Jack Fritscher: I started keeping a journal when I was fourteen. From my journal notes in the 1970s, I wrote my novel Some Dance to Remember which is about the 1970s on Castro Street and Folsom.

Peter Berlin: I would encourage everybody to keep notes.

Jack Fritscher: I would too. Sam Steward kept his Stud File on every trick he ever had. Each on an index card.

Peter Berlin: I know about Sam. There’s a book, right?

Jack Fritscher: Justin Spring’s bio. It’s called Secret Historian. It too should be a feature film.

Peter Berlin: My friend Eric Smith gave me the book, but I don’t read much and I just sort of paged through it. But what I would give to have a Polaroid picture of all my tricks, thousands and thousands of tricks I had over the years.

Jack Fritscher: How many?

Peter Berlin: Thousands. Because I was — not to brag — collecting tricks. Sex was my thing. My photography was a sideshow.

Jack Fritscher: That’s the way we were. We were all like John Rechy collecting tricks aka “numbers” in his [1967] novel Numbers. Would you say 10,000?

Peter Berlin: I have to think about that. But at least 10,000. When I came out in the 60s, I had been living in Berlin for ten years, and going out every night. I was never looking for a relationship. I got off on getting people off. Sometimes without even touching. Just the idea of seeing a man standing opposite to me, existing in ecstasy. I could have maybe two, three, four men a night. I did that for ten years, twenty years, thirty years. I wish I would have a journal and could give you the number of 20,000.

Jack Fritscher: We’re all Rita Hayworth in Fire Down Below when she said, “Armies have marched over me.” I think our sex lives like our daily lives are essential, especially for those of us who rode the merry-go-round of that first decade after Stonewall.

Peter Berlin: That’s what I mean. Armies. I’m so glad that your timing and my timing of being born was brilliant. I was born in 1942.

Jack Fritscher: I agree. I was born in 1939. People today who didn’t live through the war and its aftermath, and the 60s and 70s may not understand that we were lucky to have met so many men so intimately.

Peter Berlin: The war in Germany.

Jack Fritscher: Right. My first memories are of that war. I was in grade school when it ended, and we all went downtown to celebrate in the streets. You and I are the unique generation of gay war babies.

Peter Berlin: I was too young to remember the war itself, but I think the 1920s and 30s must have been great in Berlin.

Jack Fritscher: Think of how much the wild Weimar Republic in the 1930s was like the 1970s.

Peter Berlin: Great in Hollywood too, right?

Jack Fritscher: Cabaret made the connection and with all its Academy Awards taught us something in the 1970s about Weimar bisexuality popular at places like Studio 54.

Peter Berlin: There was so much sexual freedom. Our time was really very special. Didn’t you think in those days after Stonewall that life would get better? Back then, I said, “Oh, this is really nice.” In my mind, in my fantasy, I always felt it could get even better. I thought the World War would be the last war ever. I was sure, first of all, that the Church would die out, all that nonsense about God and Jesus. Well! I was wrong in that — and I was wrong about things getting, [chuckles] you know, getting better. With AIDS and all. My grandmother was a Catholic, but my mother left the Church. When she was twelve, she asked a priest to explain the Immaculate Conception, and he said, “Marion, there are things we can’t explain,” and she said, “Okay, enough.”

Jack Fritscher: We were born lucky. We were very lucky to have been young and active in the window between the invention of penicillin and the arrival of HIV. We had great sex in a wonderful time. I also thought things were getting better during that time until Anita Bryant and AIDS and the politically correct raised their ugly heads.

Peter Berlin: I must explain I was never politically interested or active. When I came to America, I knew there was a war going on in, you know, the war…

Jack Fritscher: Vietnam.

Peter Berlin: Vietnam.

Jack Fritscher: Right. People forget that Vietnam dominated the 1970s. Men, including gay men, were still being drafted, some right off the streets of the Castro. Vietnam didn’t end till 1975 the year Drummer was founded.

Peter Berlin: I didn’t read the papers. I was always going out to have a good time. Anita Bryant, I read about her, but nothing of that affected me. See, when I came here I talked to younger guys, and heard the horror stories of being born in Texas, or being born into Catholic guilt. They had to get out because of gay bashing and religion. That never happened to me.

Jack Fritscher: So that American bigotry seemed like American fascism even to you who were born in Nazi-occupied Poland?

Peter Berlin: Yeah. Horrible. I was impressionable, but I was too young a boy to experience the Nazi occupation, but I remember the American occupation of Berlin.

Jack Fritscher: You were lucky. Tom of Finland was nineteen when the Nazis bombed Finland in 1939. He was born twenty years before us. He told me one night at supper, without flinching, that as a young man he was turned on by the uniforms of the Nazis who were occupying Finland. Look at his drawings. The fetish influence is there.

Peter Berlin: You see, I was protected. My poor mother, my poor dear mother, had three children. She had to flee from the Baltics to Berlin. Her husband, my father [1915-1945] died, was shot dead in the last days of the war [when Armin was three]. But me as a child? I was out playing in the sand in one of the big holes of a bomb, uh, you know, when a bomb, goes off, what is it?

Jack Fritscher: A crater?

Peter Berlin: Crater of a bomb. That’s where we were playing in Berlin. So, I just had a ball.

[To experience the context of the wrecked world of children playing in the rubble of postwar Berlin, see director Fred Zinnemann’s film, The Search (1948) shot on location in the city ruins, starring the beautiful gay Montgomery Clift and the marvelous Czechoslovakian child star Ivan Jandl who won a special Academy Award. Some of the film’s official screenings were hosted by the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.]

Peter Berlin: When I arrived in America, I was very surprised at how much drama people here in this country went through during the war.

Jack Fritscher: My first memories are of food and gas rationing. Nightly blackouts. Air raid wardens. Men leaving for the war. Women building tanks and bombs. Nothing compared to you, but until the war ended, I feared the Nazis and Tojo were going to kill me. My parents helped me a lot when we gathered up good pieces of our clothing, like my mother’s fur coat, and sent them off to displaced persons in “DP” camps, as we called them, in Germany.

Peter Berlin: I grew up okay about cops in Berlin. It was only when I arrived here and started cruising that I first had to run away from the police in the park.

Jack Fritscher: Right. In 1978, the San Francisco police raided my office at Drummer and tossed all our drawers and filing cabinets. Just like the Gestapo. Maybe you remember the night of the White Night Riot [May 21, 1979], the cops stormed the crowds on Castro Street and drove us down the street beating people with batons.

Peter Berlin: I knew about White Night. But Peter Berlin stayed outside of politics. I would only have read about it, right? It didn’t affect me, right? What’s the word in English? I sort of was unaware and not interested.

Jack Fritscher: Aloof, aloof.

[In the opening monologue of That Boy, the voice-over exposition is a thumbnail of what it was like to see Peter walking down the street. The narrator says about Peter: “I used to watch him on Polk Street everyday and wonder what he was looking at as he’d walk by a window [as if it were a mirror], stare into it, and leave. Parading down the street in his tight white pants showing off his huge organ of pleasure. Everyone would stare at him. Weird people. Boys. Girls. Young men. Freaks. Everyone staring at his cock. Doing anything to get attention. Still he ignored everyone….I suppose he knew they would follow him. Anywhere. Everywhere. Just to get one more look at his cock.”]

Jack Fritscher: In an age of San Francisco hippies, you were kind of like that other German, the Pied Piper of Hamlin, walking down Polk Street gathering up the Flower Children, but the pipe you played, displayed, was the most famous uncut cock of the 1970s.

Peter Berlin: [Laughs] Now I think I was then sort of a stupid person, just not aware of his surroundings.

Jack Fritscher: Armin! You were never a dizzy blond.

Peter Berlin: No, no. But I was sort of out of it. My father died because of politics. Lies and fake news. People would ask: “Do you know about this book or that film?” There was a person once at a party talking to me and he asked me, “Do you read?” And, I said, “No, I don’t read.” He looked at me and said he felt sorry for me. He said, “In school in Germany you had to read, right?” Reading was part of my education, but I didn’t read. I was so, so visual. That was a big negative for that person.

Jack Fritscher: John Waters says if you go home with a guy and he has no books, don’t fuck him.

Peter Berlin: Let me tell you. As an artist from postwar Germany, I was tired of politics that ruined everything.

Jack Fritscher: Politics can cause PTSD.

Peter Berlin: I wasn’t politically active. I knew there was a Harvey Milk — and could have cared less. I didn’t vote for him or anyone else. I wasn’t trying to change things in San Francisco. I was changing myself in America.

Jack Fritscher: Inventing your self?

Peter Berlin: Inventing Peter Berlin.

Jack Fritscher: Your performance art. Your street theater. You were a rebel whose cause was knowing your self.

Peter Berlin: My days were spent at the beach, at Land’s End [at the west end of Golden Gate Park], oiled up, and looking good, and high. Okay? I saw I could create attention. So when I went home, I said, “Okay, take a camera and make a picture.” I tried to capture the image I was creating. That was my life. That’s so completely different from Mapplethorpe and Leatherdale who were trying to achieve their own certain vision, especially Robert, and all the other photographers who saw their photography as a career to be successful and make money. I never had money in my mind. That’s why I’m poor.

Jack Fritscher: It’s hard to make money from art.

Peter Berlin: With all the books you’ve written, you couldn’t live on those?

Jack Fritscher: Oh, no, no, no. My God, no. As a gay writer for sixty years, I’ve earned about a penny a day. If that. Some books take ten years. Plus since the internet started [1995], I’ve posted my books free to all online. Like you, I don’t create for money. I write to document gay experiences. Even while I edited Drummer on the side for three years, I’ve always had a straight job. So on weekend afternoons I’d see you cruising Polk Street, and as a writer, I’d observe you from afar because your act was too fascinating to interrupt.

[When Peter strolled down Polkstrasse in 1972, even before releasing his first film which would have made a great music video, I could hear Lou Reed singing his new song, “Walk on the Wild Side.” When people mention a sighting of Peter Berlin, they always remember where and when they first saw him on the street — and what they thought. Like a Hollywood star, Peter’s hand, foot, and dick prints should be cast in the cement in front of what’s left of the Alhambra Theater on Polk Street.]

Jack Fritscher: I liked watching you — just like the guy you cast as a character, the voyeur, watching you, the exhibitionist, from across that Polk Street intersection in That Boy. I studied you because I was taking mental notes of the rise of Polk Street and Castro Street and Folsom Street.

Peter Berlin: In my documentary [That Man], Armistead [Maupin, author of Tales of the City] said he saw me at the beach and he came up to me and said that he figured that, like him, I didn’t want to be approached and have to talk to so many people and hear them saying things repeated over the years. “I saw you on Polk Street,” or “I saw you in Provincetown,” or “I saw you in New York,” you know, always from afar, because that was my thing. [Four minutes into Nights in Black Leather, Peter talks on screen about these kinds of fan questions.] To save my privacy in public which was Peter Berlin’s stage, I gave the impression: “Please don’t come up and try to talk to me.”

Jack Fritscher: You are Armin. They wanted to talk to Peter. I never approached you then because I dug your vibe. I thought of you as the Gay Garbo. I would no more have talked to you while you were performing “Peter” than I would’ve talked to an actor on a Broadway stage.

Peter Berlin: Now, looking back, I like saying, “I played the role of Peter Berlin.”

Jack Fritscher: Yes.

Peter Berlin: And I played it very well. Right? It was like I was on stage. And the people who realize that, like you, said, “Okay, that’s what he’s doing. So I’ll just watch him.”

Jack Fritscher: I saw what you had to offer in your tight clothes and your Saran Wrap white tights [which, according to the New York Times, inspired Freddie Mercury to “shrink-wrap his junk.”] I appreciated your exhibitionism. Your show on the road. I went on my way thinking how well you captured your street image and distilled it into all the pictures and ads you ran in papers and magazines to sell your movies.

Peter Berlin: There was not one political thing in my films.

Jack Fritscher: That’s radical. Has any gay filmmaker ever said that? Your movies, like Leni Riefenstahl’s, were about beauty which transcends politics.

Peter Berlin: Whenever people talk to me about my films, I always say they’re nothing to write home about. Now, years later, I’d love to re-edit the films to make them better.

Jack Fritscher: As I told you, last night for the second time in fifty years, I watched both of your movies, Black Leather and That Boy, and really enjoyed them both.

Peter Berlin: So you prepared yourself.

Jack Fritscher: Of course. Out of respect. I’ve been preparing for you for three days. I’ve got five pages of notes to ask you.

Peter Berlin: I’m so flattered because, you know, back when you published that Drummer article on Tom of Finland, I always felt that I was not included as part of that Drummer leather art scene.

Jack Fritscher: No, you weren’t. You were thought of, and then purposely excluded. At first, homomasculine leathermen did not know what to make of your leatherish androgyny. When I interviewed the director Roger Earl [in 1997], he told me on the record that when he was casting Born to Raise Hell in 1975, he thought “Peter Berlin would be perfect as the lead.” But the producer [Terry LeGrand] wanted a more standard-looking leatherman like Ledermeister, the brawny hairy Colt model who was the lifelong erotic avatar of San Francisco actor Paul Garrior. Paul looked the part, but he was not really a leather player. So they cast Val Martin, our first “Mr. Drummer,” a leatherman immigrant from Argentina, in the role you would have played. Like us, Ledermeister, who just died, lived into his eighties, but Val died young of AIDS.

[The Peter Berlin character is a vivid example that gender is construction and performance. In Drummer 66, July 1983, when Peter got his only mention on the contents page, the shameless publisher John Embry reductively compared Peter to the campy Chippendale dancers.]

Peter Berlin: I did not know all those details, but being directed by someone else? Ugh. So difficult in my first film. I always felt I was not into that “Leather Thing” even though I wore some of it. I was not part of the so-called fetish scene because I was shy, and I didn’t want all that “leather fraternity” stuff of parties and dinners and orgies. I only wanted to get laid.

Jack Fritscher: Like Erica Jong, you were in search of a zipless fuck.

Peter Berlin: What’s that?

Jack Fritscher: Casual, spontaneous, anonymous sex with strangers.

Peter Berlin: Exactly.

Jack Fritscher: So, instead, you played at the baths, like the Barracks on Folsom, to get your kink on?

Peter Berlin: The Barracks? I loved it. There was the [Red Star Saloon] bar downstairs, and then behind it and upstairs the Barracks bathhouse. It was the best.

Jack Fritscher: I agree. [Leather poet] Thom Gunn wrote lyrics about it. I spent hundreds of nights and weekends there. Room 326. First door left top of stairs.

Peter Berlin: I liked to go to the Barracks after cruising the streets after the bars closed.

Jack Fritscher: The Barracks had a lot of rough and creative S&M action, hundreds of men orgying in pig piles, but it wasn’t solely leather because the Barracks was a kind of three-story theater with lots of exhibitionists and lots of voyeurs. It was a three-ring circus. You didn’t have to play S&M games or even touch anyone to have a good time.

Peter Berlin: You’re right. I liked walking up and down the hallways and posing under one of the spotlights at ends of the halls. Men who like looking liked my exhibitionism.

Jack Fritscher: Peter Berlin was obvious, obscene, and hot. You were your own art exhibit, a voyeur’s dream.

Peter Berlin: I didn’t get involved like Mapplethorpe did.

Jack Fritscher: Peter Berlin never shoved a whip up his ass.

Peter Berlin: I heard about the games Robert played from my friend, Jochen Labriola [1942-1988, German-American painter]. Jochen was an artist and my best friend and my patron in those days. I never had to work again. Thanks to him. He taught me how to paint. He was the one who actually got me out of Germany — and that’s why I ended up in America. Jochen had a fling with Robert, and told me, uh, how you sometimes sit and say, “Oh, you know, uh, the games Robert was playing.” His trips were never, never my thing. You see, I met Robert when he approached me because I was Peter Berlin. He liked my fame.

Jack Fritscher: He introduced himself to me because I was the editor-in-chief of Drummer and he needed publicity.

Peter Berlin: He was always very impressed that people recognized me, and he liked that. So I only know Robert from talking and hanging out with him, but I never had sex with him. It never occurred to me that I even wanted it. Right? The same with Marcus Leatherdale. You know, one thing that really surprised me in the Mapplethorpe [HBO] documentary was when you read into the camera the letter Robert wrote to you about Leatherdale — that he found Marcus basically naive. That surprised me.

[On September 12, 1978, Robert wrote me a letter complaining about some wannabe who was bugging him. “The ‘punk’ leather boy from San Francisco is getting more and more on my nerves. I hate naïve people. He just left wearing his motorcycle jacket. I feel as though he shouldn’t be allowed to wear it as he just doesn’t have a sophisticated sense of sex. I hate happy, naïve people.” I never asked Robert the guy’s name. I didn’t pry. I never knew who he was. However, in 2015 when Randy Barbato and Fenton Bailey came to my home to interview me for Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures, I read into their camera several letters Robert had written to me, including the one about the troublesome punk leather guy. Creating a perfect made-for-TV moment, the genius directors, the producers of RuPaul’s Drag Race, who know their business shot a close-up of Marcus Leatherdale while they played for him the recording of me reading Robert’s letter. It hit him like a punch in the face. I felt sorry for him caught on camera. Had I known the unnamed guy was identifiable and alive, I would never have read the letter out loud. I debated over and over about contacting him and apologizing for the weird concurrence, but I didn’t want to make matters worse because he may not have known that it was my voice reading the letter. And why bring up a sore subject with someone I never met? After having a stroke in 2021, he committed suicide in 2022.]

Jack Fritscher: Well, they kissed and made up after he wrote that letter to me.

Peter Berlin: Then they hung out for quite a while, huh?

Jack Fritscher: They did. They ran around Manhattan like twin boyfriends. Robert hired Marcus to work as an office manager in his studio. And then competition reared its head.

Peter Berlin: Because they both were photographers.

Jack Fritscher: Some say they were fighting over models. Marcus beat Robert to Madonna. And Leatherdale’s photographs often looked too much like Mapplethorpe pictures, plus Robert, you know, in the early 80s was moving away from white guys to black guys.

Peter Berlin: I remember Robert telling me he only had sex with black guys.

Jack Fritscher: Robert had an interracial eye even as a student at Pratt that evolved while he and I were romantically involved in the late1970s. In the 1980s, he turned from white guys to black men on and off camera.

Peter Berlin: When I was in his loft [24 Bond Street], he showed me some of his pictures. The Warhol portrait of him was hanging on the wall, right? And the cocaine was always there. So I asked, “Robert, no more nice white guys?” He said, “No, only black guys.” It sort of surprised me. “Over the years,” he said, “I realized I basically was attracted to black guys.” I also realized there’s something about black men or the black soul, not only beautiful, but there’s something so, so, authentic. I’ve had two black roommates, one several years ago, Bryce White, who had been in jail, and one now, Reggie. I think of the bodies of those guys. White guys can go to the gym for twenty years and will never will look like this black perfection.

Jack Fritscher: Race, sex, gender. Welcome to America. Can you tell me about your father? I know you were only three, but can you describe the postwar Berlin scene growing up fatherless, what you and your mother felt, what your mother later told you about the last days of the war when he was shot dead?

Peter Berlin: One of his comrades who was with him when he died told us that at that time the Wehrmacht was rationing guns and ammunition, and sending unarmed soldiers who had no protection to the Eastern Front.

Jack Fritscher: Like Putin in Ukraine.

Peter Berlin: Yes. Like Putin. So my father was in the situation where the Russians were close, but he was unarmed. He was a sitting duck and he was shot dead. My mother only knew it because, at some point, she got a postcard from Dr. Weiss, a soldier who was a doctor, but she never got any sort of confirmation from the German government. My father was about thirty years old when he died.

Jack Fritscher: Was he drafted into the German army?

[A number of gay men in the U.S. in the 1970s had escaped Nazi Germany after being forcibly ordered as Hitler Youth to the Eastern Front in the last days of the war. As fourteen and fifteen year-old boys, like Hank Diethelm, the jolly immigrant owner of the Brig leather bar on Folsom Street in San Francisco, they disobeyed the order, ditched their uniforms, and fled West into the arms of Allied troops who rescued the teen boys, and brought them to the U.S. In a tragic irony of murder on April 10, 1983, Hank who — to deal with his postwar PTSD had made a counterphobic sex fetish of Nazi S&M — was tied up, tortured, and strangled in a dentist’s chair in the basement playroom of his home where his body was set on fire destroying his house.]

Peter Berlin: Yes. He had to go to war. I was a baby. Because I have no memory of that time, just before my mother died two years ago, I asked her to write what happened in his last days. You remember that they tried to kill Hitler with a suitcase bomb under his desk, but he survived, When my father heard that, he got so upset. “How could you,” you know, “kill the Führer?” He believed the propaganda they were fighting for the fatherland. And then in the last letters my mother got from him, he started to suddenly realize what was happening. You see this idea when the Germans say they didn’t understand what was happening. There was truth to it. I was born in Litzmannstadt, Poland, while it was occupied by Hitler, and what I even didn’t know, there was a concentration camp. Right? In Litzmannstadt. Right? I had no idea. I only know my mother told me one day years later, “Do you know that one of the inmates escaped from the concentration camp and knocked on our door and asked for help?” And my father gave him a horse to get away and he said, “I can’t do more because it’s too dangerous for my family. I could get killed.” I mean, all these stories, what my mother told me, so awful. Maybe that’s why I’m not so much interested in my own history.

Jack Fritscher: So your father as a young man was swept up into the politics of the times and believed the fake news until he realized what he believed was not happening.

Peter Berlin: Like me, he was not very much following the nitty-gritty of politics. So I’d like to think he knew nothing about the killing of the Jews. I know that my Hoyningen-Huene family is a big tribe. Still is. I had one cousin who was a very big Nazi. My mother said when he was at our dinner table that he spent time criticizing her for being too, um, yeah, too beautiful and too sexy, you know? And she told him, “Shut the fuck up. I know who you are.”

Jack Fritscher: A Nazi relative at a dinner table? Worse than a crazy MAGA uncle at Thanksgiving. Your mother was not a Nazi.

Peter Berlin: No. In the circle of my parents’ and grandparents’ friends, there were so many Jewish people. I only knew their names. I had no idea who was a Jew or not a Jew. Later on, I was thankful that my family had no feelings of antisemitism, just like I’m color blind about race.

Jack Fritscher: Yeah. One might think your father didn’t read and consequences killed him.

Peter Berlin: I know. My father was a Landwirt, a farmer. We had land. I have pictures. We raised horses and pigs. He was just a country boy when he came from the farm and met my mother in Berlin. I remember her telling me the first thing she thought was, “Oh, he’s so arrogant.” But he had that Hoyningen-Huene name and there was a title and this and that, you know. So they married and she was widowed, and she and I and my brother and sister fled to Berlin where I grew up and came out while the East Germans [under Soviet Russia] were building the Berlin Wall.

Jack Fritscher: You were outed the day they started building the Berlin Wall? Yes? [Sunday, 13 August 1961]

Peter Berlin: No, I was out already. I had just come out. I was nineteen. But my mother didn’t get it. It was a weekend, just another gay weekend, with all the East German boys coming over to West Berlin because that’s where the fun was, and the clubs. I was picked up on a Saturday night by an East German guy and he took me home to East Germany. To East Berlin. Right? And the next day when I wanted to go back, the S-Bahn train we’d crossed over on was not running. I realized the trains were not going. I said, “What’s happening? What’s happening?” So I remember I had to walk back home passing through the Brandenburg Gate where I saw what were now East German soldiers rolling out this wire fencing thing, and I just stepped over it from East Berlin to West Berlin. And then I realized what was happening.

The reason I was outed that weekend when this all happened was because it was in the television news. Everybody understood the danger of what was happening. My mother realized: “Oh, Armin is not here. Where’s Armin?” Right? And then I, yeah, was, yeah, outed. To her.

Jack Fritscher: Like your father, you were swept up into history. How were you outed?

Peter Berlin: Like I said, I was out before, but I always was very private. I never said anything. I seemed only a little bit out of the norm because of the way I dressed in tight pants I ran up on a sewing machine. Because I was gone all night in East Berlin, and because the news of the Wall was so frightening, my mother worried herself into a state. She asked me where I was, what I was doing. I was never into lying or anything, you know. And I never felt, “Oh, my God, I do something wrong.” So right then I came right out with it. I came out to her because of the televison news. I said to her “This is what I do.” She was horrified because homosexuality was something basically sick. My dear mother didn’t understand. My whole family didn’t understand. Then I found out my mother had found a letter I’d written about sex. All that happened on one day. I had to move out of my home and I was happy to move out to a rooming house. I finally felt very free, right? But then afterwards, my mother and my family adjusted. My sister had a lot of gay friends. My nephews, I have three of them, are now grown men who are completely good with it, right? But they are all straight. My nephew Martin always said he was very proud of me because every family needs a black sheep.

Jack Fritscher: Was your trick in East Berlin young or older?

Peter Berlin: No, no, no, no. I went with German boys. Young. I never went with older men. I never looked for older men. I never looked for my daddy. I’ve always looked for my age and younger.

[In scenes in That Man, Peter has sex with the types of young black and blond ephebes he prefers. His contemporary Fred Halsted also romanced chicken born yesterday in his lover Joey Yale, his blond co-star in LA Plays Itself and Sextool, for whom writer-director Halsted said he coined the term twink.]

Peter Berlin: I remember everybody seemed over twenty when I was seventeen — already too old for me, right? So that trick from East Berlin was my age. A teenager. He was nineteen. I remember he wore a suit which was never my cup of tea. But somehow we hooked up and we went to his place in East Berlin.

Jack Fritscher: Now I understand how it happened when your mother asked, “Where’s Armin?”

Peter Berlin: Unfortunately, my exact memory fails me. I only remember my mother looking at me with disgust, you know? Because she looked at my tight pants and she was horrified. I completely understood that. I never, never, never had one negative thought about my mother, or my misguided stepfather. I realized at that moment that some people don’t understand things. And one can’t blame them for that. And I never blamed my mother. I never blamed my stepfather. She was a very traditional woman in those days. Now she’s dead I can say this. She only had three men — compared to you and me. My father was her first. Years later, she admitted, “Oh, once at a party there was this beautiful man.” Later she said, “Oh, my god, I should have.”

Not long after my father died, she met Herr Kittel, my stepfather, a sort of a typical German. But nice, you know. I always had a good time with him. After the war, he moved in and was trying to make a living for us. He started to work for Daimler Benz, the Mercedes Benz company. And he worked himself up to a very good position and was a bit bourgeois which embarrassed my mother a little bit because he was always kind of showing off. My family is from a very aristocratic background. We never talked about money. That was something one just doesn’t discuss.

Jack Fritscher: So he was your mother’s live-in lover.

Peter Berlin: He thought that the man was the boss and the woman was in the kitchen. But my mother considered us lucky. She said, “My God, he stood by me and took on three little children.” My mother always felt grateful because survival was very hard at that time. We had lost everything.

Jack Fritscher: So, Herr Kittel lived with your mother and you and your two siblings?

Peter Berlin: Yeah. At some point, he moved in with us when we lived with my grandmother who never accepted Herr Kittel. My grandmother was this woman who behaved like a queen. She wasn’t bad, but she believed the servants were downstairs and we Hoyningen-Huene were upstairs. Is upstairs right? There was that feeling Herr Kittel is not one of us. There was always that thing about class. Now, you see, now I can talk about it openly. My mother is dead. Herr Kittel is dead. I always saw him from the outside, but I always felt good with Herr Kittel. When we were children, he helped us build little toys, like a little sailing boat. He took time for us and I always felt good. My sister’s completely different because she felt completely negative about him, and that made life very difficult for my poor mother. My mother was always caught in between the two. She had to appease my sister and she had to appease him. I always felt sorry for my poor mother who worked so hard to feed us and keep us together.

Jack Fritscher: The grandmother you lived with. Was she born in Russia?

Peter Berlin: In Saint Petersburg. On the Baltic Sea. She spoke fluent Russian and she loved the Russians. See, this is the trouble. We think of Russia today as the enemy because that idiot Putin has made it so terrible now with his invasion of Ukraine. The Russian people are good, the way the people of any nation are good, until politics ruins them. Are American people bad because of what’s now happening here in America with the percentage of right-wing nuts who are running the show?

Jack Fritscher: Right.

Peter Berlin: Americans mostly are good to Germans. German people are nice people, But back then there were some before the war who said, “Okay, let’s find some scapegoat for our troubles. Let’s find a scapegoat for the economy. Somebody has to pay.” The Jews had to pay. I remember when my mother was hiding a Jewish man and woman who were our friends. I know about this from my mother’s stories. She wrote so much beautiful stuff. All in German.

Jack Fritscher: She kept notes.

Peter Berlin: Yes. I’ve always had the idea of writing my autobiography. I have her writings. My family story is actually a very, very good story about my upbringing and my family. What I was like during the first part of my life before the second part of my life: the Peter Berlin thing. And the third part, me as Armin who is an old man, right? The old man telling the story.

Jack Fritscher: The Lion in Winter.

Peter Berlin: I always said, “Oh, my God, I wish I had money.” I could make a film with the best talent of Hollywood. There’s a German guy, a musician who writes film music. Hans Zimmer. I would hire people like him. Academy Award winners. I’d put out a casting call for some actor to play Peter Berlin. I can’t think of one famous young person who could play me. I think it would be an unknown.

Jack Fritscher: We’ve mentioned Harry Styles who is famous, talented, and still young.

Peter Berlin: Yes. If a film were made, the actor playing Peter Berlin in the 1970s would become a star, or an even bigger star. He’d be one of three actors playing Armin as a boy, Peter Berlin as a young man, and then me as the old storyteller. Only I can tell you movie scenes that are real like one time in Paris I saw a beautiful man in a shop window and thought “Look at that guy!” Then realized it was me. It was like a shot of me on screen. I had found one of my dream lovers. Me. I wish it had been someone else. I would have liked to have met him. My other dream lover is a robot. My camera.

[In the first two minutes of Peter’s first movie, That Boy, Peter’s star face debuted on screen in a mirror like the introduction of Barbra Streisand’s star face in a mirror at the beginning of Funny Girl. It’s not narcissism. It a human moment of spring awakening when a young man first truly sees himself. With Pachelbel’s Canon in D playing on the soundtrack, Peter identifies himself as a satyr among the wood nymphs. The opening edenic garden-park scene is his “Afternoon of a Faun” sequence.]

Peter Berlin: A Hollywood movie of me is a dream that will never be realized. It would be the crowning glory of my life. I’m losing my memory. I’m ready to go. I had my life and I’d just like to go to sleep and not wake up. But I think that my double life as a person and as the persona of Peter Berlin would make an interesting movie digging into the essence of Peter Berlin who is a very in-your-face erotic character, like the Tom of Finland characters.

Jack Fritscher: What did you think of the Tom of Finland movie?

Peter Berlin: I loved it. I was impressed by its production values. I would have to watch it again. It seemed authentic. I wish there was less emphasis on the war scenes and killing than there was on scenes revealing the soul of what I felt Tom the person was. I really must watch it again. I liked the production, but I would have done it a little different. I always look at any film now as a filmmaker, as an editor. When I was a child, I watched movies for the story. As a filmmaker, I look at movies from a different perspective. Is the Tom movie still playing?

Jack Fritscher: It’s streaming online.

[All comparisons are odious especially when it comes to Origin Stories, but I think the lavender roots of a common gay history call for some comparison, contrast, and consideration of the interlocutory DNA of the generational and geographical male gaze. Tom of Finland (born 1920) and Peter Berlin (born 1942) were European artists working at the same time in the 1960s and 1970s. With a head start in the 1920s, Tom in Finland was in his forties and in print when Armin in his twenties in Germany in the 1960s began creating Peter Berlin. It’s as if both visionary artists were coincidentally drinking from the same homomasculine well. So many of Tom’s drawings of men in tight pants, cocks rampant, legs spread, torsos angled, resemble Peter’s poses in his photos. Both artists may object, but it’s as if two men — like two generations of older and younger leather brothers — dialed into the same European homomasculine archetype and each made that platonic ideal of gay masculinity uniquely his own. Tom drew men like Peter posed, and Peter posed like men Tom drew. You say Tomato. I say Toronto. One’s critical thinking must not make the logical fallacy, “Post hoc, ergo propter hoc,” that because B follows A, B must have been caused by A .Armin said his life and work are simply “coincidental” with Tom’s.

Queer scholarship has yet to notice that the artist whose 1970s drawings also resembled Peter Berlin and his look was Frederick L. “Toby” Bluth (July 11, 1940-October 31, 2013). He whose porn signature was “Toby” was a longtime and very important Walt Disney artist and stage producer who also had a gay underground career creating in 1970 his sexy-go-lucky cartoon drawings of his young blond avatar, “Toby,” his own platonic ideal of a juicy teen piece of veal, not yet beef, with Dutch Boy blond hair, a button nose, a bubble butt, and a big cock.

Even though gay scholars have yet to notice the zeitgeist connection between Berlin and Bluth, the “Toby” drawings were everywhere in the gay press from The Advocate to After Dark because “Toby,” whose succulent flesh looked pumped with sperm was the dripping epitome of the “young, dumb, and full of cum” blond look that dominated gay vanilla culture before grown men yanked the gay gaze from ephebes toward adult men in leather like Peter Berlin. Just so, those two magazines that liked “Toby” were the first publications to pay important media attention to Peter Berlin.

If ever any artist might have created a series of animation cells to present the Cartoon Adventures of Peter Berlin, it would have been Bluth who knew a thing or two at Disney about creating animated characters. While not cartoons, Tom of Finland’s selected storyboard drawings also seem ready-made to be rounded up, maybe by artificial intelligence, to illustrate a curated graphic novel about Peter Berlin and his leather pals the way Tom created his Kake series of comic books.

For one of its ads appealing for subscriptions, The Advocate, skimming close to the popular Peter Berlin look, used a drawing of “Toby” reclined like a satyr in a field of flowers and butterflies (like Peter in the opening of Nights in Black Leather), stripped to the waist, pecs ahoy, wearing fringed bellbottoms, a cocked knee hiding a promised hardon. In the way that Peter Berlin of San Francisco advertised himself and his films insistently in the gay press, Toby of Los Angeles was also the come-and-get-it advertising image for businesses like the Key Club baths, the Fallen Angel bar, the Closet bar, the Coronet Theater, the Metropolitan Community Church, and the musical, “Love: As You Like It, A Male Musical. Shakespeare Transmogrified by TOBY. Previews start April 12, 1972. [At that time, Peter was shooting Nights in Black Leather.] Tiffany Theater, 8534 Sunset Strip. All Male Cast of 25. Limited to L.A. run prior to S. F. and N. Y.”

One can only wonder what kind of erotic convergence might have exploded on stage if Peter Berlin had auditioned for director Toby/Bluth to be cast in the role of Jaques for whom “All the world’s a stage.” Just like Polk Street.

“I never wanted to be on stage,” Peter told me, “even if I could sing and dance. I wouldn’t want to be that kind of product in front of a crowd. Peter Berlin only had one admirer at a time. Even two people would be too much.”]

Peter Berlin: In the late 1970s [1978], I approached Tom who was signing books in a San Francisco store. Tom said, “Hello,” but he was distracted, like, he didn’t say, “Oh, my God, Peter Berlin,” or anything like that. He was kind of cold. I wasn’t a collector of his work, but I liked the idea of having a Tom of Finland original. The meeting was not an earthshaking encounter. He said yes, he’d draw me. So I sent him photos and he made four drawings of me at $300 a piece.

[Ultimately, Tom of Finland drew Peter six times. After the first commercial meeting in 1978, Tom on his own dime went on to draw Peter Berlin and Jochen Labriola as two cruising studs walking together down the street. The MOMA exhibited the drawing. About Jochen, Peter said: “There’s a German word: comrade; it can mean friend or lover. It doesn’t necessarily have to do with sex, just great fun, great humor, great understanding. When Jochen died, my life went from color to black and white.”]

Jack Fritscher: I have a clipping here I’d like to share with you. John Waters, who often works the same pop-culture beat as I, wrote in The New York Times Style Magazine that “Peter Berlin, Kenneth Anger, Joe Dallesandro, Jeff Stryker, Jim Morrison, James Bidgood, John Rechy, even Elvis and James Dean. None of them could have existed without Tom of Finland’s art coming first.”

Peter Berlin: John Waters is an interesting man, but this comment is stupid and inaccurate. If I had never seen a drawing by Tom of Finland, I’d still have become Peter Berlin. I see myself as the living expression of Tom’s fantasy, but he did not create me. Tom created drawings. I created a live person. We were sort of coincidental. Tom is a good artist. Don’t get me wrong. I like his work, and I like the Tom of Finland Foundation and Durk Dehner, but if Durk with his business head had not decided to become Tom’s champion and turn him into a Foundation [in 1984], his drawings would never have moved from the small sex magazines to galleries and museums. Durk broke the porn ceiling and got him in museums.

[Tom of Finland and Peter Berlin, each in his own way, like the iconic fashion designer RoB of Amsterdam, were, alongside the power of Drummer magazine, the first “influencers” who helped create international leather culture.]

Jack Fritscher: Does resembling Tom’s men mean cause and effect or common sources? From before Tom and you hit it big in pop culture, gay leathermen cloning their image in the first leather bars in the 50s stood, posed, and dressed like straight 1940s bike gangs [Hollister] and 1960s biker movies after Brando and James Dean defined leather posturing in The Wild One [1953] and Rebel without a Cause [1955].

Peter Berlin: That all took awhile.

Jack Fritscher: Actually, when I was editor and at odds with the publisher, I managed to publish Tom’s work as a Drummer first for Tom in my special arts issue called Son of Drummer [September 1978 featuring Tom and Mapplethorpe and the leather artist Rex].

[Because publisher John Embry had a black list that included Tom for demanding payment for his work, Tom wasn’t even mentioned again after my 1978 notice until four years later in Drummer 61, February 1982. After Embry sold Drummer to Anthony DeBlase in 1986, it took six years from that 1982 mention — and four years after Durk started the Foundation — for Tom to be published in Drummer on the cover of issue 113, February 1988].

Jack Fritscher: I watched your two films online. Your long and short films are very popular with lots of late-night hits on pornsites. Thousands of viewers watching for free just like I watched Nights in Black Leather.

Peter Berlin: Then I will watch it again. This is the problem with me. My memory was always bad. It’s not the recreational drugs we all took. I remember in school for English lessons, the teacher was reading a story and writing new vocabulary words on the blackboard so we could all repeat them over and over. I had to make little notes to keep up. The same with mathematics. In English and mathematics, you have to remember the rules. Reading and writing were always so hard for me. That’s why I asked you, “Did you make any notes?” I wish I would have written a diary or shot little Polaroids of all their faces.

Jack Fritscher: Like Mapplethorpe shot Polaroids of you.

Peter Berlin: Yes, because I have very few clear images in my mind of the thousands of boys I had. I do have lot of notes I wrote when I was stoned at the beach, oiled up, early in the morning when it was quiet. I was usually the first one there. And then I had my little “garage marijuana” to smoke and that always helped me focus my mind. Grass is fantastic, right? I don’t do grass anymore.

Jack Fritscher: In pursuit of the origin of Peter Berlin, may we return to your family DNA in Saint Petersburg out of whose “Peter” maybe subliminally came your “Peter” Berlin — the way your famous relative, George Hoyningen-Huene [1900-1968] came out of the Russian Revolution and became Chief of Photography of French Vogue [in the 1920s before meeting, in 1930, fashion photographer Horst P. Horst who was both his lover and model].

Peter Berlin: Many of the Germans living in Russia, like my grandfather, were working for the Tsar who hired German aristocrats to teach upper-class manners to Russian aristocrats.

[The Tsarina Alexandra was a German princess who married Tsar Nicholas in 1894 and ran a German-inflected Imperial Court until they were murdered during the Russian Revolution in 1918.]

Jack Fritscher: How did your family become aristocratic? How did you get the baron title?

Peter Berlin: My family tree goes back to 1500 or so. It’s a German title given by the König [king], and then passed to each generation. You inherit it. That all stopped in 1918 [with the fall of the German Empire at the end for the First World War].

Jack Fritscher: Was your father a baron?

Peter Berlin: Yes.

Jack Fritscher: Are you a baron?

Peter Berlin: Yeah. But it’s no longer a title. Barons no longer exist, but the title became part of the name. My cousin in Berlin, who is old and sick, said she always felt like, “Yes! I’m a Baronin, a baroness.” She married a scientist who was an earthquake expert, but she didn’t take his name. She was always the Baroness von Hoyningen-Huene. I deleted myself from all that. I like that Touko [Laaksonen] called himself “Tom of Finland,” but I purposely called myself “Peter Berlin,” not “Peter of Berlin.”

Jack Fritscher: Good branding.

Peter Berlin: So, the von and the baron, I never used because I never think in those royal terms, although I do, as myself Armin, appreciate certain behavior towards me, where I feel that somebody should give me respect. Maybe that’s because when I was Peter Berlin, I was treated like a dumb blond. “Oh, he must be stupid!” So I’d immediately put the brakes on, and sometimes offended people who thought Peter Berlin was an arrogant asshole.

Jack Fritscher: Do you think that Peter Berlin is an extension of the baron? Is Peter Berlin more aristocratic than Armin?

Peter Berlin: Yes. Unlike little me, Peter Berlin has a commanding presence. The image I created is a very stylized expression of male masculinity without being overly butch. I’m not really a hardcore leather guy, right? Peter Berlin has always straddled a certain androgynous quality. He has gay and straight appeal. I have now a woman in my life. She’s from Canada. She wrote to me after she saw my documentary. What was surprising, she thought, looking at my picture, that I was straight. Okay. On one hand, I look gay. On the other, straight. Art is in the eye of the beholder. I’m not any of those labels, those boxes, gay, straight, up and down, black and white. I don’t go there because labels are just a made-up thing to put people in their place. I like the idea of straight appearance, you know? I just do. About homosexuality, I had so much to think about because homosexuality is so completely misunderstood in our stupid society. I think there is, I don’t know, was it Mr. Jung said about some kind of scale, you know, really gay or really straight?

Jack Fritscher: The Kinsey Scale?

Peter Berlin: Yeah, Kinsey. Not Jung. You see my memory? Thank God, you know, I am definitely, definitely, definitely gay. I’ve never had an experience with a woman. It wouldn’t even occur to me.

Jack Fritscher: We’re Gold Star Gays.

Peter Berlin: Many of my friends have had experiences with a woman, and I say, “Rah! Rah! Rah!” because they all stayed gay. I did consider women. Why in the world do I eliminate half of the population? Wouldn’t it be more intelligent to have sex with boys and girls? But I made my decision. It’s not gender so much as beauty. I’m such a great admirer of male beauty and beautiful men. That word beauty is very important to me because it’s a free word. Like art. You don’t find it in the American Constitution, in no law book. It’s really only in poetry. I always felt that beautiful people have different laws. Think about that.

Jack Fritscher: I have. I’ve lived it. I wrote a novel about the privilege of the bad and the beautiful in San Francisco. Beautiful men think they can get away with murder and your checkbook and your heart.

Peter Berlin: Romeo and Juliet never interested me because of Juliet. Love between a man and woman was not interesting to me as a boy. Nowadays homosexuality is really a mainstream thing on screen. Still there is no Hollywood movie of Peter Berlin who, it makes perfect sense, is still mysteriously taboo, like when my mother looked at me with genuine disgust. Magazines still censor my frontal nude shots.

Jack Fritscher: The most frightening thing in the world is a photo of a penis. Ask Mapplethorpe.

Peter Berlin: I’m constantly shocked when I see nasty news about gays in the political arena. I’m shocked. I’m shocked. A shock should only last split seconds, but when I’m shocked for three days, I say, “Oh, fuck you.” Peter Berlin not fitting into that world makes perfect sense. So I don’t go out. I live very much private. Like you, right?

Jack Fritscher: San Francisco is for the young. I retired to the woods north of the Golden Gate.

Peter Berlin: When I read your book on Mapplethorpe [1994] describing the whole scene of New York and Studio 54 and the Mineshaft in the 1970s, it seems now just like a dream, no?

[I think it’s almost impossible for anyone who did not experience the 1970s to understand how wild was that first decade after Stonewall. In 1975, the year Drummer began publication to report on the rising new gay leather culture, New York City was a 24/7 sex party celebrating the “divine decadence” of Cabaret (1972) with thousands of newly liberated men coming from around the world to cruise streets, bars, baths, piers, parks, and clubs like Studio 54 and the Mineshaft. As we rose to heights of gay sex not seen since orgies in ancient Rome, we creatures of the night — unlike politically correct gay puritan censors, like Richard Goldstein condemning leather culture as akin to Nazism in the Village Voice in 1975 — did not care that Manhattan was a dangerous bankrupt garbage dump where we felt safe and encouraged because the city was as lawless as the wild west and every cowboy knew the lyrics to “Anything Goes.” The blighted urban context we had to walk through to get to our pleasure domes shows up in its full glory in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver and William Friedkin’s Cruising.]

Jack Fritscher: Oh, yes. In fact, I even call it “The Dream Time.” It’s all gone with the wind.

Peter Berlin: It was bliss. Back then, I liked live sex more than I liked porn. When I was in the bathhouses that showed porn in their lounge, it took me always two or three seconds to be immediately bored because what I saw is not what I wanted to see. I have a very limited erotic window. I’m not at all versatile. I could be the worst lay if I wasn’t careful. So I had to reject people who didn’t want what I want. When I was cruising the piers in New York, a guy followed me and started making small talk and ruined his chances. I said, “Talking is not the way it works for me. I have to start the minute we lay eyes on each other.” He said, “What do you mean?” He said, “Can we redo it? “I said, “Okay, I’ll stay here and you go to the other side of the street and start watching me.”

Jack Fritscher: The Peter Berlin Story: Scene 1. Take 2. You directed the scene and acted it out.

Peter Berlin: Then it worked for me. And he liked it. That’s what I would like a Peter Berlin movie to show. That kind of excitement without being X-rated. Especially now because of politics and censorship. There’s five million hot scenarios possible that aren’t X-rated. Brokeback Mountain was good, but not good enough.

Jack Fritscher: To timeline a film about you, when was Peter Berlin born?

Peter Berlin: The Peter Berlin character?

Jack Fritscher: Yes. [Laughs]

Peter Berlin: Peter Berlin was born in 1972 when I made my film Nights in Black Leather [released 1973]. I had to title it and put my name on it. I first put “Peter Burian” on it because there was a gay guy I thought beautiful who was named that in Berlin. Then suddenly this big envelope arrived from a lawyer in New York who accused me of stealing the name of Peter Burian who was a legitimate New York model. I was summoned to the office of that lawyer, and I said, “I’m sorry. I will change my name.” And then I thought of Berlin, and chose Peter Berlin.

Jack Fritscher: Warhol couldn’t have given you a better superstar name. It matches his superstar Brigid Berlin. You said Peter Berlin left the building about twenty years ago. So around the year 2000?

Peter Berlin: Yeah, it was a slow-motion exit, a shutting of a door. One night, I was cruising in Central Park. I was high and horny and feeling great. I looked up at the skyline, the buildings, Manhattan, and I said, “My God, I’m well over fifty. How long can this go on?” Peter Berlin was thirty when he was born. He was never young. He was never old. Peter Berlin is always thirty.

Jack Fritscher: You, Oscar Wilde, and Dorian Gray. The average age of a leading man in Hollywood has always been thirty-five.

Peter Berlin: People have always asked, “You do porno. What will you do when you are old?” I tell them I started when I was old, when I was thirty. Then I started just getting off by myself. I have a lot of unpublished videos of me getting off by myself. Do you get off by yourself?

Jack Fritscher: What? Quit the self-care act of gay magical thinking?

Peter Berlin: So then around 2000, I wasn’t going to the bars anymore. I was cruising Folsom Street and Ringold Alley for hours, and I’d be the last one on the street. I found myself rather alone. Standing in the dark under a streetlight. I thought “What is this?” Having sex was my career. One night, around three or four in the morning, I met Reggie who I’ve had sex with for twenty years. In my iPhone, I have lots of pictures of him and the dates we had sex.

Jack Fritscher: Finally, you’re taking notes.

Peter Berlin: The night we met, I looked at Reggie and thought, “Okay, Peter Berlin will meet Peter Berlin.” I was still sort of Peter Berlin, aging out of young Peter, and I thought maybe Reggie could also be Peter Berlin. He had a body like mine that I could dress up in Peter Berlin clothes. So I started dressing him as Peter Berlin and shooting pictures.

Jack Fritscher: You were already casting an actor in a Peter Berlin movie.

Peter Berlin: With a black man. When I met Reggie, I still had Bryce, this guy who was living with me. My lovers were Jochen [Labriola] until he died, then James [Stagner who was white] for twenty years until he died, and then Bryce [White who was black] until he died in 2005. Then Reggie moved in and I stopped going out. I only have sex with Reggie. I wash his clothes, shop for our groceries, and cook for him. I told Eric I live like an old housewife in bed with my cat drinking tea.

When James was extremely ill for a long time and I was caring for him in my apartment, it was a very touching scene. One day, he was so weak, he said, “Can you make the pudding?” I knew what he meant. So I said, “Vanilla or chocolate?” So I made the pudding and gave it to him, and he poured his whole bottle of morphine into the pudding and ate it. I told him to lie down. He said, “You’re always telling me what to do.” He fell asleep, slept for hours, and then he was gone. And then Bryce who was so sick died during heart surgery. When Reggie moved in, he said, “You’re not going to try to kill me too, are you?”

Jack Fritscher: Thank you for sharing that intimacy. What human scenes for your movie. But may I re-wind a bit? As a boy in Berlin, when did you first start dressing up?

Peter Berlin: I was in school where we all played sports. My grandmother had a sewing machine and I was tightening my shorts. I made them so tight that my sister said that people were talking behind my back. I did this very early on as a teenager. I found excitement in the sensation of tight clothing. Not only the look of it but the fit like a second skin. The feel of it. The constant vibration between skin and shorts.

Jack Fritscher: Peter Berlin wins the Battle of the Bulge. What a great mirror-fucking scene for your movie. A montage of how you evolved your look.

Peter Berlin: I always related to Marlene Dietrich and Marilyn Monroe. Miss Dietrich, you know, had this very tight see-through thing, and she wanted to have it sort of sparkling like it was electric. And Marilyn Monroe, when you think of her, you think not only of the blond hair and the face, but you think of her body that is so intriguing.

[In any feature film about Peter, this scene is an early necessity. In 1962, when Peter was twenty, he watched Marilyn Monroe on television singing “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” to Jack Kennedy. The moment is both scandalous and iconic. The world gasped and gaped. Her famous blond figure had been sewn into a skintight shimmering see-through gown designed by Bob Mackie who was famous for dressing Carol Burnett, Judy Garland, Liza Minnelli, Cher, and Bette Midler.]

Peter Berlin: When you think about Peter Berlin, the character, you think about him done up from head to toe.

Jack Fritscher: Yes, the whole body. Were you about ten years old when you started this?

Peter Berlin: Maybe not ten, because it happened around puberty. So maybe twelve or thirteen. A fetish even though I was not aware of fetish. I knew tight pants were a must for me to get out of the house as Peter Berlin. Right? I mean, when I was Peter Berlin, everything had to really be pulled together. So I leave the house and I become that character. Whenever I left the house, I was “Peter Berlin.” I played that character and I played him very well. I realized very quickly that I had to separate Armin from “Peter” because all that caused two kinds of reactions. I got a lot of negative reactions. I was aware that I was being looked at, but I didn’t want to be looked at by a family with children, right? I didn’t do my thing to be admired by the so-called public. That was not my thing.

I wasn’t, you know, courageous. I just was never in the closet. I wanted to get laid. I wanted to have someone who saw me start to follow me down the street which was the positive reaction that happened many times. In San Francisco, I usually wouldn’t go downtown to Union Square full of straight tourists. No. When you saw me on Polk, it was a gay street. At that time, I was living on Filbert Street and Polk Street. I would walk down to the Golden Gate YMCA past people who saw me every day. But I wouldn’t walk like that in some straight area. I always played on the gay field. At that time, I remember always seeing the hustlers standing on corners on Polk Street. I always was intrigued by hustlers. I always liked that scene. And, of course, I was basically seen as a hustler.

Jack Fritscher: Did you ever hustle? Mapplethorpe hustled a sandwich or two when he was a teen in Times Square in the 1960s.

Peter Berlin: No, I never, never hustled because I knew I didn’t have the credentials of a hustler. A hustler is selling his body and is doing what a client is telling him — and I don’t want anybody telling me what to do. So, I wouldn’t oblige, okay? People asked me, and I liked being mistaken for a hustler because that’s what I looked like.

Jack Fritscher: Perhaps you were like Coco Chanel who was so modern, someone said, that even though she wasn’t an out-and-out hooker or hustler, she’d settle for something in between being admired and being given gifts. Like you, she had two identities. One as a fashion designer. One as a singer in a cabaret popular with cavalry officers.

Peter Berlin: Oh! I don’t know her story. That is interesting.

Jack Fritscher: Two designers. She had her little black dress. You had your Saran Wrap jeans. I think of you like her as a unique fashion designer who fit the times. Your movies came out [1973 and 1974] just after the movie Cabaret [1972]. As if Peter Berlin stepped out of a Weimar cabaret. Berlin. Nazis. And all that jazz.

[By now there are so many gender-variant live stage versions of Cabaret, I can see the role of the Emcee played by Joel Grey being played in a homosurrealist fashion by an actor playing Peter Berlin wearing Peter Berlin drag. I’d pay to see “Peter Berlin” coming on stage shouting over the opening song’s powerful Kander vamp: “Meine Damen und Herren!” In truth, culturally and politically, creative director Armin’s Peter Berlin is at least subtextually a triumphant anti-fascist creation and divinely decadent symbol because he emerged from the war as an avant-garde next-gen incarnation of the degenerate gay art the Nazis tried to destroy. He was his own art object.

Standing in the shadow of his father killed by Nazi ideology, he grew up as part of his generation’s postwar reaction to Nazis. His proud DNA is in his thin silhouette. His fashion runway was the yellow-brick road that ran from Berlin to Paris to Rome to New York to San Francisco where he put down roots on Polk Street, still often called today by its original name, Polkstrasse, because of the German immigrants who settled there in the nineteenth century.

When Armin created Peter, he began performing beyond the narrow prescriptions of gender stereotypes. In the contours of global masculinity, Armin was all-male in body, spirit, and personality, and yet, he was perfectly androgynous. In the form and fashion of homomasculinity, Peter was both metaphor and contradiction. On the Rainbow Spectrum, he wasn’t hyper-masculine; he was homomasculine. He was perfect adjunct for the Cockettes crowd with whom he collaborated. He was too soft for the leather crowd which was why Peter was never featured in Drummer magazine — and why he had at first to pay Tom of Finland to draw his portraits which are now classic “Tom.”

His independence in identity and style was his homosurreal erotic power. His trans-Atlantic presentation of the platonic ideal of a sensuous European masculinity reads like “androgyny” which some queer progressives like as gender fluidity and some gay male conservatives hate as effeminate and decadent.

Everyone had an opinion about Peter Berlin. No one ever forgot their first sighting of him. When the immigrant Peter walked American streets during the Vietnam War doing his own thing, he upended conventions. He pushed boundaries. He was a challenge to the sliding order of gay masculinity on the Kinsey Scale. His aloof attitude and his outré clothing — a hybrid original of leather stylings for men not to be confused with drag for queens — were punk years before punk rock. Mapplethorpe, attuned to the early 70s rise of punk through Patti Smith, first shot the punkness of Peter on Polaroid in 1974.

When Vivienne Westwood began designing punk fashions in the early 1970s, she who dressed the Sex Pistols in 1975 was influenced by gay leather and bondage culture and by Peter’s disobedient style in his new films that thrust him into the international spotlight. Think of Peter’s Technicolor designer selfie standing like a ballet dancer on a garbage can, punk, wearing see-through gray tights from calves to tits, punker, and a stylishly reconfigured set of red suspenders holding up the tights and harnessing his chest, shoulders, and biceps in hints of bondage while wearing a red pillbox hat over a blond wig, punkest.

In March 2015, Lauren Murrow in San Francisco Magazine included Peter as the lead image in her photo-feature article “San Francisco: The Pioneers (The Pin-Ups, Porn Stars, and Provocateurs of San Francisco’s Sexual Heyday).” The mature Peter in a photo by Cody Pickens appeared alongside the Cockettes (Fayette Hauser, Scrumbly Koldewyn, Sweet Pam, and Rumi Missabu), Linda Martinez, David Steinberg, Joani Blank, Annie Sprinkle, and Jack Fritscher. It was the first time Peter and I were linked in the straight press after exhibiting our photos together for the SF Camerawork Exhibit: “An Autobiography of the San Francisco Bay Area, Part 2: The Future Lasts Forever,” 2010.]

Peter Berlin: You have a good sort of overall view I don’t have because I’m too close to myself. I became known as a person you might run into in the middle of the night in a bar or the street or a train station. Sometimes I meet people who remember me from that time, and they say, “Oh my God, you were a vision!” It was a thrill to have that effect on people. I always intended to be obvious because I tried to be an example, a role model, a blueprint, a template for guys to imitate. I always thought, my God, the best thing that could happen is that somebody looks at me and tries to imitate me. I encountered two or three who tried, but the imitations were always not as good as I did it.

Jack Fritscher: Right. [Laughs]

Peter Berlin: Now, you know.

[Regarding “Peter Berlin impersonators,” Dom Johnson reported on Vaginal Davis’s blog: “November 27, 2009: I also met…writer Bruce Benderson [a marvelous friend, insightful scholar, and longtime champion of Peter Berlin]… What a riot he is! It was the most peculiar night, as he had a British Peter Berlin lookalike staying with him, who is living as ‘Berlin circa 1975,’ and doing a project where he gets photographed in Berlinish poses by superstar photographers. He even got the aging original Peter Berlin to photograph him as his youthful self, which is pretty perverse…. Slava [Mogutin] was photographing the new [not the original] PB (with a Dutch bowl haircut, in slutty white string pantyhose, cowboy boots, and a little silk neckerchief).”]

Jack Fritscher: I know you’re authentic.

Peter Berlin: I did the best with the body I was born with because my frame when I look at my body compared to a black guy — when I go to the internet, I say, “Oh my God, if I could have looked like that, sure and confident.” I never was sure of myself even as I gave an impression of sureness and confidence. I was actually much more frail and insecure.

Jack Fritscher: How tall is Peter Berlin, and how much did he weigh?

Peter Berlin: Peter is five-foot-ten. I’m sort of five-ten, right? I was always on the thin side, 150 pounds. So I went to the YMCA to work out. My workout ran twenty minutes, lifting weights, but I never took it serious. I never liked the idea of a workout. I never liked the word work. I went to the gym because I could cruise and have sex there. I went there for the experience.

Jack Fritscher: As we all did at YMCAs everywhere.

Peter Berlin: I never got into the pleasure of lifting weights and feeling good the way runners get a runner high. Did you ever have a runner’s high?

Jack Fritscher: Oh, yeah. I spent years on treadmills and working out at the Y and Gold’s and the Pump Room.

Peter Berlin: If I run, I get a pain in my left or right side. So, I never had that runner’s pleasure. I worked out not to get big but to get a little definition.

Jack Fritscher: But you did develop killer abs.

Peter Berlin: I never had killer abs. [Laughs] I never had killer anything.

Jack Fritscher: You have killer abs in Nights in Black Leather. Nobody slouches and presents his washboard torso for worship like Peter Berlin.

Peter Berlin: But when I compare myself with the best, with what I see in the black guys! My God, I never was really happy with myself. But I said, “Okay, it’s not good enough” because for all the work I put in, I didn’t have enough drive to put real work into anything. Not like Mapplethorpe. He had drive. He did a lot of real work. Besides his sexual life, he was a worker.

Jack Fritscher: You certainly are in shape in your films. In what I think of as your signature move on screen, you thrust out your pelvis and your very tight torso, and you twist it from the waist, and pivot your shoulders thirty to forty degrees away from the plane of your waist. It accents your sixpack abs. I’ve watched your films in theaters full of men. And that makes audiences swoon.