How to Quote from this Material

Copyright Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. & Mark Hemry - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

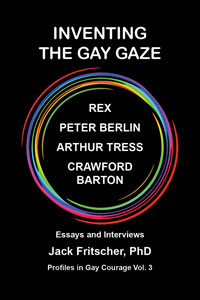

INVENTING THE GAY GAZE

Profiles in Gay Courage Vol 3

REX

REQUIEM

Corrupt Beyond Innocence His Life Before His Legend Became Myth

His Words and Thoughts

“Rex: Persona Non Grata” — Leslie-Lohman Gay Art Foundation, New York

“The world of Rex excludes you or draws you in at your own risk.” — Drummer magazine

“My drawings define who I became. There are no other ‘truths’ out there.” — Rex

Section 1: Rex Inventing Rex

Section 2: Swinging Sisties: Pioneer Gay Pop Artists

Section 3: Mattresses Stained with the Memory-Foam of Mansex

Section 4: Rex and Thom Gunn: Pinball Picture and Poem

Section 5: Rex, Religion, and Rimbaud

Section 6: Collaborating with Rex on Page and Screen

Section 7: The Rex Video: Rex Men Will Leave a Stain on Your Big Screen

Section 8: Touch-Activated Art Turns Nazi Taboo Into Totem

Section 9: Edward Hopper, Walt Whitman, and Gay Amnesia

Section 10: Rex at the Blue Muse Cafe

Section 11: Most Censored Gay American Artist

Section 12: The Eye of the Artist: Aging and Legacy

Section 13: A Room of One’s Own Petard

Section 14: Jealousy Is Self-Inflicted Masochism

Section 15: Exit Pursued by a Bear

Section 16: Rex Has Left the Building

1

REX INVENTING REX

Art is a harsh mistress. Art asks everything of the artist. Art keeps the artist alive until all that is left of the artist is the art.

Rexwerk, the summary name of Rex’s beautiful book of forbidden sex, smacks of Germanic discipline, of American homomasculinity, and of the authentic homosurreal art that imitates life the way, once upon a time, it was lived after midnight by men hunting other homomasculine men. Beginning in the 1960s, Rex helped create our gay culture that thrives on homoerotica because life enhanced by the renewable energy of Eros is the best panacea for gay men wounded by homophobia. He was a product of his own will. His work was his life.

This isn’t a history of Rex (1944-2024). It’s a memoir. An archival memoir. A personal eulogy in which renegade Rex speaks for himself revealing a new autobiographical visibility to a midcentury founder of the gay gaze. With the passing of this self-generating genius, the curtain can go up on the dramatic adventure of his high-brow and low-down life.

How strange. How sad to be 85 and waking Rex, 80, the last of the red-hot pioneers. He leaves this editor of Drummer magazine the last man standing in the “Tontine of Leather” in what the profound Sam Steward, friend of Gertrude and Alice, dubbed the “Drummer Salon.” Counting Rex, our vanishing circle disrupted art history, defied gay censorship, and entertained millions.

Our fraternity included a who’s who of Stonewall-era inventors of the gay gaze: artist Tom of Finland, emphysema, 71; photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, AIDS, 42; poet Thom Gunn, heart attack from acute polysubstance abuse, 74; author Sam Steward, pulmonary disease and barbiturate addiction, 84; filmmaker Fred Halsted, suicide after death of lover, 47; Oscar Streaker Robert Opel, murder, 39; artist A. Jay Shapiro, AIDS, 56; photographer Lou Thomas, AIDS, 56; artist Bill Ward, AIDS, 69; filmmaker Wakefield Poole, 85; artist Olaf Odegaard, 59; author Larry Townsend, non-AIDS pneumonia, 77; videographer David Hurles, complications from drug-induced stroke, 78; and a few others like artist Dom “Etienne” Orejudos, AIDS, 58.

As editor-in-chief of Drummer from 1977 to 1980, I was privileged by the centrality of Drummer to review and publish and socialize with these trailblazers. How exciting it was in that first decade after Stonewall when these men arrived at my desk and unzipped their brilliant portfolios that, in fact, helped create Drummer and the very leather culture they celebrated. See a “Tom.” Dress like Tom. See a “Rex.” Fuck like Rex.

In his origin story, Rex legally renamed himself “Rex West” invoking Marlboro cowboys when “Rex King” might have been more apt because “Rex” in Latin means “King” and he, never a queen, ruled the wild kingdom of Rex World. It may as well have been called Rex Neverland because Rex, whose self-defining late-in-life portfolio was his Peter Pan series, was a Lost Boy. He claimed he ran away from home to the streets as soon as he could, first at age eight, and finally at sixteen. He carried the gay gene for nostalgie de la boue: the erotic attraction to blue-collar men, low-life culture, skid-row adventures, and ritual degradation — redeemed by the magical thinking of orgasm as male worship. He was a socially distant mystery wrapped in a leather jacket.

What I write about him is memory struck from our mutual lives after we met in 1978. He whose birth name has yet to be revealed — because “Rex West” is on his passport which also claims he was born in Connecticut — was not one of those Beau Brummell dandies who polish their boots with champagne. Rex pissed beer on his kinky boots. There’s a maxim in the closing line in John Ford’s cowboy film about outlaws, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” Rex worked hard at the mystique of his legend. But history seeks facts.

When word circulated that after he finally rejected the United States, he had suffered and died alone in the last of his many self-imposed exiles far away in poverty and obscurity in Amsterdam around April 1, 2024. I suspected, knowing him, always a tempestuous trickster, that news of his death was perhaps an elaborate April Fool’s joke, like Tom Sawyer faking his own drowning to see what the world had to say about him.

At the same time the San Francisco Bay Area Reporter published a brief obituary on Rex on April 10, the New York Review of Books published its May 9 issue with a cover drawing by Tom of Finland to illustrate its long cover essay, “Tom’s Men.” What Jarrett Earnest wrote about Tom, who inspired Rex, made the same point I’ve made for years in Drummer about Robert Mapplethorpe’s revolutionary contribution to art — which applies equally to Robert, Rex, and Tom.

“Tom of Finland’s [Robert’s, Rex’s] work has transformed from midcentury gay pornography to twenty-first-century art, but its troubling dimensions, as well as the ways it has creatively shaped the desires of a diverse range of queer people, cannot be ignored.”

During one of our long conversations when Rex asked me to wait until he died to write about him with permission to quote him, it was as if he wanted the surety of at least one designated mourner who had observed, interviewed, and published him from the start of his long career.

In the Dutch morgue, there were no collectors of Rexwerk. And as far as is yet known, there were no personal mourners. But for those dying with no kin in Amsterdam, the Lonely Funeral Project provides a volunteer poet to read a custom poem based on what the departed revealed of his life. What could a poet say about an artist who kept his life secret? About an autistic man who committed social suicide cutting off people, gay culture, and an American nation he felt had betrayed him?

Our lives and careers ran parallel. I am a participatory New Journalist who liked him and never saw a Rex drawing that was not perfection. To promote the struggling artist, I wrote about him in Drummer and other magazines from the 1970s through the fin de siècle and was a producer of his Berlin exhibit, Rex Verboten at the Gallerie/The Ballery, during Folsom Europe Fair, September 2016.

For years, we collaborated, and talked on and off the record, depending on his mood swings. He always addressed me like I was an audience. I listened. He told me, “My work is very dependent on my moods.” He was a genius on paper where as a pointillist artist with both a Rapidograph Pen and a 3.5mm Rotring Ink Pen — inking like a tattoo artist dotting human skin — he controlled the million ink dots that composed each drawing. He was not happy that he could not control, could not dot the i’s and cross the t’s, of the gay press. He always knew what he wanted to do and how he wanted to position himself for public consumption.

When shooting the Rex Video Gallery: Corrupt Beyond Innocence for him in 1989, I suggested we needed a bang-up final shot. He said, “Go for the Dot.” He was not being reductive. He was being essential. He showed me how he had used a photocopier to keep enlarging one small dot from one of his million-dot drawings until that one dot grew to fill the entire frame.

In fact, the ultimate Rex drawing is that Dot which sums him up.

To honor his art direction, I used my macro close-up lens to enlarge one dot of one picture, drilling down more each take, the dot becoming larger, shedding literal meaning for abstraction, until the entire screen was filled with one last shot of one huge perfect Rex Dot. Now I mourn his life has come to an end. Dot. Dot. Dot. Full stop.

In May 1996, Rex, was anxiously coping with his issues and intense mood changes around abandonment, trust, betrayal, control, and social withdrawal.

Rex: I know I’ve been terse with you about writing about me in gay magazines. I have no reason to suspect you of anything, but crazy things happen like when my fans don’t destroy my letters to them. I destroy all my letters. When I let you publish my interview in your Mapplethorpe book [1994], I know it was absolutely quoted perfectly. It sounded like me as I was reading it. All the pauses, the commas, it was exactly the way I talk. It all came back to me. If you’re talking to the BBC, then you can talk freely about me. Excellent stuff. That’s a different context than writing something for a gay magazine.

If Alistair Cooke [BBC host of Masterpiece Theater] came over today, I’d sit right down and babble my head off…. If my life belongs anywhere, it belongs in an historical book, not in some porn smut gay rag. To sell gay magazines the editors want upbeat sexy articles. How many dogs did I suck and at what parties did I do it? And I don’t live that kind of life. I want to be revealed in my best light. I’ve gotten neurotic about this. That’s the way I am.

I don’t really mind when JD writes about me in his Trash magazine (hundreds of issues 1975-2020) because no one really reads it. [“JD” was Rex’s longtime friend, the vitriolic and aggressively reactionary conservative John Dagion (1935-2020) who retired from New Jersey to cruise young Mexican laborers at reststops in Republican Florida near the same time Rex fled to Amsterdam.] JD’s written more about what I’ve done and where I’ve been in life than anyone, and nobody actually sees it. He knows everything. I really think the man is a saint in a way. His porn is the best and I don’t think he is appreciated that much and I know he is sensitive to that so I try to support him. When you’re 65 like he is, you’re shaking anyway by just growing old. That’s an age when it’s hard to make new friends. Especially if you’re in the sex business. He’s basically retired. When I see him, I realize he’s an old man. When you’re growing old, you’ve got to take chances. We’re all isolated. As I was saying to JD, you know, the world is coming to an end.

Someday historians will need to go through his zine. I told [our mutual friends] Trent [Dunphy] and Bob [Mainardi] that it’s not that I mind you writing about me, but not while I’m alive. If you’re going to write about what I’ve told you, put it in a book of interviews where it belongs. From my point of view, you’ve always respected me and you should show respect for me on this. Tell people that’s just the way he is. Agreeable till he’s not. Tell them, “When he’s dead, we can print it. While he’s alive, it isn’t worth alienating him.”

Jack Fritscher: So I’ve got to outlive Rex? That’s a terrible bind we’re both in. This is like after I interviewed Sam Steward in 1972, he told me I couldn’t publish the interview until he was dead because he had to live off his stories [about Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, and Doctor Kinsey].

Rex: I don’t wish you dead. Of course, I’m going to outlive you. I’ll make sure of that.

Jack Fritscher: You’re going to outlive me?

Rex: Absolutely.

Jack Fritscher: You’ll make sure of it? [Because he worked for the Mafia, I joked.] Have you taken a contract out on me?

Rex: No. No. No. We’ll go on forever.

As an eyewitness monitoring his career, I had a constant human regard for him that often went unrequited. He was a voyeur who hated to be observed.

In the world of gay origin stories, Rex would not be the first gay teen escaping the closet of a bourgeois family home and rewilding himself as an outrageous outlaw with a new street name. Kafka, who liked to lick the legs of blond boys, said, “I am my stories.” Rex, who liked to lick the legs of leathermen, said, “I am my drawings.”

The self-possessed artist owned himself. He once told me during the many years we chatted for hours on the phone — when I took shorthand or recorded him by agreement — that he, who in his bestiary of men often drew horny canine companions, decided to call himself “Rex” because it was the perfect name for a dog who is man’s best friend. When Rex was a bookish teenager suffering the existential pains of an abandoned pup, he dived into Nietzsche and may have read his line, “I have given a name to my pain and call it dog.”

He repeatedly insisted he had been abandoned at birth — although, in a Greek-Dickensian plot twist, Oedipus Rex later said, in the 1990s, he reconciled with his mother whom he supported in a retirement home where she died and left him a fortune he lost in the stock market. He always concealed the 1944 year of his February 5 birthday which I calculated as closely as possible from his emails. On September 9, 2021, he wrote he was 78. On December 17, 2023, he wrote, “I’ll be 80 in less than two months”

A born fabulist hellbent on controlling his narrative, he impeded his own entry into art history. Rumors he himself may have started had it he was the black sheep son of a United States senator. Or some industrial magnate. Or some Mafia boss. In his kitchen-sink drama, he claimed as a young boy he had to work alongside rough itinerant field hands on a tobacco farm in Connecticut. He said he was an orphan who became a double orphan when his adoptive stepparents died. He said he drifted to New York in the 1960s where he told me he was a kept boy in his twenties, had half a dozen lovers, and attended art school on the dime of a sugar daddy. His longtime friend Clyde Wildes has a photo of Rex standing like a fashion model outside the Ritz Hotel, Place Vendome, Paris, December 1965. Whether his tangled origin story was fact or fiction, you’d have to ask the man who shot Liberty Valance.

In 1975, he told the Village Voice, “I nearly died seven times. I’ve been chic and elegant. I’ve had a nervous breakdown. I’ve been in three institutions. I’ve ridden with motorcycle gangs…. I’m thirty years old.”

After Rex died, a man who said Rex was once his lover told me that Rex, who was tending bar anonymously, told him he had been hired in the late 1960s as a staff artist for a cigar-chewing Mafia publisher who gave him the code name “Rex.”

At the time of the 1969 riot at the Stonewall Inn owned and managed by the Mafia, Rex was twenty-five and living in Greenwich Village where gays interacted for mutual benefit with the Genovese crime family who owned most of the gay bars. Two years later, on March 29, 1971, Francis Ford Coppola began romancing pop culture into the sexy allure of the Mafia when he started shooting The Godfather on location in the streets of Lower Manhattan.

Rex recalling his first decade in Manhattan said, “I was in New York long before Stonewall. I think I went by, on the night it happened, to the bars on Christopher Street. It was just a little disturbance with people caught between the Mafia and the cops. It was the 60s, there was always a disturbance going on. At the time, no one paid much attention outside the Village. Then, my God, it mushroomed!

“During the next year,” he said, “the gay press made a ‘thing’ out of it. It became like the landing of the Mayflower. There were only about a hundred people onboard, but a million people claim they’re connected to Plymouth Rock like the six million who rioted at Stonewall.

“I had gone to the Stonewall once. It was a little dance bar and now a little coffee shop. I first read about it in the gay press that turned it into a political symbol. Basically the police arrested some people in a bar raid. It was no pivotal moment in history. Think of all us who were already out for years. We’d already pivoted with our work.”

Rex was not married to the mob, but he may have fallen for some of the hot guido gangsters he met when he worked for Star Distribution. Star, the Mafia’s main publisher and distributor of adult material, was paying Rex to draw covers and illustrations for its 1970s gay pulp-fiction series Rough Trade. During those years, 1976-1985, his home bar where he was often hired for specific tasks was the Mafia-owned Mineshaft. Rex who liked tough guys and their attitude might have picked up a Rexian sense of their Sicilian omertà, their code of silence, a gay omertà born out of the protection of the closet, in his refusal to talk about himself even under questioning.

Young Rex was too provocative, disruptive, and subversive for his own good. He had reason to protect himself. Like gayish playwright Alfred Jarry saying “shit” in Paris in 1896, and gay writer Lytton Strachey saying “semen” in Bloomsbury in 1908, Rex said “leather S&M” in New York in 1975. He was a modernist trying to make gay art new. When the Psychedelic 1960s exploded in a glitter bomb at the 1969 Stonewall riot, gay character changed. Rex helped embolden the new decade with his art. He became persona non grata for challenging the fixed horizon of short-sighted establishment homosexuals. Rex took them to the edge and pushed them over the edge.

Five years into his career, his shocking pictures debuted suddenly like thunder in the New York press on July 7, 1975, when journalist Richard Goldstein, interviewing Rex about his new gay gaze, attacked him with an exposé in the Village Voice and labeled him a “Naziphile” for drawing explicit scenes of leathersex and saying, “The greatest S&M trip in history was the Nazis.”

To understand Richard Goldstein’s hyperventilating investigation of Rex, consider the source. Goldstein, the Voice rock critic who in 1967 created a media scandal when he irked Paul McCartney by trashing Sgt. Pepper after listening to it on a broken stereo, was a closeted gay man struggling with his identity while married to a woman. He told The Advocate in 2015 that his life experience at that time was like, God help us, the Boys in the Band. With his gaze on that miserable horizon in 1975, it was four years before he came out in 1979.

Pirandello would have had a picnic with these two characters in search of authenticities in the mix of art and politics. In Rex’s first media interview, why did he consent to play defendant to prosecutor Goldstein whose militant scorn was wrong for all his otherwise right reasons of anti-defamation vigilance? Whether Rex who called himself an anarchist was a Naziphile or a Nazi or a right-wing fascist conservative or not, the postmortem answer lies not in Goldstein’s confusions, but in readers studying the trajectory of Rex’s life and art while using critical ability to consider that my allegatians about Goldstein are based on Rex’s allegations about Goldstein as well as on research and on internal evidence in the Voice article itself.

As an iconoclast making new icons, the truth is, Rex broke the norms of received gay male identity. Like Tom of Finland and Robert Mapplethorpe, Rex glorified the new male selfhood and gender identity of post-Stonewall leather homomasculinity by turning symbols — Nazi, Catholic, Queer, American, and otherwise — on their heads while launching raw and radical S&M content as a bonafide subject in art.

Goldstein, like Susan Sontag who called leather culture “camp,” was investigating 1970s “Fascinating Fascism” and “Nazi Chic.” If Rex and his kind were camp to Sontag, why not to Goldstein? In an age of Nazi hunters, war-baby Goldstein (born like Rex in 1944) was en garde in his article,“S&M: The Dark Side of Gay Liberation: Flirting with Terminal Sex.” Calling out Rex as “Exhibit A,” he stopped short of calling Rex a “Nazi,” but did he overreach Rex — and himself — when he took a broad swipe at leather culture itself for flirting with fantasy fetishes of Nazi drag, insignia, and roleplay?

There is an irony that Goldstein’s article calculating the “horrors” of S&M was so filled with delicious information warning “what not to do” and “where not to go” that perversatile leathermen exiting the closet in 1975 re-purposed his words as a Gay Guide to S&M Things to Do and Leather Places to Go.

As a gay boy re-purposing media in 1950, I didn’t know dirty magazines existed until a priest clutching the pearls of his rosary warned us altar boys to keep custody of our eyes and avert our gaze away from the sinful men’s adventure magazines in drugstores where I rushed to feast my queer eye on bare-chested buddies fighting vicious animals on the cover of Argosy.

Gay boys growing up in a straight world learn to squint the gay squint that turns straight stuff gay. That’s the first and basic gay gaze.

Rex and I each cocked an eye to build our own teen spank banks. We both learned to narrow our eyes to blur busty Nazi blondes like “Ilsa: She-Wolf of the SS” on the cover of Saga, so we could focus on the well-built American soldiers Ilsa was tying up nearly nude in soft-porn articles like “The Conquering Fräuleins.”

In our postwar childhoods, we war babies grew up with American media portraying Nazis as escapist entertainment everywhere in a pop culture created to relieve the stress of a nation of veterans and home-front citizens dealing with the PTSD caused by the war.

In reaction, the 1960s and 1970s became a nostalgic period of swinging sex, transgressive art, and pop-culture cosplay. Rex’s contemporaries like the Beatles put Hitler obscured on the cover of Sgt. Pepper; Kenneth Anger shot gay Nazi bikers orgying across the screen in Scorpio Rising; the Residents art-band titled its album Third Reich Rock ‘n’ Roll; glam-rock metal bands and punk rockers like the Sex Pistols wore styles akin to the Nazi-spiked fashions of Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McClaren; Warhol shot his business manager Fred Hughes and socialite model Maxime de la Falaise wearing Hitler mustaches; Jim French of New York’s iconic Colt Studio named his porn studio after a phallic gun and pseudonymed himself as a fine artist after the famous German gun: “Luger”; Mel Brooks went camping with Springtime for Hitler; and 1970s films like Cabaret, The Night Porter, Seven Beauties, and Pasolini’s Salo sold tickets because audiences never tire of Nazi gowns and uniforms.

The activist culture critic, playwright, and university professor Sarah Schulman, a creator of the ACT UP Oral History Project, once asked in general “why some people are micro-critiqued, and others say and do vile, regressive things that get overlooked.”

What made Rex different from those diverse artists? What made Rex an easy target? What made Rex a “Naziphile”? Was it his politically incorrect point of view? Was it because he declared the constitutional rights of masculine Eros, and the free choice of consensual male domination and power, in a prescriptive feminist age when vanilla gays had no clue that leathermen were fisting Foucault right and left?

Rex stood out for better or worse because Rex always stood out. His smoldering personality was that provocative. His work was that good. Even before the Voice article drove him into seclusion, he was as much a cult artist as Tom of Finland. His fans who never thought of him as a political artist never quit the pointillist seer whose visions of erotic anarchy documented the iconography of the apolitical leather identity they lived.

Rex’s cool gay gaze, like the Drummer gay eye, was rooted in that postwar context of those pulp-mag artists who, mining Nazis as sexy gold, created the seductive covers of “straight male adventure magazines.” He built his repertoire by queering their aesthetic, and redrawing their images, for the emerging new genre of “gay male adventure magazines” like Drummer and Honcho that flourished during the Golden Age of gay magazines from 1975 until their death by internet in 1999.

Although Goldstein actually wrote he was personally “nauseated” by Rex’s art, to his credit, he never accused Rex, whose ethnicity remains unknown, of the mortal sin of antisemitism.

As a gay humanist, I have to ask why, as part of the commercial gay-pride establishment in New York, did Goldstein try to sound an alarm on Rex and leather culture itself? Was Rex in leather drag typecast as a convenient polar opposite of leftist gays in Stonewall drag? Did Goldstein correctly sense that Rex was a nascent conservative leaning right as seems later in Rex’s own words in our interviews? Was there gay-on-gay animosity because of leathermen’s own brand of gay male masculinity, denounced as politically incorrect, with its erotic rituals and dedicated bars with virile dress codes that, like women’s safe spaces excluding men, excluded effeminacy with door signs like “Leathers Not Sweaters.”

One short year later, as Goldstein had cautioned, the Leather Apocalypse arrived on a cloud of poppers when the quintessential leather club, the Mineshaft, opened its world-famous door, bathtub, slings, and buckets of Crisco to thousands of international leathermen with Rex as its official artist till its closing eight years later.

“It’s almost,” Goldstein, a constant critic of male power, wrote, “as if gay culture has taken on the Yeatsian task of creating its own rough beast — the leather man.”

Did he really think that garden-variety homosexual hedonists playing at being sexual outlaws sporting hankies, nipple-clamps, designer vests, and Iron Crosses as junk jewelry in leather bars were neo-Nazi Hells Angels?

The spring-loaded wisecrack about the “anarchy of man-beasts” and the “end-time chaos” of leather revelations included visual exploitation. At least, the page design looked very like sexploitation. Did the publisher have a double motive? The anti-leather page layout took the opportunity to illustrate itself with two S&M drawings of Rex’s “rough beasts” because that kind of prurient “Exhibit B,” for readers squinting to find bits of porn to take in hand and re-purpose, would sell more copies on newsstands.

It’s to Rex’s credit that the penniless artist won many column inches of free publicity in the Voice when he stood up for himself with clever ripostes about the human worth of leather culture, about the evils of corporate culture, and about his theories around American religion, politics, and fascism that have since come true.

From my interaction with Rex, the Voice feature because it found valid reasons to question his art and politics wounded him deeply. Rex never suffered critics gladly. Feeling scapegoated, the autistic artist was all on his lonesome without much fraternal support when the Voice hit the streets three weeks after publication of the first issue of Drummer. That West Coast leather magazine, unknown to Goldstein, escaped the Voice inquisition even as it became a refuge for Rex, and the international magazine of record for twentieth-century leather culture.

In 2004, Goldstein alleged he was fired by the evolving Village Voice. He threatened a lawsuit, and went on writing books excoriating the formal gay right of which the independent Rex, who was no Leni Riefenstahl, was never a part.

Whether history finds Rex’s avant-garde work Naziana or not, the article deprived the struggling homomasculine gender artist of nuance and cast him as a villain in the cultural narrative of gaystream gatekeepers.

The PTSD he suffered was collateral damage not intended by Goldstein, but the high-profile trauma ignited his lifelong distrust of the gay press. He began guarding himself with fierce anxiety.

“The Press!”

That complaint was the first thing that came out of his mouth the first time we met. Was he spinning reverse psychology every time he proclaimed he did not want to be in gay magazines to cover for the fact that the national gay press loudly warned by the Village Voice was afraid of him and his shocking, and sometimes illegal, art in their pages?

To correct that, Drummer rode to his rescue and published his first magazine cover drawing on issue 10, November 1976. Years later when he was living bicoastally, he told me about his misbegotten return to New York in 1992 to open his own “appointment only” Secret Museum Gallery (1992-2001). It was a little too secret. What a shock when, seeking his canonical due, he began making the rounds of the new young millennial magazine editors who had taken over publishing lacking mentoring from the previous generation-gap of editors dead from AIDS. Anyone can open a gallery. They had no idea who he was and they didn’t care what embarrassing veterans of the gay liberation wars they left behind. They scratched their heads and touched their man buns because Rex was off their gaydar. The internet did not exist before 1993, and they could not be bothered to look at the extreme portfolio of some vaguely vagrant old guy they did not know was a transgressive beat-punk artist years before Patti Smith sang at Hilly Crystal’s CBGB in the East Village.

Jack: As an artist, how do you defend your problematical and often outlaw material? How do you face editors and critics?

Rex: I don’t have to face them because I never face anyone.

Jack: But your work does. It’s so much beyond the pale.

Rex: They will talk to the work and the work will talk to them and it will end there. I know a lot of people who are appalled by my work, but they never confront me or address me.

In 1976, Rex became the official artist of the legendary after-hours club, the Mineshaft (1976-1985), two years before his friend, the other keen eye, Robert Mapplethorpe, became its official photographer. Rex was two years older than Mapplethorpe who collected his drawings. I remember one day at lunch on Castro when Robert asked Rex: “How do you do it? How do you make your drawings so erotic?” Rex just smiled and said, “More pasta?” The blistering raw eroticism Robert saw in Rex, and hungered for, he never achieved.

Rex is to drawing what Mapplethorpe is to photography, but Rex is edgier with a mise-en-scène more daring than the cool formal world of Mapplethorpe who had to deal with temperamental living models while the unfettered Rex without borders pulled his conceptual models out of his chiaroscuro imagination — or from magazine photographs as did Mapplethorpe in his collages.

If Mapplethorpe flew first-class on private jets with his patrons, Rex rode slouched across the cheap seats at the back of a Greyhound bus jacking off the hard men of his dreams and collecting dots of cum. While Mapplethorpe created his pictures for the eyes of the professional art world of critics and collectors, Rex created his perfect moments for the eyes of ordinary people who relate personally to his images in which they find emotional satisfaction they may not be able to analyze. Mapplethorpe told clients, “If you don’t like this picture, maybe you’re not as avant-garde as you think.” Rex had the very same attitude.

Rex once told me: “I want to draw pictures nobody has seen before.”

Mapplethorpe once told me: “I want to be a story told in beds at night around the world.”

Profiling Rex in Drummer 12, January 1977, with three Rex drawings in the article, “Rex: Unusual Erotic Work from a Superb Leather Artist,” we rebutted the Village Voice. One image we published pictured a muscleman on the telephone, and the other a sailor riding exposed and hard on the subway slouched under a poster that Rex had Rexified of the Marlboro Man whom both Rex and Drummer kept in mind as a source image. The same issue illustrated reporter Gary Collins’ exposé of prison sex horrors in his lead feature, “Male Rape,” with Rex’s gang-bang drawing, “Male Rape.”

As keeper of the Drummer Archives, I’m quoting here that Rex article — that has no byline — to give Rex fans, readers, and researchers direct access now and in the future to this hard-to-find classic issue because this is the kind of reportage most likely written by Oscar Streaker Robert Opel who wrote a series about artists in Drummer issues 2, 4, 9, and 13, culminating in his interview with Tom of Finland in issue 22.

The evidence of Opel’s authorship lies in the timeline. Opel would have written this January article for publicity at the same time he was writing publicity for his April show at his Fey-Way Gallery where, before he was murdered there July 7, 1979, he mounted the first Rex Exhibit in San Francisco: Rex Originals, April 8-19, 1978.

Rex came to Drummer, hat in hand, in the 1970s, almost at the same moment as did Mapplethorpe with his hat because both New Yorkers needed monthly Drummer to build their brands with thousands of national and international readers. In 1989, Drummer continued its general support of sexy Rexy by specifically promoting him in its “Second Short Story Contest” seeking fiction based on a Rex drawing. Years later, in 2018, the New York Times published “A Trio of Short Fictions Inspired by Robert Mapplethorpe Photographs” written by Michael Cunningham, Elif Batuman, and Hilton Als.

Drummer was a first draft of leather art history with its star-making adoration of talents like Rex, its coverage of his drawing process and of his first live-work studio in New York at 178 Christopher Street conveniently next door to the marvelously sleazy Christopher Hotel at 180 Christopher where leathermen rented rooms by the hour, and Rex spent nights, months, and years of sex research on his knees studying tableaux of life models in knock-down-and-drag-out scenes he turned into art. During the Golden Age of Gay Magazines (1975-2000), gay artists from Rex to Mapplethorpe to Bill Ward, who was the artist most published in Drummer, to Tom of Finland needed and courted editors to build their careers in the national web of gay magazines that started up after Stonewall, crashed with AIDS, and died at the dawn of the internet.

Drummer reported:

“Uh, there really is a Rex, isn’t there?” The voice answering on the telephone is hesitant. It’s a fair question. Though the drawings that are signed “Rex” are earthy, highly real and personal, still there is something in that technique that doesn’t seem quite human. Something suggests the infinite detail of a photograph. But if you pick up a magnifying glass to check it out, well, it’s only lines and dots and black and white after all. A drawing doesn’t give itself up to you like a photograph. It eludes you.

There is a Rex, but Rex doesn’t give himself up to you either. Not many people meet Rex. An interview? It’s out of the question. Reserved, intense, wary of outsiders and newcomers, Rex is an enigma, as disciplined and demanding in himself as the taut technique of his drawings. He’s handsome: fine sharp features, dark hair, tight-muscled, the classic grin of a GI. Definitely handsome, and always soberly dressed in black, always wearing those thick-soled German army boots you sometimes see in Rex drawings.

Rex lives and works in the kind of fortress you get used to in New York. A cool dark space with a precision finish. Photographs are everywhere — men, machines, aircraft hangars, horses, and Tom of Finland drawings. “Everyone,” Rex says if you ask him, “owes Tom a lot. He took the rugged American man, made him larger than life, and gave him back to us.”

In a room like a bunker, drawings for the next Rex book are tacked to cork walls below a khaki parachute that spills out of an army helmet in the center of the ceiling. Some of the drawings are finished, just the way they’ll be published. Others are being worked on, a process that can take months. The outlines are already there, the male flesh still blank, perhaps just a leather sleeve Rex has totally completed, highlights glistening, the teeth of a zipper. Already they are beautiful and hot just like that, unfinished. (“A drawing is complete at several stages,” Rex said once. “Something in each stage has to be sacrificed to the final drawing.”)

What makes the finished drawings so hot? For one thing, these are not pretty fellows all draped in fetish symbols. The boots and leathers, the uniforms, the clamps and chains express a horny urgency. The men who grapple with each other with such a fierce passion are not always even handsome. Some of the best men in the world of Rex are brutal.

Rex never sets up a narrative series. All the story is there in one flash, telescoped into a single moment and isolated on the page. These are drawings you look at one at a time. In each one, Rex distills the action we have all seen, done, or imagined, but which we get to bring off only rarely and never so well.

The settings are immediate. The action can’t wait for a safe place or better time; it explodes on the spot, in the johns, on a subway car, in lockers or a room at the Y. But there’s a cryptic quality in the atmosphere, a sense that even the litter on a seedy hotel room floor carries a special message. Though you recognize some familiar images, Rex gives them a private twist. Take the classic leatherman on the cover of Männespielen: A Portfolio by Rex. Rex captures the dull shine of his jacket and the topman’s traditional leather cap, but you can’t read the expression in his eyes; they are strangely remote. And he licks his lip in a disconcerting gesture. Why? In anticipation? A cool appraisal? There is something elusive and seductive in these details, too.

And the titles! Last year, hardly anyone knew the meaning of Männespielen (let alone how to say it). Rex explains it as German slang meaning men’s games, a kind of rough locker-room horseplay. The games these men are into make heavy horseplay: games of power, games of submission, played out in an intense hush.

His new book is called Icons. Images of worship. And new games that express a kind of rugged communion. Rex is finer than ever. He draws his icons from his own world. The world of Rex excludes you or draws you in at your own risk.

Those who never got a friendly flash from a sailor in the subway might see Rex drawings as a pure exercise in fantasy. But the Drummer man who moves in this world himself? He knows.

After Opel’s January 1977 Drummer article, I first wrote about Rex in my feature about the Mineshaft in Drummer 19, December 1977.

The Mineshaft Is a Fantasy by Rex. The essence of the Mineshaft is found in page after page of Rex’s drawings in Männespielen and Icons. If you get off on Rex, you’ll like the Mineshaft and you’ll understand why the Mineshaft chose him to design its 1978 poster and T-shirt. Rex epitomizes in his work the concept of the Mineshaft Man.

Within days of publication, Rex sent me five drawings and a letter expressing his gratitude for coverage in Drummer. I responded on February 16, 1978.

Dear Rex, Thanks for your letter full of kind words on my writing and for the even more generous gift of your latest work…I’d be delighted to write an article featuring your professional “comeback” [after the Village Voice fiasco] with your approval of the copy as well as make a point of your new mail-order availability. I will, as you desire, focus on your work rather than on you personally. The discipline in your work has long impressed me. Yours, Jack Fritscher, Editor-in-Chief

He responded in a letter dated February 21, 1978, airing his smoldering resentment of the New York establishment misunderstanding his art.

Dear Jack: Thank you for your letter of the 16th. I am most grateful for any coverage I might get from your publication, especially at this transitional stage of my career. I’m enclosing the drawings you requested…. I would very much like to see your viewpoint about my work, much as you interpreted the Mineshaft poster. You’ll be more objective about the work and I would definitely want some critical points mentioned…. I’ve a great many critics…. A paragraph exploring my [New York] detractors would prove most interesting…. Many thanks for your help, Rex.

Rex was a visionary artist of gender, of homomasculinity, for men who prefer men masculine. That made him a perfect match for Drummer which published his work and his equally hot commercial advertisements for popper companies, leather bars, and telephone sex lines. Durk Dehner, co-founder of the Tom of Finland Foundation in 1984, who labeled both Tom’s work and Rex’s work homomasculine, wrote: “Drummer, ground-breaking for its time, set precedence for all male representation to come.”

Rex played an important part in creating the virilizing homomasculine standard of positive male gender presentation that became Drummer policy. Rex’s gay eye helped usher in the New Wave of gay masculinity that came out of the closet in the 1970s in life and on page and screen. While he drew the faces of homomasculinity, critics often mistake his homomasculine work as toxic hyper-masculinity.

But gay homomasculinity is not straight hyper-masculinity which is a negative term embracing midcentury military toughness, misogyny, and male supremacy wrongly applied to the gender-positive work of Rex and Tom of Finland. Critics liking labels might do well to consider that the work of Rex and Tom is not hyper-masculine. Durk Dehner emphatically said, “Tom’s work is homomasculine.”

Hyper-masculinity is an exaggeration of aggressive XYY male behavior and bodies that like Neanderthals don’t fit in our majority XY culture. Studies report a large percentage of the American male prison population is locked up for being XYY.

Ringmaster Rex was fascinated by the menagerie of gay desire in the zoo of gay bars where thousands of men presented themselves magically zipped up, and shape-shifting identity like ritual animals — anthromorphic bulls, bears, pigs, ponies, dawgs, and pups — vested head to foot in the virilizing fetish of blue-collar clothes cut from full-grain cow hide.

He established his zoological art as edgy and bad-ass when he broke the taboo against bestiality which he made literal by adding man’s best friend to many of his pictures. He assaulted the gay gaze, and panicked the gay press, by turning taboos into totems representing emerging new queer masculine animality. He drew Montague men for hero worship by Capulet men who, like him, were homomasculinists born with a fatal attraction to bad boys and the dangerous hyper-masculinity of onward-marching soldiers of religion, nationalism, and capitalism.

Rex drew his men to look “straight” because he liked men that way and because of the gay fetish “in search of” straight men. His men read as masculine-identified men “in search of” one another, like a pair of straight Marines on leave drunk-fucking each other in a cheap motel with not a gay culture thought in their buzz-cut heads. Freud warned in Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality that “concepts of masculinity, like those of femininity, whose meanings seem so unambiguous to ordinary people, are among the most confused that occur in science.” So, why not query homomasculinity?

Rex’s sophisticated drawing for the landmark twentieth anniversary issue of Drummer 100 (November 1986) is an icon of his platonic ideal of a leatherman. His hard-boiled cover image of a hairy-chested muscle biker with a cigarette dangling from his insouciant lip evokes a cynical underworld anti-hero in a lobby poster for a Hollywood film noir unreeling in a fleapit theater that’s seen better days.

Rex was a fine artist with a keen eye who prowled “half-deserted streets” and dared “visions and revisions.” He was a skid-row existentialist of “J. Alfred Prufrock” proportions. His rented rooms where men come and go fucking with Michael and Angelo were inspired by the archetypal rooms he cruised in the molly-house of the Christopher Street Hotel. As a “landlord” managing the rooms in his voyeuristic drawings, his proprietary point of view was the gay gaze of a slum lord spying on his tenants through keyholes.

In his 12-10-2015 picture “The Nightwatch,” he “drew from life” documenting the scene in the sex-cellar Darkroom of Amsterdam’s Cuckoo’s Nest bar. As an ancient eye revealing his lifelong voyeurism in the 9”x18” drawing, he included a tiny selfie of his own face hiding in a corner spying on the leathermen carousing in the basement orgy room where he spent many a night smoking dope and sniffing poppers.

His real-estate locations in his erotic imaginarium read like a road guide to YMCAs, saloons, toilets, flophouses, carnivals, prisons, shipyards, and truck stops cruised by itinerant construction workers, greasy gas jockeys, muscle bikers, tattooed fighters, succulent young bums, pissing ex-cons, armpit suckers, studs seeking head, and the rogue cops who roust them.

Rex’s men are unshaved lone wolves in jockstraps, leather, boots, and torn tank tops, who ring their tits and pierce their dicks tied off with leather thongs, who pay-per-hour in sleaze-bag hot-bed hotels where sailors, Semper-Fi Marines, cops, and drifters flop back on cum-stained mattresses — the smoke of their cigarettes drafting out the crack of their door down the hall to the common washroom where other grifters running power games of humiliation and domination stand around the funky urinal dripping beer piss, and the graffiti-covered stalls are drilled with gloryholes glazed like donuts with cum.

Rex told me, “Everybody thinks I can draw everything whereas I am extremely limited. I give that impression because I am so shrewd about limiting my repertoire. What I can’t do, I don’t do. So when you think I can draw everything, I don’t show you the things I can’t draw. In my pictures you never go outside because I can’t draw nature. That’s why I have to stage my sex scenes indoors at night, because I can’t draw nature.”

Rex’s work invokes the human solitude of straight painter Edward Hopper who featured lone women waiting in the noir spaces and all-nite diners in his suggestive night paintings, “Office at Night,” and “Night Windows.” Hopper’s superb “Nighthawks” became such a pop-culture icon it was parodied by Austrian artist Gottlieb Helnwein who, recreating Hopper’s exact interior, inserted four movie stars to replace the original figures in Hopper’s midnight diner: Elvis is the soda jerk serving James Dean sitting solo at the counter to the left of Marilyn Monroe laughing with Humphrey Bogart. How interesting if Rex had ever tried to Rexify “Nighthawks” with a quartet of Rex men.

His pictures feature men dealing erotically with masculine isolation and existential loneliness, killing time with sex during restless nights in single-room-occupancy hotels, dive bars, and gas stations warming hot dogs on roller grills. He limns a short-order cook out of “Nighthawks” in his chrome-plated diner drawing dated 1-9-82. Created from his study of his life lived on the skids, his art, exquisitely corrupt beyond innocence, is authentic.

He once informed me: “I’ve had enough sex to know what happens in the world. I don’t think I’ve ever drawn something that I haven’t done or known someone who’s done it.”

On July 2, 1979, when William Friedkin, the Oscar-winning director of The Boys in the Band, The French Connection, and The Exorcist, began filming Cruising on location in the streets of the Village, Rex was traumatized once again by the Village Voice whose war on Cruising was yet another of its assaults on leather culture. In the July 16 issue, staff reporter Arthur Bell (1939-1984) attacked the film, leather decorum, and Rex’s Mineshaft when he incited violence by calling up mobs to “give Friedkin and his production crew a terrible time if you spot them in your neighborhood.” Bell and his henchman, the troubled Vito Russo, the author of The Celluloid Closet, impugning the shooting script, tried to cancel the creative process of director, cast, and crew whose film, as art-in-progress, they were disrupting with no idea of the holistic final cut. So much for critical thinking in the gay civil war.

Even John Rechy, no lover of leather, spoke out against Bell’s “prior censorship.” Distressed by Bell’s propaganda, Rex, forever the consummate New York artist, realized he had to exile himself from New York. So in 1980, he followed gay migration westward moving like Harvey Milk, who had his own appointment in Samarra, from the gated cliques of Manhattan to the open city of San Francisco. Like his peer, fine artist and photographer Jim French aka Rip Colt of Colt Studio, he left behind his dark New York studio to open up his second act to new West Coast vibes.

On March 1, 1981, Rex, the recluse, hosted the opening exhibit of his San Francisco studio and gallery and home South of Market Street in a three-story Victorian, fifty feet off Folsom Street, at the deep dead-end of the Hallam Street cul de sac. Like his New York home next door to the Christopher Hotel, it was conveniently located sixty feet across the narrow lane from the entrance to the orgiastic Barracks bathhouse that opened in an abandoned blue-collar flophouse hotel, May 15, 1972, where the action was also what Rex witnessed at the St. Mark’s bath at 6 St. Mark’s Place in the East Village. The crisp designer interior he created for his studio in the light-industrial slums of SOMA was very New York: black walls, gray carpet, and track-lighting spotting his framed drawings and his work in progress.

Three months later, on July 3, the New York Times announced the news: “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals: Outbreak Occurs Among Men in New York and California — 8 Died Inside 2 Years.”

One week later, on July 10, outside Rex’s studio windows, the mythic Barracks, vacated for renovation, exploded in an arson fire that traumatized him on top of the traumas he suffered from the Village Voice. The worst fire in San Francisco since the 1906 earthquake burned his new Rexwerk atelier to the ground and made him so famously homeless that the Mineshaft back in New York hosted a fundraiser so he could keep on working in San Francisco. Mineshaft manager Wally Wallace told me in our 1990 video interview, “Rex is our Michelangelo. So is Tom. So is A. Jay.”

In the Mineshaft Newsletter, Wally Wallace wrote:

CASINO NIGHT TO HELP A BUDDY OUT. (Rex Benefit) TUES. OCT 20 [1981] 9-12 PM. In July the largest fire since its earthquake swept the Folsom Street area in San Francisco leaving 120 totally homeless. One of the victims was Rex, the artist of the Mineshaft logo, who lost all his earthly belongings in one night. The Mineshaft gave a benefit for him in San Francisco and now we are having one in New York from 9 until Midnight on Tuesday, October 20th. It’s a Casino Night with lots of prizes for the winners…with some recent Rex work on display…. Please note that another Casino Night will be held in early November for the Gay Men’s Chorus and their Bux for Tux Fund.

With the Mineshaft proceeds, Rex rented a squat in a warren of rooms at 199 Valencia above the popular gay leather biker bar, the Rainbow Cattle Company, which was later renamed Zeitgeist. He told his gallerist friend Bernd Althans that because of his post-traumatic stress about the fire, he did not leave his room and did not draw for a year. When finally he quietly picked up his pen, he drew some of his best work. Overcoming his depression, he rose like a phoenix from the ashes of the fire, and created a poster offering his new drawing “Phoenix” as an original signed Rex picture to support AIDS research in New York: “Win the Rex drawing ‘Phoenix.’ Support Karposi’s Sarcoma Research at the NYU Medical Center. [Raffle] Drawing at the Spike, 120 Eleventh Avenue, September 22, 1982.” “Phoenix,” signifying his recovery and resurrection, then became the cover of Rexwerk, published by Les Pirates Associes Editeur, Paris, 1986.

One of the few pre-fire works to survive was his drawing “Leather Bar” — picturing seven leathermen standing side by side — which he had drawn and then leased as a poster-advertisement for French director Jacques Scandaleri’s 1978 erotic film, New York City Inferno, the first film shot inside the Mineshaft. The movie featured leather poet-artist Camille O’Grady, fresh from CBGB, singing her piss song “Toilet Kiss” with her band Leather Secrets. Scandaleri returned the original drawing to Rex in New York in the 1990s. In 2013, three years before Rex would be inducted into the Tom of Finland Foundation Hall of Fame, he gifted “Leather Bar,” his earliest surviving original, to the permanent collection of Tom’s Foundation.

Later during Covid, Rex said his life always lurched from disaster to disaster. Nevertheless, it seemed no headlines, plagues, fires, and politically correct critics could ever dent his true grit.

Rex told the Tom of Finland Foundation in 2017:

People say I’m stubborn just for the sake of being difficult — just to have my way. But I’m someone who has had to fight for decades against society, the law, church and state — even the art world itself — in order to get my art before the public uncensored. There is simply no “polite” way to battle against these great odds that I have had to battle against for the past five decades. Saying “please” does not work when taking on these powerful, entrenched institutions. So I fear fighting the status-quo in the long run has made me rather abrasive and abrupt at times when trying to get my art before a society that essentially won’t allow it to be seen. Or rather, allow it to be seen on “my terms.” But my bark is worse than my bite.

Durk Dehner wrote in the Tom of Finland Foundation Newsletter:

Rex is well versed in the knowledge of our base cravings and desires and that same force has driven him to meticulously lay down scenarios that others dare not manifest. He has been adept at creating imagery that pays homage to that nature that gives us the strongest of erections with the most powerful of orgasms. [Italics added] Both Rex and Tom of Finland did not want to compromise their freedom of expression in exchange for getting the approval of the greater society in which we live.

From the start of his career, Rex, like Mapplethorpe with his XYZ Portfolio, turned to self-publishing keeping in print his run of softbound 36-page unbound portfolio “books” that began in 1975 with Männespielen, and continued with Icons, graduating to his first hardcover book, Rexwerk (1986).

But the politics and ignorance during the long slow-motion fall of the American Empire that — years before 9/11 — began with the assassination of JFK in 1963 and picked up speed with Reagan denying AIDS in the 1980s, turned America’s greatest living gay erotic artist into the expatriate who in 2011 fled America for Amsterdam where erotic joy and backrooms reminded him of the best of the 1970s in New York and San Francisco.

2

SWINGING SIXTIES: PIONEER GAY POP ARTISTS

The artists who were Rex’s contemporaries were an international underground of homomasculine art appreciated for its aesthetics inside the pop art of the Warhol 1960s. When the Tom of Finland Foundation named Rex to its Hall of Fame in 2016, Rex wrote in the TOFF Newsletter:

Mine was the first generation that came out of the closet to the art world a decade before Stonewall. We paid a heavy price in those early days for drawing dirty pictures as they were then called, sacrificing in many cases, our lives, jobs, family ties, and homes for daring to depict “The Love That Dare Not Speak Its Name.” Our art was burned and destroyed in raids by police and postal authorities. The work was condemned and spit upon by church and state, and especially by the legitimate art world for whom we were rude intruders storming the gates of their conservative ivory towers. What we dared to depict of the naked male form were criminal acts back then and those of us who portrayed them, criminals.

Tom of Finland, who as a teen in occupied Finland had sex with Nazi soldiers whose politics he hated, but whose uniforms he loved, drew clean-cut blond Aryans while Rex’s barbarian Aryans have their own Nazi genes courtesy of Rex’s own Nazi fetish. If ritual S&M fantasies became real, they’d be homophobic nightmares — and that’s the counterphobic thrill of the magical thinking of masturbation and sex play as sexual healing that Richard Goldstein never considered.

The New York S&M artist Mike Miksche aka Steve Masters (1925-1965), who in the 1960s excited the young Rex, was the six-foot-five bomber pilot and real-life Marlboro Man model and sadistic suicide who beat up Sam Steward (1909-1993) consensually for the camera of sex-researcher Alfred Kinsey. In his crisp tattoo-inflected Vitruvian-man style, he drew the strength of post-war gay men, posturing tattooed cousins of Rex men, made defiant by their military service, and made proud by winning the war.

Masters and fellow New York artist Jim French (1932-2017) who was the founding photographer of Colt Studio in 1967 with my longtime friend Lou Thomas (1933-1990), founder of Target Studio, who shot a dozen Drummer covers, were both Madison Avenue advertising men with formal training who drew and photographed butch guys in the New York S&M leather scene. French aka the fine artist “Luger” aka “Rip Colt” photographed and then sketched the same kind of alpha men Rex drew. Rex, however, flipped French’s aesthetic of Colt men who were aloof, unavailable, clean-cut sex gods to be worshiped. His Rex men were alternative sex gods, muscular, aggressive, sweaty brutes to be served.

Chicago artist Domingo Francisco Juan Esteban Orejudos aka Dom aka Etienne (1933-1991) was co-founder with photographer Chuck Renslow (1929-2017) of Kris Studio, the Gold Coast bar, and the International Mr. Leather contest. Like Rex, Dom also created kinky bar ads, posters, and illustrations of leathermen evoking folk-art circus banners not unlike the mustached “Strong Man” and tattooed “Sword Swallower” in fantasy paintings flapping on canvas panels hanging outside peep shows and freak shows lining carnival midways. His images, like Rex’s intense carnival and Sex-Freak Circus images, were primal and had romantic appeal because they tripped leathermen smoking pot and drinking beer in his Gold Coast bar back to a time when things seemed simpler for a brokeback man on a motorcycle. Dom introduced the concept of “gay bars as art galleries” when he premiered his murals inside the Gold Coast he and Chuck founded in 1958, four or five years after the world’s most likely first leather bar, Cinema, as reported in Larry Townsend’s 1972 Leatherman’s Handbook, opened in 1953/4 on Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles.

Al Shapiro aka A. Jay (1932-1987), the art director of Clark Polak’s Drum magazine (1964-1967) which Rex read, was also the founding New York art director of Queens Quarterly (1969). For the June 1974 cover of QQ — which likely helped trigger the Village Voice attack on Rex in 1975 — Al published a rare color drawing by Rex just before Al quit QQ to move to San Francisco where I met him and his new lover Dick Kriegmont at the Barracks baths in late summer 1974. Three years later in a package deal, Al and I joined Drummer together as art director and editor-in-chief: March 17, 1977 to January 1, 1980.

While Rex was deadly serious about male representation, the good-natured Al satirized homomasculine sex, leather fetishes, and camp in his monthly cartoon strip, The Adventures of Harry Chess — which, beginning in Polak’s Drum (10,000 circulation) before moving to Drummer (42,000 circulation), was the world’s first ongoing gay comic strip. Almost in tandem, Rex’s first Drummer cover was issue 10, November 1976. Al’s first cover was issue 15, May 1977. Rex’s gay gaze presented one kind of “leatherman look” on the cover and Al’s quite another. In 1980, Al told me in his Drummer interview: “I marvel at Rex’s technical aplomb and his sleazy male content.”

Don Merrick (1929-1990) aka Domino was a New Jersey construction worker, lumberjack, and cab driver who, although their styles were different, drew the same type of men as Rex. Their gay gaze was fraternal and complementary. Domino’s grafitti-like scratch-and-sniff scribble style created fantasy men sketchier than Rex’s pointillist men. While Rex drew Rex men from his idealized imagination, Domino sketched realistic blue-collar Joes from his working life. Rex drew homomasculine men. Domino drew straight men. He told me about his Rex-like harvesting of seedbearers in Drummer 29, May 1979: “Right now, I’m trying to instill in my memory the face and greasy work clothes of the manager of a certain New Jersey Amoco station. I’m determined to get him alone one of these days, so that I can memorize the rest of him.” More verbal than Rex, Domino added the mixed dimension of graffiti-dialogue balloons — worthy of a Kilroy in a toilet stall in a bus station — inside his S&M frames to narrate his drawings. Rex, who did not speak until he was four years old, knew his pictures spoke volumes and were beautiful beyond words.

Rex had a special regard for his friend, San Francisco artist Chuck Arnett (1928-1988), a founder of the Tool Box bar (1962), whose mural on the cement stone wall behind its bar had been published in Life magazine, June 26, 1964. At that culture-quake outing of gay masculinity, Rex, the new kid in New York, was twenty years old. Sixteen years later in 1981, he spoke of Arnett when, after the fire, he was so desperate to get his drawings into gay rags to spur mail-order sales that he agreed to be interviewed for a feature I was writing about him for Skin magazine, volume 2, number 6.

Rex: I like Chuck Arnett very much. I think he’s too strong for the mainstream of gay appreciation and he’s probably best known for his Red Star Saloon poster [1972] as well as his works at the Ambush Bar.

For October 17, 1990, Rex drew the ad poster for the Lone Star Saloon’s first Anniversary Earthquake Party, celebrating the bar’s destruction, survival, and move to a new location — from 1099 Howard Street at 7th Street to 1354 Harrison — because of the October 17, 1989, Loma Prieta earthquake which also destroyed the Drummer office. Cued by the name of the Lone Star, he drew a red star (one of the few splashes of red in Rex’s black-and-white drawings; often reproduced as a white star) raised high on the long arm and fist of a leatherman that was homage to Arnett’s famous Red Star Saloon poster, and to the red, black, and white of the Nazi flag.

Rex: I think Arnett is the only true American fine artist with any track record in the homoerotic world. That man can lay down pastels like Renoir and not compromise the strength and raw sexuality one bit. Very immediate stuff, never lets his technique get in the way to shortchange his content or, more important, his audience.

Later in the interview, he assayed Tom of Finland and offered his Rexian theories about gay art, entertainment, and class prejudice.

Rex: Tom of Finland is the father of this business. There’s never a sense of degradation or tawdriness in his characters. There’s never anything sleazy about Tom’s creations.

Jack: Some critics consider your men sleazy.

Rex: My men are working class. If critics see that as sleazy, perhaps they have a class hangup. My working-class heroes are sweaty real reflections of life. Gays confuse the definition of sleaze. Real men aren’t sleazy. There’s actually something rather pure about the dirt and sweat earned from honest labor. The stink of the working class is quite different from the self-indulgent stink of laying about in a bathtub in the backroom of a gay bar. The homosexual fascination with filth is based in part on a deep-seated conflict and fascination with the working-class background. In its origins, filth came from honest labor, hence honest emotions, hence honest people. As opposed to make-believe [bar] filth that is “applied” rather than “earned.” Yet another fantasy of pretend sweat and dirt. Hence, pretend people.

Each of Rex’s contemporary artists was a star with his own passionate fans. But no artist scares the horses the way Rex’s intensity challenges the politically correct vanilla gay gaze. Some “artistes” are artists and some are entertainers. With entertainment, you get exactly what you bargained for. With art, something you might not have expected happens. The artist, like Rex, confronts you. You look. You see. Your way of seeing begins to change. You change. Your dick as a medium of magical thinking rises up like a magic wand that channels you forward into unexpected mindsets and sex trips you had no idea you were going to like so much. In Freudian terms, middle-class Super-Ego values taught by your parents slip another notch sideways toward your sex-driven Id and the strange men whose candy and rides you were warned about.

Jack: When you speak of other gay artists, what do you mean?

Rex: By the term gay artist, I don’t mean the window dresser at Macy’s creating flower pastels on weekends, or the tidy lesbian making abstract sculpture in her garage. I mean people who have directly undertaken the terribly difficult chore of portraying the human form engaged exclusively in homosexual acts or the homosexual lifestyle. These are the artists to whom I direct my criticism.

Jack: The marketplace here in New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Europe, seems suddenly flooded with these gay artists of whom you speak. Nude and copulating forms seem everywhere.

Rex: Yes. And I find most of them have everything going for them but one vital ingredient: no real sense of real male sexuality. Much of their work is heavy in technique and low on originality, content, and realism.

Jack: From years of artists submitting to Drummer, I’ve noticed that instead of drawing authentic pictures based on the sex they’ve actually had or seen, many of them base their pictures on other pictures. Like Tom’s. Like yours.

Rex: Ersatz sex. Erotic art without sex is like light without heat. Porn needs sex. If an artist lacks the facility to communicate real sexuality, then he should go into interior decorating, or portrait work, where his skills — and feeling — can be put to better use.

Jack: You use the terms erotic art and porn interchangeably.

Rex: I prefer porn. There are no doubts as to its intention. It’s like coining a four-letter Anglo-Saxon word from the Greek. Sometimes I say erotic art, but I prefer porn. That makes you stand up and be counted. Also, fanatics don’t attack erotic art with the same verve they’ll censor porn. And of course the word art intimidates all Americans. We all know we’re suppose to “revere” art and “hate” porn. Aren’t labels convenient? People naturally get confused when one is the other so I like to interchange them frequently when discussing these things. It keeps people thinking.

Jack: As an artist, are you a pornographer?

Rex: I certainly hope so! Otherwise I’ve got a lot of explaining to do to myself as to where the 1970s went.

Still, porn — like beauty — is in the eye of the beholder. In reality, much of the sex in my drawings is more ritually suggested than actually portrayed. But the end result should cause a hardon for men who like men. Really like men.

To be clear about Rex, one of the main purposes of erotically-charged gay art from toilet walls to museums is masturbation. Tom of Finland and other one-handed artists like Laguna surfer Skipper aka Glen Davis (1944-?), who drew for Drummer 15 and 186, talked of their process in connecting their penis-to-pen hardons to their viewers’ hardons. Tom said, “If I don’t have an erection when I’m doing a drawing, I know it’s no good.” Skipper added, “My drawing starts in my dick and the drawing’s done when I cum. This can take hours.”

Rex explained on his website:

It’s all about the penis. The penis in all its varied “states” grabs your attention as little else does in life, If only for the fleeting moment of recognition and revulsion it takes to turn away from it. So the penis as “image” really does have the potential to emotionally and physically fulfill the maxim that art should “move you.” In the case of pornography, the artist is presented with the option to literally move his viewer with “physical” results that few other art forms can match, bang for the buck…. It’s a win-win for both the artist who gets creative satisfaction from creating it, and an audience that often gets delirious “satisfaction” from viewing it.

Jack: You often load whole feature-length movies into the content of your single-frame drawings. Your realism, intensity, and content all turn some guys on and others off.

Rex: Yeah. Just like real life.

Jack: But aren’t you possibly too tough…too masculine?

Rex: One can never be too masculine in my book. But make sure you’ve got the right definition to that word too.

Jack: Why have you so defiantly devoted your considerable talent to porn as opposed to art?

Rex: I wanted to contribute something I felt people needed. It seemed to me the world didn’t need anymore portraits, still lifes, automobile ads, or clown faces. It seemed to me there was never enough porn. Then too, I like to think that porn separated the men from the boys. Art for me was too similar to entertainment, which in turn amuses you. Porn on the other hand — good porn that is — can shake you up, attract or repel you. True art has the ability to move, to change. But, on the whole, I think people dislike art because in reality they dislike being changed. Porn on the other hand asks nothing other than that you enjoy yourself — so powerfully that it actually changes a physical portion of your body from soft to hard. Perhaps porn is a kind of Super-Art. In my case too, porn allowed me to present a “type” of man who is perennially out of favor with the artistic “set” who find a nemesis in the hard-assed working-class hero.

Jack: How ironic because so may of them fancy “Marxism.”

Rex: I think for gay men to have so underestimated the working-class male is very wrongheaded.

Unlike many published gay artists, Rex studied anatomy and was an intentional flaneur and voyeur of men on the streets. He was a Platonist in search of ideal body parts, making a fetish of classic chins, cocks, feet, and hands. Like Charles Atlas selling muscles in comic-book ads and Dr. Frank-N-Furter creating custom-made hunks in The Rocky Horror Show, in just seven days Rex could make you a man.

In 1984, during an afternoon picnic Mark Hemry and I hosted in our backyard for our friends David Hurles, Robert Mainardi, and Trent Dunphy, Rex, in an impromptu anatomy session asked me to put on my leather jacket to pose positioned with my wrist just-so, coming out of the sleeve, because he needed to make a Polaroid reference photo so he could sketch the exact angle of bone and flesh for the last tiny detail in his drawing “Pigsticker.”

Reversing the camera on Rex to shoot him for a reference photo was farcical. His longtime friend, tattoo artist Robert Roberts, told me about Rex’s reticence in terms of Roberts’ photo, “The Red Line”: “As you know, Rex adamantly avoided being recognized. He did, however, let me photograph his hand holding my grandfather’s plumb bob, then got all concerned that someone would recognize that it was his hand.”

In Summer 1987, Rex wrote with charming candor about his work and his marketing.

Dear Jack, As a follow-up to our conversation the other day, I’m enclosing the following items. 1. A copy of my present brochure, which you may or may not want to send out to your [Palm Drive Video] customers… 2. Here are some new works I don’t think you have. You may have seen them in censored versions in Drummer or Inches. It was just about a year ago [Summer 1984] I was up at your place with Bob and Trent and I made you pose with a leather “arm” for my “Pigsticker” drawing. So here’s a print of the finished version.

Also, the “Cigar Face” [modeled on boxer Chuck Wepner] which I thought you’d like (another?) print of…. I’ve spent my whole year trying to develop these new “bum” faces — up to now it’s been hit or miss, close but not perfect.

In these last two drawings [in his Armageddon series whose shocking “Rex Man with Pan, the Goat” on the cover had to be censored and replaced with a Rex man hovering over a skull with a knife in its mouth while the Rex man sets fire to $50 bills.]…I’ve finally hit the mark; got JUST what I wanted — no more, no less. I think the face on the cover art (burning the dollar bills) comes the closest to these new faces, but even he is not truly focused as are these new ones.

I always got good customers from David’s [Hurles/Old Reliable Video] mailing list; his photographs seemed to appeal to a type that would also like my drawings. I think your people [Palm Drive Video customers], off the beaten path, would also find them interesting. Write and let me know, or phone to speed things up. Best wishes, Rex

Rex was a good writer, an astute critic, and an intriguing artist-in-residence with his patrons and friends in San Francisco where in 1985 Mayor Dianne Feinstein controversially named him as one of the City’s one hundred most influential artists. In 2005 in our little on-again-off-again Bloomsbury, he wrote the introduction to Speeding: The Old Reliable Photos of David Hurles. To his dying day, Rex complained that his erstwhile friend David (1944-2023) never thanked him. Rex, like Shakespeare’s Iago, knew how to carry a grudge — even after David three years later suffered a drug-induced stroke in 2008 and spent fifteen nightmare years disabled in assisted living. When David died on April 12, eleven months before Rex, the man who kept an active frenemies blacklist, wrote,“My introduction to Speeding was eulogy enough for him to whom I haven’t spoken in thirty years.”

For twenty years from 1990 to 2011 when Rex made his escape to Amsterdam, Mainardi, author of Hard Boys: Gay Artist Harry Bush, and art collector Dunphy provided Rex with his own Larkin Street studio on the private second floor above their beautiful “olde curiosity shop” and photo archive where for fifty years they bought and sold collectible vintage erotica over the counter of their storefront, “The Magazine,” at 920 Larkin in the Tenderloin. In 2016, as art patrons devoted to preservation and history, they donated their four-story building to house and archive the physique photography and art of the Bob Mizer Foundation.

In 2012, Bob Mainardi (1946-2021) wrote:

Rex is one of the foremost artists of forbidden and politically incorrect sexual activity among men. His is more than merely “Gay art.” Rex the artist is a historian, a voyeur, a muckraker, and a trouble maker, a provocateur, a sensualist and a hedonist, the sensitive and observant portrayer of a secret world…. The world of leather and denim, steamy basements and grimy garages, anonymous sweaty tops and groveling sexpigs is perfectly suited to his black-and-white detailed and moody pointillistic renderings.

Rex, who had a mouth on him, told me Bob’s favorite artist was the Hun whom Rex did not like because the Hun could draw in two days what would take Rex two years. “I’ve analyzed this,” Rex said. “I’m jealous that the Hun can crank out the work so fast, really jealous of that. Then I justify it by saying the Hun’s work isn’t that good, but I don’t think that is just. A lot of people like his work. It’s very popular, more popular than my work today. He’s worked very hard at it. It’s work I’ve never liked. I think my work has a lot of taste. I’ve devoted my life to raising the standards of these things so that people will take it seriously. The Hun’s comic-book mindlessness to my eye — it might seem catty — but in a nice academic sense, it is just mindless. I think he’s a lunatic. So many young people are drinking him in and fashioning their fantasies around him. I see it as really detrimental. So many people prefer his work over mine, and I look at them and wonder.

“The Hun felt he was superior to me in language and everything. The weekend I was with him, well, I’m very forthright and rowdy. I talk a lot and use gutter language. He doesn’t talk like this. We drove around and whatever reaction I might have had to something, he would have just the opposite. It was like dragging a little old lady around. ‘Can we go to Knott’s Berry Farm?’ and ‘I can’t go out in the sun.’ And I’m thinking, this man is shoveling piles of piss on tortured campers? It just struck me as psychotic. I’ve had nothing to do with him since. He’s always tried to be very friendly to me and I’ve been very cold toward him.

“Bob here at the store,” Rex said, “is an intelligent man and sees it all, you know, but he’s also very naive, had a very sheltered sex life, hasn’t had the opportunity to do the things you and I did. He doesn’t relate to my work. To him it is unrealistic. I’ve had many people come up to me and say, where do you get these wild ideas? Even those medical things? Things, real things, that have actually happened to people.”

In 1981 I asked Rex, who so often drew from photographs, what photographers he admired.

Rex: There are two. Bob Mizer of Athletic Model Guild in Los Angeles has been photographing men for his AMG Physique Pictorial since about 1945. Nearly every man in America has come out on the subtlety of Mizer’s catalog of young American toughies wrestling in oil and posing in jockstraps, hard hats, and bodybuilder briefs. I think the brutal honesty of his lens is devastating in its ability to capture the quintessential sexuality of males as they “present it” to one another. His photographs are as unadorned as a passport photo with an immediacy which belies the fact they even are photographs — we see rather only a slice of life. For that reason, and because these are not “pretty” pictures, he has been overlooked by the gay media in general.

Jack: And the second photographer you admire?