by Jack Fritscher

How to Quote from this Material

Copyright Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. & Mark Hemry - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

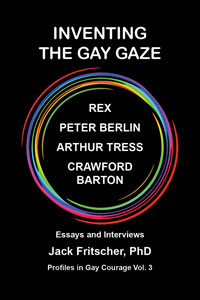

A Memoir of Essays and Interviews

Profiles in Gay Courage Vol 3

ARTHUR TRESS

Tressian Homosurrealism

“My gay life shapes my art.”

A Living Master of Photography

At Millennium's End

in Conversatioin with Jack Fritscher

April 20, 1999

Arthur Tress: Hello?

Jack Fritscher: Hello, Arthur. It’s Jack. How are you?

Arthur Tress: OK. Is this connection clear for you?

Jack Fritscher: Fine. How are you feeling? Your morning’s gone well?

Arthur Tress: Yes. I took a nice walk on the ranch out here [Cambria, California]. We have about two miles of ocean front. You’ll have to come down some time.

Jack Fritscher: Thank you. I’ve never been to Cambria. How long have you lived there?

Arthur Tress: About five years [1992]. I kept my apartment in New York for the first two years and then I gave it up to be here full time. Did you get that stuff I mailed?

Years later, in 2015, Tress moved to San Francisco to a home inherited from his sister, attorney Madeleine Tress.

Jack Fritscher: Yes I did. The clippings. The photos from your thousands of photos. Thank you very much. It was very interesting and I’ve spent the last few days brushing up on “Arthur Tress.” So today I should pretty much be up to speed on some of the mass amount that’s been written about you. Also, for some time, I’ve been working on a series of eyewitness books of oral history under the title Profiles in Gay Courage.

Arthur Tress: I see.

Jack Fritscher: It’s interviews with photographers like George Dureau, Crawford Barton, Joel-Peter Witkin, Miles Everitt, and Peter Berlin as well as curators like Edward DeCelle and critics like Edward Lucie-Smith. It may take years to assemble. I’m grateful to be able to include you speaking your unfiltered thoughts as the year, decade, century, and millennium grind to an end in nine months. I’m taping by the way so I can’t misquote you. Is that okay?

Arthur Tress: Yes.

Jack Fritscher: The first thing in my intent is to create text for a page or so of information about your forthcoming book [Male of the Species Four Decades of Photography of Arthur Tress, 1999, introduction by Edward Lucie-Smith], but the larger historical purpose is to record you speaking at this fin de siècle on your origin story, on your perspective on life, where you’ve come from, what you’ve tried to do, your reaction to the way the art world treats artists, and so on. So let me first ask your birth date. I figure it must be 1939 or 1940?

Arthur Tress: November 24, 1940.

Jack Fritscher: We’re the same vintage. You’re seventeen months younger. Where were you born?

Arthur Tress: In Brooklyn, near the Brooklyn Museum and the Botanical Gardens. As I child, I used to explore the Museum and the Gardens.

Jack Fritscher: Do you think those buildings, art and nature, had an effect on your work?

Arthur Tress: Yes, certainly. The Brooklyn Museum was like an old attic. It was kind of run down. It was filled with all of these Egyptian mummies, and it has an amazing ethnographic collection which is now more properly displayed, but in those years, it was just sitting in old cases. As a young child, I could just walk up the street and hang out there. Also nearby was the Brooklyn Public Library where I would spend a lot of time in the children’s library which was a WPA project and so the children’s library was huge and I would spend a lot of time looking at the illustrated books, art books, and things like that. And in the Botanical Gardens there was a Japanese Garden which was closed because of World War II, but I could sneak under the fence and I used to hang out there with some of my friends. It had waterfalls, but the waterfalls were turned off. I remember that we would play war games there, like hanging dolls and things on clothes wire, and we would play Hitler games and things.

Jack Fritscher: As kids during the war, we all played those kinds of war games, throwing rocks like hand grenades and yelling about Hitler and Tojo and “Bombs over Tokyo!” You were in kindergarten and I was in grade school when the war ended.

Arthur Tress: I just gave a lecture in Tucson and opened it up with a photograph of Cartier-Bresson [who corresponded with Tress] of bombed-out buildings in Hamburg which he took in 1946, and I was kind of wondering why I picked this picture out of all the Cartier-Bresson pictures.

I used to play a game with my sister. Even though I was a young child, three or four years old, the war did affect me. I remember playing Hitler prisoner games with my sister who would slap me as she “interrogated” me.

His photo, “My Sister and Father,” New York, 1978. When the honorable lesbian attorney Madeleine Tress (1932-2009) died, Arthur discovered 900 of his negatives from 1964 stored in her San Francisco home. He published 64 of them in his book Arthur Tress: San Francisco 1964 (2012).

Arthur Tress: But the reason I mentioned the World War ruins is that later in the 1950s the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, where I would hang out a lot, would have these paintings of these romantic surrealists like Pavel Tchelitchew [gay] and Eugene Berman [gay], and Paul Cadmus [gay] and they all used that imagery of ruined cities, bombed-out cities, and that affected a lot of my later work when I was doing the series about dreams. So I think that coming into childhood during that war period, even though we were far from the war, affected a certain kind of imagery that I was to produce in all those “bombed-out” buildings later on.

Jack Fritscher: How interesting. I was about to ask you about the special generation of us war babies. Any child who came to consciousness during World War II is a different kind of person than anybody who came before or after because the war was everywhere on radio and in newsreels at the movies, and we kids heard it and saw it and it terrified us even as we freaked over the images of the war: bombed cities, refugees, small children being tortured in the newsreels between double features of a musical and a western.

“Boy in TV Set,” Boston, 1972. At a time during the Vietnam War when sociologists claimed that violence on TV caused children to become aggressive and anxious, Tress said he created his powerful picture of a boy — sitting cramped inside the box of a broken television set with his big toy gun pointing out like a sniper from the missing TV screen — to make the point that media deliver violence from around the world to children who must somehow find their own defense.

Arthur Tress: Oh yeah, I’ve always had a fascination with photographs of concentration camp victims. Of course, being Jewish, I have a consciousness of that. My father’s brother was a rabbi and he saved a lot of European Jews bringing them to Cuba and to Mexico. He’s very famous for doing that.

Jack Fritscher: What was his name?

Arthur Tress: Michael Tress. Someone [Yonason Rosenblum] even wrote a book about him.

They Called Him Mike: Reb Elemelech Tress: His Era, Hatzalah, and the Building of an American Orthodoxy, Artscroll History Series, 1995.

Arthur Tress: He founded an important Jewish refugee kind of association [Zeirei Agudath Israel]. I bought a book by a German-Jewish artist who, well, I better not get into that because I don’t have his name, but that imagery of the kind of persecuted person, alienated in this kind of bombed-out landscape was something that was part of my childhood, of my family, and then in my high-school years, I started seeing this war representation on the walls of the Whitney and the Museum of Modern Art done by gay artists who were the popular artists of the time. This was before the abstract expressionists came in. So you had Cadmus’s famous painting of the sailors [“The Fleet’s In” (1934)], and some of his other works. Also Tchelitchew’s paintings of children in the trees where their faces are hidden. This mixed in with stage design from the New York City Ballet and movie design like the film An American in Paris where you had these very de Chirico kind of landscapes. These all shaped my early idea of art, but I think I was unconsciously relating to those paintings because I was gay, that sense of alienated molding that you had in high school, being a gay person in the 1950s.

Jack Fritscher: You and I came out in the worst decade to be gay in America in the twentieth century. You calculated that you became aware you were gay around the age of ten.

Arthur Tress: Yes. I played homosexual games with other boys, but I could sense they were growing out of that. We might jack off together, measure each other’s penises. They seemed to grow out of that, but I [Laughs]…

Jack Fritscher: …you made a life out of it, art out of it. When did you take your first photos?

Arthur Tress: Like all kids back then, I was given a camera when I was eleven or twelve. So I photographed my school trip to Washington, [D.C.], and things like that, but I really became a serious photographer when I was sixteen to eighteen and did amazingly mature photographs, many of which are just as interesting as the work I’m doing now. I was basically self taught. There was a little darkroom in the Brighton Beach Community Cultural Center and I learned to use that.

Jack Fritscher: Was your “eye” there in those first photos? Has it changed much since?

Arthur Tress: Actually, I go back and look at some of those early photographs. I had a little Rolleicord camera [a medium-format twin-lens reflex camera manufactured from 1933-1976]. And I would go out after high-school hours and roam around the abandoned summer housing, bungalows, and ruined amusement parks at Coney Island near my high school [Abraham Lincoln High School] and my home.

Jack Fritscher: So after school, you were outside instinctively cruising abandoned sites of the kind gay men instinctively cruise, and you were capturing images of your loneliness and estrangement as well as the fascination of the war imagery?

Arthur Tress: Yes. I would photograph kids in leather jackets who had pigeons on their roofs. I just recently did a photograph at the house of a model who had just finished college here in San Luis Obispo. I went with my friend Kevin and wanted to photograph these two college kids together. They had a microscope.

Jack Fritscher: I know the picture.

Arthur Tress: And the microscope reminded me that was the way I would try to seduce boys in high school. I would get them to give me a sperm sample and we would look at the sperm through a kind of toy microscope.

Jack Fritscher: You were already looking at life, framing life, focusing on life, through a lens.

In his photo, “Elmer Looking at the Brooklyn Bridge,” 1977, Tress shoots his camera past an obscured profile of Elmer’s head as Elmer peers down from a great height on the out-of-focus faraway bridge through a big magnifying glass in whose eye-like circle the span is in focus.

Arthur Tress: Yes. [Laughs] The sperm looked like tadpoles squiggling around.

Jack Fritscher: What boy doesn’t look at his sperm to see if he can see it moving, or see babies in it. I know I did.

Arthur Tress: [Laughs] I was very good at subterfuge. I just looked at XY Magazine and they have a sports issue with all these photographs of gay teenage athletes — runners, swimmers — it shows their names and schools. They are all talking about coming out in high school. They are practically campus heroes. They get elected prince of the year. It is so different from my experience. Some of them had anti-gay trouble, but…

Jack Fritscher: The world has changed. Guys now make sex “work” for them.

Arthur Tress: It’s really wonderful. It brought tears to my eyes to read that. They are going to have their own set of difficulties, of course.

Jack Fritscher: Everybody does, but at least being gay may no longer be the prime issue. This change may create a different kind of gay boy and gay adult, may even change the face of gay art, because of that inclusion in society. Gay art is often based upon alienation and resistance and the otherness of being other. I recently dug out some photographs I shot when I was fourteen. What amazes me is that the angles I use as an adult were already present. It sounds like you find the same thing. Certainly, you, as a Jewish boy during and after World War II, experienced disintegrating worlds when you visited the shuttered Japanese garden ruined by war — and the summer houses in ruins. That kind of set the stage for your gorgeous work of gay men cruising the surreal ruins of the Christopher Street Piers where you caught us all like the endangered folk culture you shot in Appalachia.

In 1968, ethnographer Tress had his first one-person exhibition Appalachia: People and Places at both the Smithsonian Institute and the Sierra Gallery in New York City. Appalachia: People and Places was one in his inter-related series including Open Space in the Inner City; Shadow; and Theater of the Mind.

The Christopher Street Piers jutted west out over the Hudson River at West 10th and West Streets in New York. Tress also shot closer to his home preferring the piers at 72nd street near the abandoned Railroad YMCA with its 200 rooms where he took models for more privacy.

In the way that sex in Samoa and New Guinea fascinated anthropologist Margaret Mead, and the Dust Bowl fascinated photographer Dorothea Lange, the piers, in that first decade after Stonewall, were an irresistible magnet of human behavior for photographers wanting to turn the free photo-ops of raw promiscuous lovely sex into art like the pier peer-group of Arthur Tress, Frank Hallam, Leonard Fink, Peter Hujar, as well as David Wojnarowicz whom Tress introduced to the piers on a night-time tour in 1978.

Jack Fritscher: Yet, in the context of the queer space of those abandoned piers, the decade before AIDS, you filmed a flourishing, vibrant, haunted life of sex that’s now gone with the wind. First you shot empty ruins, then people in the ruins. As you grew up, did you change your angles, your way of holding the camera?

Arthur Tress: Actually, my photography has always been fairly straight forward. I tell my students, “Make the picture. Don’t censor yourself about what’s a good picture and what’s not.” I’m sorry that you don’t have my Stemmele Monograph [Peter Weiermair, editor, University of Michigan, 1995]. The first four pictures in the book are pictures I took at Coney Island when I was sixteen and seventeen. It’s mostly that I set up little still lifes. The photographs also have kind of a dark melancholy about them, a very surreal feeling, and that’s what’s been pervasive in my best work until now.

It’s kind of interesting that surrealism really started in 1910 with de Chirico [Giorgio de Chirico, Italian, 1888-1978]. He was a gay man and later the gay scene became more evident in his paintings, but he always had these great long vistas with a great chimney or a factory chimney looming at the end of the arcade or a bunch of bananas. There were always these obvious phallic symbols. It was quite amazing. Within a short period of time from 1910 to 1915, he created these great “metaphysical paintings” which he called them — and then false realism grew out of that, although the French made it very heterosexual later on. Everyone has just taken his themes. The people who collected him were mostly gay.

Jack Fritscher: The passionate few create classics.

Arthur Tress: Yes. I’ve had encounters with one of them named Monroe Wheeler, at the Museum of Modern Art. [Monroe Wheeler, 1899-1988, partner of novelist Glenway Wescott, 1901-1987] Most of the curators and administrators who were running the Museum were gay in the 1950s. So there was always a very gay sensibility in that world.

Jack Fritscher: I find your sense of figure in the landscape to be, in filmic terms, very akin to the loneliness of Antonioni, the gay men lying on the beaches with the whales or seals in the background. You capture a certain kind of 1960s international filmmaker “look” like Fellini in the last scene on the beach with a sea monster in La Dolce Vita [1960]. Your photo of two boys — one on a rock, the other standing over him.

Arthur Tress: Yes. Both are wearing scuba-diving face masks [“Spear Fishing,” Florida, 1976].

Jack Fritscher: It’s a gladiatorial image out of the Colosseum where the phallic “trident” is pressed down against the bare chest of the vanquished boy by the victor. The sea water below them looks like it could be from Roman Polanski’s Knife in the Water (1962). These images, the frames you design, oftentimes look like stills from a larger Arthur Tress movie I’d pay to see. You are a filmmaker.

Arthur Tress: I think a very formative period was my college years when I ran the film program at Bard and chose the films for our Saturday night screenings.

Jack Fritscher: I was doing the same teaching university in Michigan.

Arthur Tress: It doesn’t say so on my biography, but after Bard College [Bachelor of Fine Arts, 1962], I immediately went to film school in Paris for a couple of months and have made some films.

Jack Fritscher: It shows.

Arthur Tress: Yes. Probably an even earlier effect on my photography were the black-and-white films of [photographer Irving Penn’s brother] Arthur Penn [The Miracle Worker, 1962; Mickey One, 1965] and Elia Kazan [A Streetcar Named Desire, 1951; On the Waterfront, 1954; and America, America, 1963].

Jack Fritscher: When you mentioned “pigeons on the roof,” I thought of On the Waterfront immediately.

Arthur Tress: Definitely, because those were the films that we saw as teenagers, like Rebel Without a Cause that had homoerotic overtones because of Sal Mineo.

Jack Fritscher: And because of James Dean’s own homomasculine image in the 1950s, as always, the worst American decade for being gay — when you and I were teens — and both straight men and gay men were butching up their own masculine and homomasculine images as gender declarations. I notice in one of your later photographs you picture a man leaning against a wall on which hangs a poster of James Dean in Rebel.

Arthur Tress: Oh, that’s the director of the film.

Jack Fritscher: Nicholas Ray.

Arthur Tress: Yes, he was living as a kind of alcoholic in the East Village in a tenement apartment. I read recently, it might not be true, that he was having an affair with Sal Mineo.

The bisexual Ray reportedly had sex with teens Natalie Wood and Sal Mineo and some sort of “relationship” no one wants to “recognize” with James Dean. My own feature article on the seductive eros of the closeted James Dean was published in 1961.

Jack Fritscher: The way you pose Nick Ray up against James Dean’s photo is such a succinct juxtaposition of existential decay. He is very much identified with the creation of the iconic 1955 James Dean image. He even looks a bit like James Dean in ruins, as James Dean might have looked had he lived a long dissolute life like Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray.

Arthur Tress: Time makes ruins. The camera helps organize the chaos.

Jack Fritscher: And clocks. You often include clocks in your work [“Electrocution Fantasy,” 1977; “Blue Collar Fantasy,” 1979; “Elmer Inside Clock,” E.H., 1978], but the “clock of the body” is something that you use so well in showing a trajectory from very young people to very tender older men like your father. May I say your pictures have added resonance now because of the incredible speed trip of aging that occurs with AIDS. Your historical photos have become mourning tableaux of lives now lost.

Arthur Tress: Actually, I did my Hospital series [in an abandoned hospital on New York City’s Welfare Island aka Roosevelt Island] in the mid-1980s. Around 1983, I stopped shooting models for ten years while AIDS happened. I only began shooting models again in 1993 after I moved to California.

Jack Fritscher: As the epidemic was growing worse. I wonder if your boyhood microscope experiences, counting sperm, might have been the beginning of your inclusion of technology in your photos.

Arthur Tress: Oh, I hadn’t thought of that. It might be there. [Laughs] That’s interesting, yes, that could be there.

Jack Fritscher: An artist intends certain things in his work, but once the art object exists, it exists independently from the artist in the eye of the beholder. How do you feel about people interpreting your art?

Arthur Tress: I find that my best photographs are metaphorical or allegorical and the more interpretations and feelings that people can bring to them, the better. I’m always very pleased with that. That’s why my photos are purposely ambiguous.

Examining a Tress picture some time ago, my husband of forty-five years asked me if I was one of the two men in Arthur’s capsized telephone-booth photo, “Secret Conversation,” New York (1980), part of his Facing Up series. He who knows my face said, “Is that you? That’s you.” In the 1970s, we all looked alike, leading parallel lives, sporting porn staches and clone crewcuts; but as best as I can recall from those hazy golden days of sex, I wasn’t in that photo, even though the man sitting shirtless in the corner reading a book looks exactly like my look then when I first published Tress’s pictures. To my eye, it even “feels” like me, like something that happened in a forgotten dream which makes it perfectly Tressian. It’s not me, but do we all see ourselves emerging in the gay mirrors of his photos? The uncanny resemblance in this 1980 picture can be vetted against the portraits Mapplethorpe shot of me and him together in 1978.

Jack Fritscher: And that ambiguity is one of the beauties of your work because it allows the person to see what you are doing, and what your model is doing, and then — thesis, antithesis, and synthesis — take it to heart and enlarge upon it personally.

Arthur Tress: Yes, I do usually get specific feelings, inspirations, from the model and the location. I do try to include from their input some little psychological [narrative] “clues” when I can.

Jack Fritscher: I think that, like Robert Mapplethorpe, you transcend literal S&M and its conventions and make its rituals something transcendent, something metaphorical. Could you explain how you went from playing Nazi war games to seeing S&M emerge in New York at the piers and in the bars?

Arthur Tress: Actually, I never really participated in sex or S&M on the piers. I’d go there during the day because there was light to shoot. It could be a little dangerous cruising through the ruins at night.

Jack Fritscher: When you could fall through holes in the floor and drown in the Hudson River.

Arthur Tress: Even so, day and night, lots of guys, sailors, for instance, would be cruising and having sex, but everyone wasn’t involved with S&M.

Jack Fritscher: I’m thinking of your many photos of leathermen. Instead of outright S&M, perhaps your photos capture the kink of sex, of domination and submission.

Arthur Tress: I’m very interested in images of things being tied and bound and meshed and the feelings that you get from that.

Jack Fritscher: What feelings are you going for?

Arthur Tress: Well, it’s a combination of a kind of oppression with an escape to liberation in the background. There is one photograph where I tied up a model wearing Calvin Klein underwear — and that I did enjoy doing. I’d never done that before. It was recent. So I probably am a closeted S&M person.

In Tress’s “I Dreamed I Was Fit to Be Tied in My Calvins,” 1995, a nude male figure lying on a disheveled mattress stretches out full length tangled in a bondage of a long winding cloth (like the linen cloth with which Egyptians wrapped their dead), and almost a dozen pair of white Calvin Klein underwear — a gay fetish like jockstraps and condoms — slipped up his legs, hobbling him, with one pair masking over his face with his eyeglasses on the outside of the underwear. The title spins the popular 1960s ad campaign for Maidenform Bras meant to support women liberating themselves with the ever-changing tag line: “I dreamed I…(went back to school, won the election, etc.) ….in my Maidenform Bra.”

Jack Fritscher: Perhaps you are. And more out than closeted. Personally, you may not be involved with S&M, or approve of this label, but your fans, especially Drummer magazine readers, find you to be an iconographer of S&M.

Arthur Tress: Yes, on a subconscious level, I guess I am. I did write a little essay called “Blue Collar Fantasy” for an image [The Book Dealer] from my first book. It’s a man dressed in a suit standing and reading a ledger book spread out over a nude man [in a hard hat lying on his back] on the desk in a kind of Michelangelo pose.

I used to take my portfolio [his ledger] around to art directors [in suits] so they could see my work. You realize the power situation [of the business world of art] and just realize the S&M undercurrent of everyday life. That to me is very interesting where you’re getting all kinds of plays on power and exploitation.

Jack Fritscher: Of course, but is that what S&M is? Isn’t S&M sensuality and mutuality also? And sex and magic? Maybe there is an essential nexus between your photography, your high-school experiences, and S&M. In many ways, male S&M is the acting out of coping rituals that through magical thinking transform the bullying in high school into fun in the dungeon. I read you once said, “A photographer could be considered a kind of magician, a being possessed by very special powers that enable him to control mysterious forces and emerge outside himself.”

Arthur Tress: Oh, I see.

Jack Fritscher: You seem to find something heroic in suffering, in masochism. In terms of Western culture mythology, you could be illustrating the Martyrology: The Holy Roman Book of the Martyrs. You have a very, maybe Tarot-like, maybe Christian, picture of a man hanging upside down in a cruciform position on a ladder near another man almost in shadow who is holding a pointed spear in his fist. It looks like he’s getting ready to pierce the side of the inverted crucified man like the Roman soldier with a spear stabbing a hunky Jesus crucified on Golgatha. I appreciate how some very iconic Western culture images of transcendent suffering infuse some of your work.

Arthur Tress: I find a sense of anger in my pictures. It might come from sexual frustration.

Jack Fritscher: But you don’t strike me as angry. Are you sexually frustrated? Or do you mean frustrated by our puritan culture?

Arthur Tress: Well, I think for many years, I was frustrated by my experiences in high school. Now I’m older, the situation has improved. So when I’m working with a model, I think I am sometimes acting out a kind of erotic hostility that goes back to my teen years in high school. I think one of my erotic fantasies was I could have sex with my straight fellow students if they were sleeping or drunk or in some helpless state.

Jack Fritscher: You have a lot of “sleeping beauties” in your psychological surrealism where you play the handsome prince and kiss them with your camera to make them come alive.

Arthur Tress: So on one level I’m still acting out that teen fantasy as a sexually frustrated person. I don’t see these images of passive victims as negative images.

Jack Fritscher: Because you regard them like the high-school hero asleep or drunk and you get a chance to rub his dick.

Arthur Tress: Yes, well, that was the covert sexuality that was allowed to me in that period and I’ve been exploring that for many years.

Jack Fritscher: You have said that you thought S&M passions dramatized the darker side of the human condition, but perhaps this passivity of the sleeping beloved is almost like Michelangelo’s dead Christ being held reclined in lap of his mother in the Pieta.

Arthur Tress: Yes, or Michelangelo’s Prisoners, the standing sculptures where the figures are emerging from the marble.

Jack Fritscher: You have also said that you thought photography’s function was to reveal the concealed even if it was repugnant to society. What do you think you are revealing in these photographs, overall, if you just had to capsulize your career in terms of the specific concealed thing that you are revealing?

Arthur Tress: I would say, when I’m really getting down to it, I try to release all the inhibitions around a subject. My own and society’s.

Jack Fritscher: So you’re trying to release inhibitions so that people can see inside themselves or inside the human condition?

Arthur Tress: Yes, but recently I’ve been thinking about a title for my new book. I was sitting around with friends and they came up with the title Constrained Silence.

Jack Fritscher: Sort of Bound and Gagged [the gay S&M picture magazine published by Bob Wingate’s Outbound Press, New York, 1987-2005].

Arthur Tress: Which sort of fits all the pictures. But I’m feeling a little different from that at the moment. There’s another metaphor for my own personal sexuality, and that’s as an artist you are taking chaos and giving it form. What I used to like to do in backrooms at bars was go up to men and reach into their button flys and get them hard, and I thought that was like the greatest thing and then I’d walk away.

Jack Fritscher: That was you.

Arthur Tress: That was me. I came up with this idea for a title because we’re using my photograph of the guy in the hot tub with his head emerging from the hot tub bubbles. [“The Deliquescence of Elliott,” 1995]

Jack Fritscher: With his eyeglasses and his two hands breaking the surface of the water, it’s a beautiful picture. His eyeglasses are steamed. He’s up to his neck in water, virtually blind, sightless, on the cover of a book meant for the eyes.

Arthur Tress: Yes, I hope we use that in the book. I thought of a phrase called Breaking the Surface as a title. Do you like that?

Jack Fritscher: Yes, I do.

Arthur Tress: So I’m thinking that this wonderful virile idea of penetration, of going into something, breaking a membrane, but also rising up out of the water in a “wonder” sort of phallic way.

Jack Fritscher: You certainly feature a lot of water in your pictures on beaches, in bathtubs and hot tubs, in shower rooms. And you are not shy about male frontal nudity which is courageous in a culture whose ultimate taboo is penis.

Arthur Tress: It is interesting how accepted the female nude is. It’s never seen as erotic in the all-world setting, but the male nude…

Jack Fritscher: A male photographer and a female photographer can each shoot the same nude male at the same moment, but one photo will inevitably be labeled as gay and the other celebrated as brave and more acceptable.

Arthur Tress: I’ve had a forty-year shooting career. I spent four years from 1977 to 1981 doing my first group of male nudes. I spent another four years doing my male nudes here on the Central Coast. So 20-25 percent of my photographic career has been dealing with very specific gay male imagery. And, you’re right, it’s true that my nudes are usually glossed over a little bit in the retrospective catalogs and essays about my work. But if you consider my overall work, I think it is important to know about my nudes and my sexuality. We often know very little about artists’ sexuality. What did Picasso do in bed? What did Suzanne ever do? [Picasso’s 1904 “Portrait of Suzanne Bloch”] Of course, you know all that about your friend Mapplethorpe.

Jack Fritscher: Yes, we all know quite a bit about Robert Mapplethorpe. Been there. Done that. Loved it.

Arthur Tress: [Laughs] His official biographies don’t seem to mention what he was doing sexually with Sam Wagstaff, but they all like to mention how Robert and Sam collected American silver.

Jack Fritscher: Edward Lucie-Smith [British critic, born 1930] told me that Robert’s flowers have importance and cachet hanging in somebody’s dining room precisely because in the bedroom they have a fisting photograph. Perhaps your nudes also give frisson to your surreal catalog? Robert started out in the 1960s pasting up collages of other photographers’ nude work cut out of gay physique magazines he bought in adult bookstores on 42nd Street. He learned a lot that way.

Arthur Tress: I wasn’t doing that kind of collage work with male imagery. [“Father of the Bride,” collage, New York, 1983] I got to my homoerotic imagery through a different track than Robert. I started with my early high-school pictures of Coney Island, with a kind of alienated gay loneliness which is my work from the 1950s. You will get to see this when I send you my book. I’m lucky. I still have my teenage negatives in good shape and I’m printing them up. I have several of them as vintage prints. Soon after college, I traveled for several years in Asia, Japan, and the work became a little bit more documentary, photographing different primitive tribes, people in Appalachia. I loved having that opportunity to travel. I had really no sex during those years.

Jack Fritscher: Was there any moment of revelation for you staying with some tribe, some family, some culture?

Arthur Tress: Actually, I’ve written an essay about it which I can send you. What I learned from my experiences with different cultures is the metaphorical connectedness of everything in their societies, the way they were connected to nature, to each other, and the little huts and sculptures and their ceremonies. It all seems to be of one piece. Most ceremonies deal with cycles, the life cycle of youth to old age. You know, birth ceremonies, initiation ceremonies, death and funeral ceremonies, which is the way I usually like to structure my books. Even that little book you have goes from youth to old age. In the use of ritual and ceremony in these cultures, the people are constantly moving between different levels: from earth to heaven, from earth to hell, to the underground. There is tremendous cycling of movement to paradise or to hell. Then you have natural God and demonic God. So you see in a lot of my photographs that they are always striving to get into these alternate states. Among these people in their initiations of boys into men, I saw these wonderful elemental gestures of birth ceremonies in tribal initiations when men are dragged naked through each other’s legs and covered with feathers and blood and quite often semen.

Jack Fritscher: No disrespect to the tribes or you, but in pop culture how wonderfully Mondo Cane! All those ceremonies, all those rituals, reaching for the low, reaching for the high, every one of those primal things you mention seem akin to gay culture which is also very Mondo Cane. In fact, Drummer, the magazine of leather rituals of initiation which I edited for years, is very Mondo Cane.

Mondo Cane (1962) became a global box-office hit and a camp classic with its ethnographic travelogue scenes documenting taboo cultural practices around the world designed to shock movie-goers in scenes of tribal rituals of sex and death staged or creatively directed like reality televison shows to enhance the shock appeal. Its beloved Oscar-nominated love theme “More” won a Grammy. In the revolutionary 1960s, the transgressive High-Concept of “Mondo” Style encouraged the media “outing” of taboo subcultures like homosexuality and S&M, and stimulated the eye-opening and mind-blowing images of Warhol, Mapplethorpe, and Tress.

Jack Fritscher: Your work affords a lens of analogy that helps explain why gay culture is looked upon as something primordial and separate beyond the pale of our straight American culture holding its nose about homosexuality. For all your photos are, they are also often psychic windows into the gay soul revealing what is concealed in gay hearts, minds, libidos, and closets.

Arthur Tress: I was involved with several primitive tribes, Eskimos, Lapps, tribes in India, mountain tribes, people in Tibet, and they all worship the horned god. It was a kind of shamanistic northern Arctic culture. Every culture that I would visit would have great piles of bull horns with which they would decorate their homes, or the shape of their houses would be horn-like. [“Boy with Magic Horns,” New York, 1970] I was with one tribal group in India where once a year the young men of the tribe would wrestle with the bulls. They would let the bulls run in the streets, sort of like Spain. If they manage to grab the scarf off the horns, they get to marry the chief’s daughter, or something like that. These are very ancient rituals. I tried to join in, but the fascination of being gored in the ass by a bull, the idea of penetration, was actually very frightening.

Jack Fritscher: You literally ran with the bulls?

Arthur Tress: Yes. For about ten seconds. It’s very frightening, but at the same time very exhilarating. The bull horns also relate to the shape of the horned moon. When I did my book Shadow, there is a lot of bull and flight imagery. In fact, in that book I wear the mask of a bull and go into a bull’s ring. Do you have my book Talisman?

Jack Fritscher: No. You have so many wonderful books that this interview can perhaps introduce to new fans who don’t know where to begin with an artist as prolific as you. I mean in 1964, you shot a thousand photos of “pre-historic life” in San Francisco — before the Summer of Love [1967] and the rise of the gay Castro Street arrondissement [1970] — shooting the Republican Convention [1964], the Beatles concert [1966], civil rights demonstrations — and that’s just a fraction of your global career.

Arthur Tress: I don’t usually mention my books to interviewers, but I’m talking about them to you because you’re interested in my gay life which reflects on and shapes my art. That time I ran with the bulls was pre-AIDS. I was looking to get fucked, but to find a bullish guy to do that, well, you know how that story goes. So I turned to the arts around the worship of that animal. I found that kind of image in Picasso’s “Minotaur” in which a very voluptuous woman is sleeping all in white.

Jack Fritscher: Like your high-school jocks.

Arthur Tress: Yes. And there is this great beast with a bull’s head lifting the veil from her body. It’s very much the metaphor for the artistic experience.

I use the camera in a very aggressive way. I do. I don’t know Mapplethorpe’s process, but when I start to photograph, I’m very impolite as far as complimenting, “Oh, you look great!” I don’t do that. I yell at them. I do that for ten rolls, and I think by the tenth roll, they’re all looking very tired and anguished because they’ve been hanging upside down for an hour.

Jack Fritscher: Suffering for art. And willing.

Arthur Tress: My new theme is around an installation I’m doing with the working title Well of Sacrifice. It’s based on Mayan and Aztec sacrifice rituals. If you look at those Mesoamerican statues, they all have their mouths slightly open as if they’re inhaling. To me that is the ecstatic moment of the heart being ripped out, and you see that on a lot of the faces of my models. I say to a model, “Open your mouth.” My picture of the boy with the boat pressing into him? His is the sacrificial victim’s expression which looks the same as when you have an orgasm.

Jack Fritscher: This explanation will help anybody looking at your many books. I’ve a note I wrote here that “Many of your bodies look as if they were dumped in the woods by a weird serial killer.”

Arthur Tress: I know. We may use one of Thom Gunn’s poems that he wrote about [gay serial killer] Jeffrey Dahmer.

International British poet, MacArthur Fellow, and leatherman Thom Gunn (1929-2004) left London permanently for San Francisco in 1954 to teach at Stanford University. In his award-winning poems, he voiced the gay sensibility of motorcycle bikers, sadomasochistic leathermen, rough-trade hustlers, serial killers, skateboarders (akin to Tress’s book Skate Park, 2010), drug visionaries, and people with AIDS. His phantasmagorical books, all of which could be aptly illustrated by Tress, include My Sad Captains (1961), Jack Straw’s Castle (1976), Boss Cupid (2000), and his AIDS masterpiece, The Man with Night Sweats (1992). Having known Thom since 1969, I eulogized him in my essay (2019), “Thom Gunn: On the 90th Anniversary of His Birth, a Memoir of the ‘Leather Poet Laureate’ of Folsom Street and His Pop-Culture Life in San Francisco.”

Jack Fritscher: You stage and improvise so well within our weird popular culture. Thom Gunn is a good friend and I like your photo of him [“Thom Gunn,” San Francisco, 1995] sitting in his kitchen surrounded by a collage of photographs on two walls holding what looks like a comic cookie jar of the face of the Man in the Moon with his ceramic tongue licking Thom’s left nipple. It’s almost a Hamlet-Yorick homage.

Arthur Tress: Yes, that’s his collage [of hundreds of pictures of men].

Jack Fritscher: Which prominently includes Warhol Superstar Joe Dallesandro. You also capture Thom’s signature black panther tattoo on his right forearm [that was done by Lyle Tuttle].

Arthur Tress: You know, the other side of penetration is consumption. When I’m dealing with the male nude, I’m dealing with models. If I can, quite often I try to have sex with the model, towards the end of the shoot. Some I do.

Jack Fritscher: Did you have sex with Thom Gunn?

Arthur Tress: No.

Jack Fritscher: Thom and I first did the deed back in 1969 and have traveled together and been friends ever since.

Arthur Tress: I’ve seen the [1978] picture of you with Robert Mapplethorpe in your book. You were very cute.

Jack Fritscher: [Laughs] Everyone is cute when they’re young. I always thought Robert was cute. That’s why I tried to include cute unstaged candid pictures of him in my book, and not his dramatized self portraits. Do you ever put yourself into your portraits?

Arthur Tress: Actually, if you’re interested in my relationships to the model, we can get into this. I was going to write an essay on this — but I probably won’t — about how I usually meet my models and so on. Different photographers have different techniques for getting models. I’m a little shy about it. I just can’t go up to strangers the way Duane Michals does.

Duane Michals, born 1932, age thirteen at war’s end, widowed 2017, lenses his subjects in their environments and not in a studio. In the 1960s, he innovated shooting his still pictures like storyboard frames for a narrative movie or for a graphic novel as in his 1970 book Sequences. In 2019, Tim Sotor, a photographer friend of Michals who intentionally became friends with Tress, published ForTress (A Book about Arthur Tress by Tim Soter), a handsome insight into the personal Arthur Tress.

Arthur Tress: He really likes straight guys who I would be intimidated to ask because I would feel that they could sense that I was gay and might call me faggot or something, but Duane will just go up to a waiter or someone and take his chances. David Sprigle dares to photograph mostly the kind of straight young types that he finds around Venice Beach.

David Sprigle edited Male of the Species: Four Decades of Photography by Arthur Tress, 1999. In 2001, Tress’s Beefcake Plus exhibit opened at the Orange County Center for Contemporary Art in Santa Ana.

Jack Fritscher: That’s the gay ideal, isn’t it? The outdoor jock. That’s why [photographer] Jim French moved his Colt Studio [founded 1967] from cold Manhattan to the sunny beaches of Los Angeles. No matter what we say on the politically correct side, if you look at the gay classifieds, which are really the gay voice expressing the Id of its desires, they all want straight acting, straight appearing, straight males who won’t call them a fag. Or will. If that’s what they want.

Arthur Tress: It’s funny, most gay people today are so kind of “bland American” that they look straight to me. Very rarely do you see an effeminate guy any more. I mean, they’re not even clone-y types, but just average Joes, which I guess is the part of the ultimate resolution [of assimilation].

Part of the problem when I shoot gay men is that they’re more image conscious, more attuned to what is trendy or fashionable, than the straight models. They arrive knowing what they want to look like whereas a straight model is more a tabula rasa. Gay guys always have to construct an image to survive, so they’re always projecting an image. Sometimes it’s just awful because they’re just imitating posing for you right out of poses they saw in some magazine, but I use that too because that’s part of the process.

Jack Fritscher: Everyone wants to grow up to be a Calvin Klein underwear model.

Arthur Tress: So to pick up a model I’d go to situations where I think I’ll feel comfortable introducing myself as a photographer. I might go to a party and carry my photo book around with me as a way of getting to know men. I don’t feel that I’m that attractive or interesting on my own; but if I pull out my book, I can get people’s phone numbers. It’s a little bit of my personality that I feel that without my book and my photographs I’m not important or interesting enough to seduce or attract other men. I think every artist might also have those kind of feelings. You use your art to create more art and get attention. Perhaps fifty percent of any artist’s motivation, gay or straight, is to use their art to get attention and make themselves more attractive to other people. The two or three lovers I’ve had in my life are people who showed up at my lectures, or people I’ve met at my openings, because you get that kind of admiration that you can use as part of a seduction and building of a friendship. So I do that. Is this interesting to you?

Jack Fritscher: Yes, please. It’s the something new I’m seeking for your origin story.

Arthur Tress: So at events I will get their phone numbers. It does no good to give them your card because they will never call you back. In a week or so, I might call them and ask, “Are you interested in modeling for me?” I ask them what they do because sometimes that can be an interesting source for photographs. Like with the fellow who was a butcher — I shot that early image in a butcher’s shop. Or I’ll go to see what their apartments are like, if they have any interesting objects. Quite often, when I go to their apartment, I can find an interesting prop, like that stuffed sheep [“Man with Sheep,” San Francisco, 1974] or the microscope or something like the cookie jar for the Thom Gunn photograph. Thom and his roommate [longtime husband Mike Kitay] had a lot of interesting objects.

Or I may find an interesting location here on the Central Coast where there are not many abandoned factories or empty buildings, although I have found some. I have some models who are very good like this boy Kevin or Bob Rice who’s an older guy. Sometimes a model can be photographed many times, and some can only be shot once. With my early models, if they’re available, I use them again and again. What makes a good model is that they’re usually kind of athletic and they don’t just stand there. They’ll come up with ideas on their own. They’ll climb around things. Sometimes when I photograph a man who’s never modeled before, one of the reasons he might be doing it is that he wants to have someone photograph him jacking off. I probably won’t have any jack-off photographs in my book because they’re a little one dimensional.

Jack Fritscher: Not if you’re using a 3D camera.

Arthur Tress: But I do love to see them take off their clothes. Sometimes I volunteer to help them get hard, but it’s all for the purpose of playing together with them in this very creative, erotic experience.

Jack Fritscher: It’s the art of seduction you’ve been doing with microscopes and cameras since you were a boy.

Arthur Tress: Yeah, but it usually doesn’t make for very good photographs if it ends in sex.

Jack Fritscher: In other words, the sex has to go into the camera not into a Kleenex.

Arthur Tress: Yes. But sometimes if I’ve photographed a model for ten rolls of film, he’s been climbing a tree, and I’ve been hanging from a branch. It’s a little like the shooting sequence in Blow-Up [1966]. David Hemmings on the floor with the models. A bonding.

Jack Fritscher: We’re back to Antonioni.

Arthur Tress: Yeah, and Hemmings didn’t have sex afterwards with the models because he had a kind of creative camera sex with them while he was photographing them. Quite often, a shoot becomes a total experience in itself. For instance, when Kevin was climbing the tree, sex would enter only as an afterthought. But sometimes, if the model and I have created a sort of jack-off photograph, we’ll jack off together afterwards. At my age. I don’t try to impose myself too much on the model.

Jack Fritscher: People ask me all the time how can I keep shooting an erotic video with hot men sweating in front of my camera. They say they’d jump the model. You and I try to put the model’s personality and sexuality, and any sexual tension between us into the camera so it shows up in prints and on screen.

Arthur Tress: Yes. That happens. I’m happy when anybody will model for me for free and will sign a model release. So I’m happy to use eager gay models who know the score. I think I might even feel a little guilty about using straight models because I put their photographs into a gay context. However, when I shoot a straight model, like teenage runners, it usually makes a better-selling picture. [“Teenage Runners,” New York, 1976] I don’t know whether I should do that or not, but frankly I don’t feel too guilty about that. I show prospective models my photographs and books so they know what they’re getting into. I find there is a new generation that is generally bisexual. In fact, I think my last lover, Vince, is back living with a girl. Some young guys will start an affair with you to see what they can get, but others like you as a person and, being gay or bisexual, they are not so bound by the straight social conventions. They have a little bit more freedom.

Jack Fritscher: In your works, I spy themes of flight and fall. An Icarus equation. You suspend gravity. You stage people upside down, caught high up in tree branches, astronauts who fall to the shore, to the earth [“My Feet in the Air,” New York, N.Y. 1969]. I think of your remarkable photo of the boy sitting in the bath tub with the sailing ship. That could be the ironic cover of a twenty-first-century edition of Billy Budd.

Arthur Tress: Oh yes, that’s the title of the photograph. “Saint Billy’s Thesis.”

Jack Fritscher: That homage comes through so clearly. In the book I have the photo has no title.

Arthur Tress: That’s exactly what the title is meant to be.

Jack Fritscher: I know that we’ve discussed this personally, but your photograph “Squirt [Just Call Me Squirt, 1997] is a fresh new archetype acting up in an age of AIDS, a very hot and spermy shot of soda pop and body fluids that points in a happy direction. I also love the picture of the man in the truck cab filled with flowers. “Squirt” is one of the happiest pictures you’ve done. “Squirt” is certainly a joyous side of Arthur Tress. It’s a comic, vivid, and hopeful photograph.

Arthur Tress: I think we called that “Big Squirt and Little Squirt,” but we’re a little worried about putting it into the book because of the company owning the Squirt soft drink brand [Keurig Dr Pepper].

Jack Fritscher: But what an appealing ad. The slight blur of the nude athlete’s body behind the plastic “Little Squirt” statue offers some “modesty.” You may recall that Mapplethorpe appeared with [gay photographer] Norman Parkinson in a full-page ad in Vanity Fair [May 1987] advertising Rose’s Lime Juice for Schweppes.

Arthur Tress: That “blur” has a story. Back then, I had this young lover, Ben Sullivan, for three years, who’s also a very good photographer and like many of his generation, he’s in this kind of Nan Goldin school of photography.

Influenced by Antonioni’s Blow-Up and photographer Larry Clark’s approach to bonding with subjects living marginal lives, Goldin (born 1953) focuses on the queer LGBTQ underculture.

Arthur Tress: Ben’s photographs are much more loose and less structured than mine. He uses a 35mm camera and did all these kind of odd compositions. So while living together, he’d look at my work and I’d look at his work. He got me to loosen up a little bit in terms of incorporating accidental movement into my photographs. So there is also some purposeful blurring in some images.

Jack Fritscher: Which adds a ghostly touch. I think of your photo of a man being wheeled out of an intensive care unit on a gurney [part of his Hospital series] and you’ve caught him twisting his head in a blur from left to right.

Arthur Tress: Actually, that’s a picture I did for AIDS when there were only 2,700 cases.

Jack Fritscher: And that blur is there like a gay spirit soul exhaling and circling a stricken body like a grieving lover.

Arthur Tress: Yes. I’ve learned to relax more and be loose as in that “Squirt” picture because of living here in California in a house on the ocean where I have these very expansive open views while at the same time I’m dealing with some of these California models. This is a very different world from New York.

Jack Fritscher: Thom Gunn said the same thing of how his poetry loosened up after he moved from London to San Francisco.

Arthur Tress: Unlike Ben’s 35 mm, I do think its very difficult to catch movement with the Hasselblad that’s kind of clunky. When you press the button, the movement is already gone.

Jack Fritscher: How long have you used the Hasselblad?

Arthur Tress: Forty years.

Jack Fritscher: Our generation’s analog childhood has evolved to digital adulthood. Might you be changing to the new digital cameras?

Arthur Tress: No. I’m so comfortable with my camera.

Jack Fritscher: In the way that George Dureau shoots men who are amputees, you have men whose limbs you obstruct in certain ways or bend in certain ways that kind of reference broken classic ancient statues. You and he both fancy disabled men hobbling on crutches.

After I published four photographs by Arthur Tress in Drummer 30, June 1979, photographs by George Dureau appeared in two issues of Drummer: issue 93, April 1986, and issue 129, June 1989. In March 1991, my husband, Mark Hemry, and I traveled to New Orleans to shoot a documentary video interview with painter-photographer Dureau who was famous for his exquisite photographs of black men, ex-cons, and physically challenged men missing arms or legs. In 1996, three years before interviewing Arthur, when George and Mark and I were in Paris, the video documentary, Dureau Verite: Life, Camera, Canvas! as well as the video short Dureau in Studio were inducted into the permanent collection of the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Ville de Paris.

Arthur Tress: My poses are a bit like that. But whereas Dureau or Diane Arbus or Joel-Peter Witkin start with freaks and freaky things, I like to take normal people and make them look rather freaky and disabled, hovering on death. I kind of deform them on purpose. I think it’s more challenging to start with normality and make it deformed — or start with deformity and make it beautiful.

Tress’s contemporary, Joel-Peter Witkin, a World War II baby born a twin in 1939, began his career as a combat photographer documenting the Vietnam War. Born like the Jewish Tress in Brooklyn, Witkin, the devout Catholic son of a Ukrainian Jewish father and an Italian Catholic mother, often shot on location on Coney Island: “Puerto Rican Boy,” Coney Island, ca. 1956; “Christ,” Coney Island, 1967. In their similar themes, Witkin’s straight eye is a perfect match for Tress’s queer eye.

In Witkin’s 1982 photo, “Le Baiser (The Kiss),” he pictured two same-sex male heads kissing lips to lips in profile, but the heads that look like identical twins are actually one head cut in two for autopsy with the halves arranged face to face by the artist whose twin brother is the painter Jerome Witkin (born 1939). The photo created such an uproar that the negative was destroyed in 1983. Tress’s own photo of heads, “Platonic Friendship: The Last Symposium,” 1995, is two decapitated stone statue heads facing each other. The internationally collected Witkin is a recipient of the Commandeur de’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres de France. His books, like Gods of Earth and Heaven (1989), survey his work around the mythology of transsexuals, cadavers, and animals. When I interviewed Witkin in 1992, he told me: “Robert Mapplethorpe went out, as I do, into life’s darknesses. It takes courage not to be totally seduced by the dark. It takes courage to come back in, unconfounded by the darkness. Without the dark side of the soul, there is no saint.” In 2019, Soudabeh Shaygan published the case study, Mythoanalysis of American Contemporary Staged Photographers Works: Arthur Tress, Joel-Peter Witkin, and Gregory Crewdson.]

Jack Fritscher: You work so well with the textures of flesh and also the textures around flesh. For instance, your athletic bodies often appear caught in the incongruity of ruins of factories and piers and the detritus of the industrial age. Man in ruins. That’s as romantic as it is existential. In our high-tech age, you picture men almost back in the heart of the industrial age and the collapse of the industrial age. I so admire how you shoot so successfully on location. Mapplethorpe stayed safe in his studio with exceptions like shooting outdoors at the abandoned bunkers on the Marin Headlands which are like a mini-version of the New York piers. Like an avant-garde filmmaker, you march out with your models into the midst of nails and screws and the falling down structures of our civilization.

Arthur Tress: Because of that, I got arrested for the first time. For lewd behavior. It cost me $1,000. I had to get a lawyer for the model. But it’s a great picture.

Jack Fritscher: Where were you shooting?

Arthur Tress: I thought I was shooting in a fairly isolated place at Cal Poly [California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo]. They have this area called Cal Poly Canyon that’s like a big nature preserve with a jogging path through it. That’s where I did the wonderful photograph of the boy lying muddy and kind of broken in the ruts of the road with the distant horizon [Road Kill series, 1974, a nude male lies in the deep ruts of a muddy curved trail]. We were doing fine until a girl jogger came along and reported us to the police. Actually, I saw her in the distance and I would have normally ended the shoot because I don’t want to have problems, but what we were doing to get the picture was so good, I knew that we would never get it again so I kept him there.

Jack Fritscher: That adds an edge of risk to your work that one doesn’t get in the studio.

Arthur Tress: Jack, I have to send you this video that deals with some of this stuff. These people made a half hour video about me around 1985. It’s called Arthur Tress. I talk about the male nudes for about five minutes in it, but it’s also when I was doing the Hospital series when I did fifty installations in the hospital. They were sculptures I made expressly to photograph them.

For five years in the 1980s on Roosevelt Island in an abandoned hospital with 500 rooms that Tress turned into his own pop-up studio and his own museum, he created “junk” sculptures out of antique medical equipment and spray-painted them to re-animate them to photograph them. As a folklorist, Tress says that descending into ruins he becomes like a shaman medicine man in an ancient tomb. For this project, he hand-made in situ hundreds of brilliantly colorful psychedelic mixed-media installations, very toy-like, very Willie Wonka candy-color palette, very Alice in Wonderland, very Disney Fantasia, very abstract to set-decorate hundreds of photos that preserve the “still life” installations that lasted only a few days and no one ever saw because of vandals and rain. It was his first serious work with color and some of the visual textures of the pictures suggest a pairing with the drip paintings of Jackson Pollock.

Arthur Tress: I like the decay and loneliness of industrial ruins. Like I’m cheating death with these little bursts of life. I talk about how I enjoyed it being a dangerous building and how I got very turned on by the danger and the fun of the danger, so I’ll send you this. Of course, now with Photoshop you can “place” a model anywhere.

Jack Fritscher: We discussed image manipulation at the exhibit in San Francisco where you were giving a talk, and I asked you during the Q&A if, because you make your installations and collages by hand, will technology be altering the way you work, and you said you didn’t really think so.

Arthur and I first met in May 1994 at The Male Nude Exhibit, Vintage and Contemporary Photographs by Paul Cadmus, Arthur Tress, Peter Stackpole, Biron, and Others, Scott Nichols Gallery, 49 Geary Street, San Francisco. Arthur was also represented in San Francisco by my friend Edward DeCelle at the Lawson Decelle Gallery (1972-1983), 80 Langton Street, in the bohemian SOMA leather district, South of Market.

Arthur Tress: No, because I can get the effects I want with very simple means.

Jack Fritscher: You do most of your bespoke effects [as in the Hospital series] hands-on before you shoot, not after.

Arthur Tress: Yes. I try to shoot my subject matter the way it exists. My friend, Richard Lorenz, went through my travel pictures and my Appalachia pictures, and he found hundreds of pictures of attractive, interesting men.

In 1994, Richard Lorenz published Fantastic Voyage: The Photographs of Arthur Tress.

Arthur Tress: So on an unconscious gay level [his gay gaze], I was photographing all these coal miners, sons, and workers, young guys in Mexico, whatever, catching their innate sex appeal. So Richard also put together a second little book called Male of the Species which he showed to some publishers, but it never really clicked.

So now I’ve my early documentary photography that became Open Space in the Inner City [his 1968 four-volume series] which pictured empty places where children could make their own parks and playgrounds in the city. I was photographing them and abandoned cemeteries and factories — these places where kids could make their own vest-pocket parks.

In 1970, the New York State Council on the Arts made Open Space in the Inner City, first exhibited at the Smithsonian and the Sierra Gallery in 1968, into a fifty-plate boxed portfolio in an edition of 1000 that was given free to schools and libraries.

Jack Fritscher: Are the photographs erotic in themselves or is eros in the mind of the beholder? People find sex in the underwear photos in the Sears Catalog. A fetish exploited by Calvin Klein.

Arthur Tress: You’re right. It depends upon the predilections of the viewer. For years, people have been photographing children as in Steichen’s The Family of Man [1955]. So my documentary photographs of children living in the ruins of the city became my project The Dream Collector [1972] for which I audio-taped children talking about their real dreams and nightmares, and then photographed them acting out some of those dreams like the boy metamorphosing into a tree while lying on his belly alone on a wet walkway with tangles of roots coming out of his sleeves [“Boy with Root Hands,” New York, 1971].

Jack Fritscher: Your “Arthurian Grimoire” of role-playing fantasy.

Arthur Tress: It was children being crushed by cars or tractors, children flying, children being chased by monsters, children being suffocated by giant trash cans. The children seem very much like victims, all lying back, but it was a whole new take on childhood and really upset people in the 1970s, more than my male nudes ever did.

Jack Fritscher: Is our pace all right with you? We’ve been chatting for an hour. I don’t want to tire you. We’ll finish soon.

Arthur Tress: I’m okay. I have a new glass of water.

Jack Fritscher: Please go ahead with the children again in 1970, and The Family of Man.

Arthur Tress: So I picture the children flying against the sky [“Flying Dream,” Queens, New York, 1971]. A Heaven-Hell kind of thing, dream-like states-of-being which verge on the ecstatic and the sexual as well as the Jewish racial memory of the pogrom, of the war. Many of them I photographed at Coney Island or in the slums of the Bronx. I never thought of them as erotic imagery. The pictures were making a social comment, partly on the archetypes of dreams, but also maybe on the state of children in the city. The pictures exist on both levels.

I’ve written a little bit about this, how childhood experiences never quite end. Since childhood, I’ve always felt, emotionally, when I would go to the baths or to the piers, that I was not the physical type. I didn’t have that aura of sexuality or penis size or physique that turns other men on at the piers or bathhouses. I was a bit of a wallflower. I would say to myself, my God, this is just like high school again.

Jack Fritscher: Gay life is one eternal high school.

Arthur Tress: In my work, I think there is a certain amount of the angry nerd getting his revenge on the cool guys who back in the 1950s and 1960s were not thinking about relationships. It was not on the table for discussion. Back then, I really wanted to have a boy friend, or at least have sex, whatever, but it rarely happened. So I think there is a little bit of angry revenge in those pictures, you know, like the Nerd’s Revenge. Sissy Spacek getting revenge at her high-school prom in Carrie [1976].

Jack Fritscher: The prom queen’s got a gun…and it’s a camera.

Arthur Tress: The element of revenge in that movie is an element in my photographs which gives them an edge. I know it. But don’t want to admit it. Part of my motivation in shooting those pictures was a male thing. I wanted to show I was “one of the boys.”

Jack Fritscher: That’s one of the main goals of masculine-identified gay guys. Of homomasculinity. Driven from gyms in high school, we join gay gyms to prove we’re one of the boys. A photographer is a kind of voyeur.

Gay voyeurism is a factor of the closet where you can’t be seen and all you can do is look. Boys who want to play must watch boys who won’t let them play. Like spies, we pick up our cameras like guns and we shoot them, objectify them for the divine revenge of masturbating to their captured images.

Arthur Tress: Yes. And I did gain acceptance from some men and in the art world although not from Mapplethorpe [1946-1989] or from Wagstaff [1921-1987]. They would never acknowledge my existence.

Jack Fritscher: Don’t take those two Manhattan islanders personally. As much as I liked Sam and loved Robert, and as nice as they both were to me, they did rub some people the wrong way. You were competition.

Arthur Tress: I like to think that Wagstaff knew I was as good or as tough as his little Mapplethorpe boy. But he never bought one of my photographs or anything. That caused me to have a certain feeling of alienation even while I had a desire to be part of that Mapplethorpe group, to get that cachet, to be one of those boys, to be able to say: “I can do all this just as good or better than you, Mapplethorpe.”

Even if we’re talking shooting S&M. I’ve seen some of Mapplethorpe’s unpublished S&M pictures. There is a Chinese man who has a collection of his work that included a lot of his unpublished male nudes, fist fucking with a lot of blood, penises all pinched and tied up and nailed down. I never did that. I was rarely that literal. My pictures actually have a more metaphorical poetic quality. They are, perhaps, a little bit more interesting. So there was that Mapplethorpe competition I worked around [as in the very literal picture with the title pun, “Vice Grip,” 1980, a close shot of the torso of a naked man squashing his hard penis in a giant metal vise grip].

I was, however, accepted by gay magazines. That started one summer when I had very little money and my friend Perry Brass [born 1947, author of The Manly Pursuit of Desire and Love, and founder of Gay Men’s Health Project Clinic, New York, 1972] who used to write for Mandate magazine took me down to the publisher [George Mavety] and he said, “Do some more,” and I was able to sell them for $50 each.

Jack Fritscher: As a note of comparative value of the going rate in the 1970s, that was the same amount we offered Tom of Finland for one of his drawings to appear on the cover of Drummer.

Arthur Tress: My rent was only $200 in those days. In the 1980s, many more gay magazines appeared. So if I could sell four or five pictures a month.

Jack Fritscher: A great cross-marketing scheme for you and for the magazines. At Drummer [with 42,000 copies published monthly], we launched hundreds of photographers, artists, and writers. What were some of the first pictures you sold to the gay press?

Arthur Tress: There were two male nudes: the “Hermaphrodite” [“Hermaphrodite behind Venus and Mercury,” East Hampton, 1973, from Tress’s Theater of the Mind Series] and “Man with Sheep” [San Francisco, 1974] which kind of grew out of my Dream Collector series, etc., etc.

Jack Fritscher: Which magazines did you sell to?

Arthur Tress: Honcho, Drummer, Christopher Street, Mandate.

Arthur Tress: a partial magazine bibliography: Honcho: April, 1978; June 1978; January 1979; July, 1980; April 1981; April, 1983; Drummer: June 1979; Christopher Street: April 1979; Mandate: January 1978; July 1980; August 1980; January 1981; May 1981; January 1983; May 1994; June 1984. Arthur was also listed on the Mandate masthead as a ‘Contributing Photographer” with a dozen other erotic photographers. Drummer did not pay Tress because his gallery sent his photos in trade, as did Mapplethorpe, to cash in on the international publicity of our big monthly press run.

Arthur Tress: And a couple of other magazines that have changed their names or gone under. Just a couple of years ago, I sold a portfolio to Honcho [June 1996].

Jack Fritscher: To Doug McClemont? He’s a pal and a great editor.

Arthur Tress: Yes, but it’s still the same [straight] owner in the office, George Mavety, a little guy with a big cigar.

Jack Fritscher: George is a nice guy whose Mavety Media Group publishes dozens of magazines. I’ve written many articles and stories, straight and gay, for him since the late 1970s.

Arthur Tress: So I was becoming part of that [magazine] culture which I had never really been aware of.

Jack Fritscher: Gay magazine publishing, you mean? It was slow to develop. It was my playing field. When the Supreme Court ruled [1962] frontal nudity could be sent legally through the U.S. mail, it opened the door for gay photo magazines like Tomorrow’s Man and Blueboy and Drummer to be sold by mail-order subscription across the country.

Arthur Tress: Yes. Then I had some portfolios about “Loving Couples” in Christopher Street magazine [Christopher Street, volume 3, number 9, April 1979].

Jack Fritscher: Because you mentioned in your pictures there is often S&M behind the hidden psychological agenda in our daily lives, I thought you’d be perfect for Drummer. So on March 17, 1979, I wrote to your New York gallery [Robert Samuel in which Mapplethorpe was a secret and driving silent partner] for prints and permission, and published four of the eight photos Sam Hardison sent [March 29]. To great acclaim, I must say.

The four photographs in Drummer 30 were: “Boot Fantasy,” New York, 1979, a naked man kneeling in ruins with his submissive head bowed into a bucket and a dominant leather boot on his horizontal back; “Blue Collar Fantasy,” New York, 1970, a Black man turning the wheel of an industrial machine which adds race presentation to its source influence, Lewis Hine”s “Power House Mechanic Working on a Steam Pump,” 1919, that also influenced Herb Ritts’ “Fred with Tires,” Hollywood, 1984; “Sebastiane,” a brutalized and smudged naked man tied up, hands over head like Derek Jarman’s signature movie poster for his 1976 film Sebastiane, standing in a divine swoon among the burned out ruins on the New York piers; and “Electrocution Fantasy,” New York, 1977, a naked man, gagged and blindfolded, tied into a chair in front of a ruined industrial electrical panel wired to a clock counting down to execution, knees spread revealing the vulnerable penis.

Jack Fritscher: Subscribers liked discovering the sex vibe in your work. They tore out your photos and hung them like sexy pin-ups on the wall. Your pictures have a certain sexual frisson not found in Mapplethorpe’s pictures. Your work seems reflective of the actual leather lifestyle of ritual and kink. Some critics say your pictures parody gay masculinity with camp. I think your photos document the homomasculinity lived by a majority of gay men, especially leathermen.

Drummer was a homomasculine gender-identity magazine of magical thinking. The imaginative fiction in Tress’s photos matched the imaginative fiction we published. His magical realism matched the magical thinking of the readers’ masturbation fantasies. His gothic dramatic stagings matched their role-playing as well as their gothic fantasy narratives of power and submission in homomasculine culture. My goal was to promote him as I did Mapplethorpe.

I published “Men Under Stress, Meditations on Arthur Tress: Male Apocalypse Now” in Drummer 30, June 1979, our fourth-anniversary issue for which I shot the ambiguous cover which looked like an arm-wrestling photo that the readers understood as a coded fisting photo. I opened the introduction to my “Four Meditation Poems” on Tress with two short editorial paragraphs meant to sell the pictures:

“Manhattan. One Arthur Tress photograph is worth a thousand words; but meditations on Tress, like “Meditations on the Way of the Cross” expose access to the secret world of masculinity at once dominant and submissive, esthetic and sexual, urban and urbane.

“Tress’s recent exhibition at New York’s Robert Samuel Gallery hung as an insight into the night-time fantasy of ‘Male Apocalypse Now.’ Tress is a man of distinction, a real big splendor, good to look at when so inclined. Eight hundred dollars: the complete Tress Portfolio. Robert Samuel Gallery, 795 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.”

Arthur Tress: Those gay magazines with thousands of readers helped my work be seen. Have I said enough? Is this interesting? I don’t know. Keep asking me some questions.

Jack Fritscher: Thank you. You are very interesting. How did you manage to shoot your Ramble photographs back then, out in public, when gay men out cruising did not like cameras?

From its opening in 1859, the woodsy Ramble in Central Park with its bushes and winding paths has been a gay cruising ground, fun by day, dangerous by night. The term “The Ramble(s)” became gay code for public sex by ramblin’ men. The park’s designer, Frederick Law Olmsted, chose the title-word ramble as in rambling because it means wandering…or cruising.

Arthur Tress: I’m glad you brought that up. That’s an interesting series. That was 1964-1965. I lived at 72nd and Riverside. That had two interesting aspects. One was that at that location, the Railroad YMCA and the piers were right there. I didn’t take too many pictures on the downtown piers, because we had piers and docks at 72nd street. There was a pier where males would nude sunbathe. I would go there and find models and then take them into the abandoned Railroad YMCA where I would also have props like abandoned vacuum cleaners. I had 200 rooms all with river views.

Jack Fritscher: That’s like having your own private backlot at MGM.

Arthur Tress: Yes, it was a fabulous location…like shooting the Rambles series [in the 1960s] within the Ramble.

This early alfresco work is published in Arthur Tress: Rambles, Dreams, and Shadows, edited by James A. Ganz, Getty Publications, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2023.

Jack Fritscher: Like David Hemmings photographing in a park in Blow-Up.

Antonioni’s Blow-Up features stills of the cinematic murder in London’s Maryon park by Don McCullin (b. 1935, a straight British war-baby photojournalist who began by shooting bombed-out ruins), and production stills by Arthur Evans (1908-1994). Released in 1966 when Tress was twenty-six, it is a cult film based on Swinging Sixties photographer David Bailey, husband of Catherine Deneuve. Blow-Up became an immediate classic prized among inaternational photographers for the esthetic psychology behind its then innovative concept that the artificial-intelligence eye of the camera sees more than the human eye.

Arthur Tress: At that time before Stonewall, people didn’t want to have their pictures taken so much, but I would go up to guys and photograph them. I didn’t send you too many of the images from that. People then were very almost paranoid and certainly very furtive.

Jack Fritscher: But that adds a candid paparazzi insight into the way we lived in the closet before Stonewall. You began as a street photographer [with his “Gay Activists at First Gay Pride Parade,” Christopher Street, New York, 1970]. You capture the open faces we had to keep masked before gay liberation. Your anthropological dive into and out of the Ramble turned risk into revelation. Your pictures made us visible.

Arthur Tress: Yes. But for those there are no model releases. Even so, some of them could be published. I published one in the Stemmle Monograph which I’ll send you. I titled it “Boy in Central Park” [1965] because I couldn’t then call it “Boy in the Rambles” or “Men Cruising.” [It is now titled “Boy in the Rambles.”] I had to code the title. I had to let people draw their own conclusions. A picture may be worth a thousand words, but sometimes it’s really what you title a photograph that makes all the difference. Anyway, I think I was, even at that early date [four years before the Stonewall Rebellion in 1969], trying to deal with gay imagery, homosexual imagery.

Jack Fritscher: You were a pioneer, a gay ethnographer living and working inside the scene, documenting the gay sexual underground a decade before Stonewall, before Mapplethorpe, before Peter Hujar and Marcus Leatherdale.