by Jack Fritscher

How to Quote from this Material

Copyright Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. & Mark Hemry - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

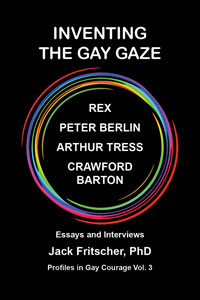

A Memoir of Essays and Interviews

Profiles in Gay Courage Vol 3

CRAWFORD BARTON

(June 2, 1943 - June 12, 1993)

San Francisco Photographer

of Beautiful Men

In Conversation with Jack Fritscher

October 2, 1990

“You can see anything

by looking out your front door in San Francisco.”

— Crawford Barton

Crawford Barton: Is this the Fritscher dude?

Jack Fritscher: Is this the Barton dude?

Crawford Barton: How are you? I’m scorching over here sitting around in my underwear. What’s happened to the weather in San Francisco?

Jack Fritscher: I’m nice and cool up here north of the Golden Gate Bridge. Are you having a good weekend?

Crawford Barton: I should have gone ahead and talked with you yesterday instead of going into the dark room. It was one of those days when I couldn’t get anything to go right and I got really frustrated. I get funny right before the full moon sometimes. I really felt it yesterday and last night. Yesterday morning I thought everything was okay, but I had a lot of trouble getting out of the house. Because I haven’t had my own dark room in years, I belong to the Harvey Milk facility. Everyone I met wanted to yakety-yak. Rink [as Rink Foto since 1960, documentary photographer of art, social, and political events] was there.

Jack Fritscher: I haven’t talked to Rink in about a week. He’s such a man about town. He’s always full of news and dish when he calls on the phone. He sent some really interesting photos he shot of Robert and me together at the Lawson-DeCelle gallery that he hopes to sell to the publisher of the Mapplethorpe book I’m writing.

Crawford Barton: Are you going to tape this?

Jack Fritscher: Yes. If that’s okay?

Crawford Barton: Yes. Do you send copies to the interviewee?

Jack Fritscher: I always do.

Crawford Barton: Do you want this to be totally spontaneous, and done now? If I think of something later, should I send you a note?

Jack Fritscher: We can talk again whenever and add what you wish. Be spontaneous. I have a few questions.

Crawford Barton: I have a sinus allergy condition and you’ll have to put up with me clearing my throat and coughing.

Jack Fritscher: Everyone I’ve talked to in California this week has been on antihistamines. Would you like to begin? Or would you like me to ask you a leading question?

[The photo book, Days of Hope: Crawford Barton Photos, edited by Mark Thompson, was published posthumously in 1994 by Editions Aubrey Walter, London, and, as a portal to the past, constitutes a collector’s gallery guide and reference survey of his work. Where possible in this interview, Barton’s photos presenting gay men’s bodies are listed by title and page number in Days of Hope: DOH. To clarify many of his photos which are untitled, descriptive “titles” have been added to aid the reader searching the internet. For instance, his 1977 Castro Street Scene series having few individual titles often appears as individual frames titled Castro Street Scene minus subtitle or specific description like Castro Street Scene, Two Couples (a kiss on the steps), 1977.

Barton captured the evolution of the gay male look from 1960s long-haired hippie to 1970s crewcut Castro clone. In his 1976 book Beautiful Men, his come-and-get-it homomasculine photo of a shirtless, hairy chested, bearded, curly-headed hunk standing hands on hips beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, backed by a high-breaking wave, references gay icon Kim Novak standing below the Bridge in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo.

It has all the jazz and jizz of a gay Tourist Bureau poster celebrating the City. To the gay gaze and the queer eye, it shows how orgasmic it felt, explosive as a foamy climax, to make a big splash and dive into the freedom of the Gay Mecca of San Francisco in the 1970s when we were escaping laws that prevented us from giving consent to our own bodies. Its frothiness is in the manner of Mapplethorpe’s phallic Gun Blast, 1985, a virtual cum shot that sprays the blast like sperm shot from a pistol — as well as of Arthur Tress’s carbonated camp in Just Call Me Squirt, 1998. I seem to remember Barton’s Splash model as a guy named “David” on Castro. A working title: David, Arms Akimbo, Golden Gate Bridge Splash, 1975.]

Crawford Barton: I can begin. You’re interested in the basic way Robert Mapplethorpe affected me?

Jack Fritscher: You, your career, your opinions about him. While your memories are fresh. Next week, he’ll be gone seventeen months. The good, the bad, the indifferent.

[“Crawford Barton was famous for documenting the blooming of the openly gay culture in San Francisco from the late 1960s into the 1980s. By the early 1970s, he was an established photographer of the ‘golden age of gay awakening’ in San Francisco. He said, ‘I tried to serve as a chronicler, as a watcher of beautiful people, to feed back an image of a positive, likable lifestyle, to offer pleasure as well as pride.’ He was as much a participant as a chronicler of this extraordinary time and place.” — Elisa Rolle, “Crawford Barton and Larry Lara,” Days of Love: Celebrating LGBT History One Story at a Time]

Crawford Barton: As I told you the other day when we were visiting, I was jealous of Robert. I was envious. He sometimes made me angry. Basically, I thought I was better than he was. He was getting rich and famous and I wasn’t. Is this okay?

Jack Fritscher: Yes, because you are saying what so many other gay photographers are saying.

Crawford Barton: I must clarify I haven’t seen every picture he did, but some of the work I have seen is truly memorable. Some of the photos are terribly important around racism, rough sex, sexual liberation. He was lucky he found his rich patron [Sam Wagstaff]. For years, I’ve tried to find a representative or manager or a secretary or a gallery that would get behind me. With all the support he got, Robert went zooming along. That made me mad. I thought in fair play I deserved it too. I also didn’t like him perpetuating dark and negative images about homosexuals.

Jack Fritscher: How so?

Crawford Barton: I was struggling here in San Francisco. I started my business as Arts Unlimited [1973-1978]. I felt like I was working my ass off as hard as he was in New York. I was shooting for publication [in The Advocate, the Bay Area Reporter, the San Francisco Sentinel, and the Los Angeles Times]. I was trying to create some beautiful, memorable, positive stuff about gay men, and here he is taking pictures of people drinking piss and mutilating their genitals. That is just too much — and I refuse to do that. I thought the leathersex pictures were kind of tacky and made to get attention. I will admit he was technically proficient; but, face it, anyone can take a bunch of tulips and make a pretty picture.

I don’t think it takes a “perfect moment” to do that. I do think that The Perfect Moment [portraits, figure studies, flowers, leathersex] was a wonderful title for that show. I ended up going to see it three or four times [at the University Art Museum, University of California, Berkeley, January 17 - March 18, 1990]. I was planning not to. I didn’t want to give him the credit, but people kept calling me up, especially black friends, saying. “Would you please go to this show and explain it to me and help me?”

Jack Fritscher: Black friends wanted a white photographer to explain a white photographer’s work about black men?

Crawford Barton: Well, they were curious with doubts, and they thought maybe if Crawford goes with us, we’ll get some insight. I don’t mean everybody that asked me to go was black, but a few were. Their curiosity roused mine so I went to the exhibit I was planning not to attend.

Jack Fritscher: How did you explain Robert to your black friends?

Crawford Barton: [Laughs] They ended up explaining it to me. I don’t remember anything precisely other than that they were fascinated that he was so interested in blacks — and I think that is one of his strong points of appeal because some of the pictures were quite ordinary, technically very nice, and relatable.

You know the one with the man sitting on the stool in four different positions? [Ajitto, 1981; see also, Phillip Prioleau, NYC (on pedestal, side facing) 1979] I just don’t think that took any imagination at all. On the other hand, the one with the guy in the business suit with his cock out [Man in Polyester Suit, 1980] is, I think, kind of neat. There’s a couple more like the two guys with torsos and legs in the same position.

Jack Fritscher: Why did you think Man in Polyester Suit was “neat”?

Crawford Barton: I think it’s a classic statement. It’s perfect and provocative. At the Berkeley exhibit, I heard the stories [instant urban legends] of people looking at the photos in the museum. A friend said when he was there, there were two little old white-haired ladies and there was a giant black guard standing in uniform near the picture, and they would look at it and look at him, look at it and look at him, and kind of like shiver. That’s interesting. A lot of things he shot, I did earlier, but I didn’t do S&M. For instance, in the de Young in 1974, I had a picture of my lover pissing. [Larry Lara, Buena Vista Park, San Francisco, page 13, DOH.] It caused quite a stir. People were dragging their children away from the wall. I enjoyed standing there and watching reactions.

[In 1974, the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum in Golden Gate Park featured Barton’s prints in an exhibit called New Photography, San Francisco and the Bay Area. His photo-book, Beautiful Men, with a cowboy-hat cover photo that rivals Jim French’s homomasculine esthetic at Colt Studio, was published in 1976 by Liberation Publications at The Advocate with a second edition in 1978. His pictures, published in the Time-Life series, Photography 1976, also illustrated the book Look Back in Joy (1990) by Malcom Boyd, the famous beatnik Episcopal priest and author of the 1960s bestseller Are You Running With Me, Jesus? Boyd was the longtime husband of The Advocate editor Mark Thompson, my longtime friend, who collected the photos and wrote the foreword to Crawford Barton: Days of Hope: 70s Gay San Francisco published posthumously in 1994 in London by Editions Aubrey Walter which also published photo books by Arthur Tress, George Dureau, Chris Nelson, Jack Fritscher, and others.

For two decades, gay faerie Mark Thompson, the author of Gay Spirit: Myth and Meaning was senior editor at The Advocate, and, along with influencer Boyd, a constant champion of Barton’s work. Thompson hired Barton to help support him as a staff photographer, but Thompson and Boyd were minor-league patrons compared to Mapplethorpe’s Sam Wagstaff with his old money and his New York and European connections. In the 1980s, Barton wrote his epic novel of the golden age of gay awakening, Castro Street, and a book of poetry, One More Sweet Smile. Both unpublished.

His photo, Harvey Milk, 18th & Castro Street, San Francisco, 1973, page 37, DOH, is in the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, a gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art and of Edward Brooks DeCelle. His street photo, Harvey Milk Campaigning on Castro Street, Summer, 1973, is part of the permanent Crawford Barton archival collection at the San Francisco GLBT Historical Society.

Barton’s most iconic queer pop-culture picture, Castro Street Scene, Two Couples (a kiss on the steps) 1977, depicts his staged scene of two juxtaposed couples. One couple is bourgeois with a straight man in a suit sitting on the steps with a woman in a light-colored dress, knees closed, clutching a big purse, both staring off in the direction of the nearby intersection of 18th and Castro, looking away from the gay couple — while in another frame the exact same straight couple look into each other’s faces. The other seated couple engaging in a kiss, knees open, are Castro clones, gay and bearded and perfect in white T-shirts. Barton’s quartet says everything about the working-class Irish couples with families who lived in the Castro, sold their homes to gay couples arriving with money, and came back to their old neighborhood to see how their Eureka Valley had become The Castro.

The photo was shot in black-and-white on the famous Rainbow Steps of the gay bookstore Paperback Traffic at 558 Castro Street. That afternoon at that location, Barton directed and shot several alternative frames, some with blue-jean legs behind the two couples, some without, as well as other frames of two different couples straight and gay with the gay one kissing. (Page 36, DOH.) Like the iconic Gone with the Wind poster of Rhett kissing Scarlett, this instantly recognizable “postcard” photo has taken on an emblematic life of its own as a poster for the Castro gayborhood before it became a war zone of AIDS. As a signature totem of nostalgia, Two Couples has appeared in several films: Gay USA, 1977; The Butch Factor, 2009; We Were Here, 2011. In 1994, I published it as a totem in Mappletthorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera.]

Jack Fritscher: So you think Robert’s leather pictures exploit gay men? That his S&M pictures are a bad press release for homosexuality? Would you rather he show gays in suits and ties and loafers like The Advocate [under publisher David Goodstein] advises us to be in its pages so people accept us?

Crawford Barton: Healthy looking pictures of gays? Yes. Guys in loafers, T-shirts and jeans, And Castro clones, I guess. I’m basically a documentary photographer, and I do portraits too, but my work is positive and, well, California, not New York.

Jack Fritscher: In the early 1970s, Robert, like you, went outside to shoot healthy beautiful men lolling poolside in the Fire Island Pines. [Scott Bromley, 1972; Peter Berlin, 1977; Tattered American Flag, 1977]

Crawford Barton: I always thought all his work had an unwholesome feeling. Even his still-lifes of flowers were shot indoors, never outside in a garden. I think he once said, “Oh, my flowers are New York flowers.”

Jack Fritscher: His studio was his hothouse. He and Patti who did his reading for him were always comparing whatever they did to Baudelaire and Rimbeau. Like working for extra credit after school. They grafted his night-blooming New York flowers on to Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil.

Crawford Barton: He shot everything behind closed doors. After growing up in a closet in Georgia, I like to get out of the studio, out of the closet, and into the streets.

[Barton’s street photography in which one picture can illustrate a thousand words also invites the kind of literary comparisons promoted by Patti Smith. His street fair and parade photography contains multitudes like Walt’s Leaves of Grass. For instance, in Two Shirtless Men Embracing, Gay Freedom Day, San Francisco, 1977, two men standing in a huge crowd embrace one another like Whitman’s Calamus lovers in his tender poem, “What Think You I Take My Pen in Hand to Record?”: I “… record of two simple men I saw to-day, on the pier, in the midst of the crowd, parting the parting of dear friends; The one to remain hung on the other’s neck, and passionately kiss’d him, While the one to depart, tightly prest the one to remain in his arms.”

In his candid alfresco series After the Parade, Lafayette Park, he documents crowds of clothed and nude gay men cavorting and dancing in what Whitman celebrated as “He-festivals” in Song of Myself in which he applauded “He-festivals, with blackguard gibes, ironical license, bull-dances, drinking, laughter.” Pages 42 to 45, DOH.

In his staged photo of three men (two shirtless in button fly jeans with top buttons undone in readiness as was the custom) standing around a fourth man seated in his MG sports convertible double-parked in the middle of Castro Street, Barton again channels Whitman. The picture might be descriptively titled, Castro Street Scene, Four Men and an MG Double-parked in Front of the Castro Theater. He pictures his lead actor, Larry Lara, the black hole of his mouth agape, teeth bared, shouting, yawping the yawp of Whitman’s “Barbaric Yawp” of male autonomy, joy, and radical freedom on location in front of the towering blade sign of the Castro Theater. The exact line from the poem is “I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.” Barton’s pictures could illustrate Whitman’s poetry in Leaves of Grass the way Mapplethorpe’s pictures illustrated Rimbaud’s poetry in Arthur Rimbaud and Robert Mapplethorpe, A Season in Hell, New York: Limited Edition’s Club, 1986. Edition: 1000]

Crawford Barton: Robert’s still-lifes have such a claustrophobic feeling.

Jack Fritscher: Cut flowers are dying flowers, dead flowers.

Crawford Barton: The flowers, especially the ones in color, are so uniquely sharp and clear that there’s nothing unusual about them. Mechanical. No interpretation. He wanted to focus on a tulip and take a perfectly rendered picture of it.

Jack Fritscher: More literal than metaphorical? It’s not faint praise to say some look like beautiful commercial photographs he could have sold to Kodak to advertise its newest film stock.

Crawford Barton: I just feel like flowers are pretty. So it’s easy to take a pretty picture. Flowers are the sex organs of plants. I think that’s why he liked them.

Jack Fritscher: That’s one reason he liked them. He could show sex and beauty in flowers where people didn’t mind the combination. Pop culture is mass culture. It thrives on the public curiosity to see what’s behind the green door. Everyone wants to see inside everything.

Crawford Barton: I think that’s why The Perfect Moment was so popular. People could not resist…

Jack Fritscher: …his Traveling Peep Show?

Crawford Barton: …because they wanted to see something naughty that they could see nowhere else. They got off on being a little bit bad by going to a museum and not some carnival to see the freak show.

Jack Fritscher: So, after Stonewall, it was a way for straight people, gay friendly or not, to check out gay things they’d only starting to hear about.

Crawford Barton: I think he could have been more educational, less sensational. I haven’t thought a lot about it, but he could have made his work less gruesome. I have a problem with S&M. I don’t understand it. I don’t understand why anyone would want to do it and I don’t understand why someone would necessarily take pictures of it.

Jack Fritscher: Maybe because like Mount Everest, it’s there and hasn’t been shot before. When you see paintings of torture like the Passion of the Christ, Saint Sebastian, Saint Peter, or even The Flaying of the Satyr Marsyus [Robert’s X-Portfolio picture, Dominick and Elliot], do they suggest that Robert is creating inside a religious esthetic of suffering endured by willing victims like Christ or Sebastian? Robert was first and last a Catholic.

Crawford Barton: I don’t know about religious overtones because I’m not a religious person. I don’t understand religion either. It’s just violence.

Jack Fritscher: Yet, the people who are looking at his pictures and having the worst response to it are the most “religious.”

Crawford Barton: That’s true.

Jack Fritscher: Did he bait them to make news and sell pictures? He takes religious art and spins it around gay sex and his subversion drives them mad. Fundamentalists hate art because they are literal about the Bible and don’t like the ambiguity of art.

[The Protestant Reformation, suspicious of art and metaphor, led to today’s fundamentalist censorship of art. When Protestant reformers destroyed monasteries and stole Catholic church buildings, they white-washed the walls, paintings, sculpture and ornamentation to erase centuries of idolatrous “Roman” art because its metaphorical ambiguity was contrary to their literal reading of the Bible and the Second Commandment that forbids making graven images. Scholars estimate that in the 16th century, militant iconoclasts destroyed 97% of the Catholic art in England. The Puritans brought this critical gaze to Plymouth Rock and installed its anti-art fundamentalism in American consciousness and politics, especially in the South where Barton was raised.]

Crawford Barton: I grew up learning all the problems about sexually unliberated church people. They can’t stand seeing other people having some degree of total freedom. They draw the line at sex. The 1970s were the most sexually liberated period in U.S. history and maybe the world.

Jack Fritscher: Maybe the Cosmos. Rome. The Weimar Republic. The Meatpacking District. Castro Street.

Crawford Barton: So it’s not surprising he did it when he did.

Jack Fritscher: He was a man of his times. He lived his life and shot what he knew. So how is he different from the hundreds of photographers who shot for all the gay magazines like Blueboy, Honcho, Christopher Street, and Drummer? What makes Robert’s pictures fine art?

Crawford Barton: Aside from the fact that he’s technically very good like Ansel Adams, he pushed and shoved to get into galleries and museums, and the people in Drummer did not. You could say he had the balls.

Jack Fritscher: He had career balls to get institutional endorsement.

Crawford Barton: He could stand there and say to people. “I’m an artist, I’m a serious artist.”

Jack Fritscher: If they balked, he had a great sales pitch: “If you don’t like this picture, maybe you’re not as avant-garde as you think.” If you repeat something often enough and get other people saying these things in your social circuit…

Crawford Barton: You get shows everywhere and sell your prints for lots of money. The only thing today is to “be” an artist and stick with that. Don’t sell out. That doesn’t mean what you produce is going to be a masterpiece and be remembered ten years later, but it means you’re honest. Robert may have been honest, but he wasn’t honest enough.

Jack Fritscher: Is there anything in Robert’s work that you think will be remembered in the history of photography?

Crawford Barton: Most of it is technically good and pretty to look at. I think his attitude, his new thinking of photography as a fine art, which he learned from Wagstaff, is more important than his work. Robert was a liberating teacher in the art world.

Jack Fritscher: He and Sam kept repeating “Photography is a fine art” until the art world finally believed them and sent prices skyrocketing. Do you think that Robert was at all political, or did he pursue his own career and get political by accident when the world turned on him?

[The essential Robert Mapplethorpe, who became an icon of the Culture Wars, favored pure static form over the fray of politics, but around issues of race, sex, gender and identities, one could consider that Robert’s coverage of disenfranchised gay men, women, and blacks was start-to-finish a slow-burn political mission of visibility that grew in subversive intensity. The jurors at the Cincinnati obscenity trial decided his work was “artistic and politically important, no matter how disturbing the homoerotic images might be.” After the manner of Dan Nicoletta’s photo of Harvey Milk on a U. S. postage stamp in 2014, Robert’s Ken Moody and Robert Sherman, 1984, is a virtual U. S. postage stamp of race relations.

In 1981, Robert shot a devastating political portrait of Donald Trump’s then attorney, Roy Cohn (1927-1986), the loathsome gay lawyer who was infamous for his part in Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy’s House Un-American Committee that did so much damage to the country, to gay people, and to the arts in America in the 1950s. The eerie photo of Cohn’s disembodied head floating in a black void and titled Roy Cohn, now in the National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian, might have been better titled Bring Me the Head of Roy Cohn.

In 1989, thirty-seven days before Robert died, he shot United States Surgeon General C. Everett Coop who led the national fight on AIDS during the presidency of George H. W. Bush after Republican President Ronald Reagan who could not even speak the word AIDS. Time magazine published Robert’s portrait of Coop on the cover of its April 24, 1989 issue. It was Robert’s last commissioned portrait. On May 27, 1988, ten months before he died, Robert founded the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to promote photography as fine art and to support HIV/AIDS medical research.]

Crawford Barton: I didn’t know him that well. I feel like saying he got political by accident.

Jack Fritscher: The big controversy about him didn’t begin until a hundred days after he died. He got no joy from it. He never knew how famous he’d become.

Crawford Barton: I never really sat down and had a long conversation with him about his opinions.

Jack Fritscher: When you look at his photographs, do you see political content? Declarations of sexual independence?

Crawford Barton: Unlike others, I always thought of sexual freedom as non-political. I think it’s everyone’s right. Maybe he set out to explore his sexual fantasies and got politicized in the process. Politics is another thing that baffles me like religion. It works for people who know how to manipulate it. I think Robert knew very well how to manipulate people the way he manipulated his camera and his models. Did he try to manipulate you?

Jack Fritscher: I could make a sex joke here. But, no, he didn’t. We collaborated [on Drummer work and a potential book] without manipulation. He was good at manipulating himself in his self portraits where he’d do things like sticking a whip up his bum or putting on women’s makeup.

Crawford Barton: Not in the same picture, thank God.

Jack Fritscher: Do you think with his S&M pictures and his role-playing auto-shots that he was trying to reach people or outrage them? Outrage is a political term. With Larry Kramer and Act Up, it’s a virtue. Does outrage win people over? Outrage is a maneuver The Advocate doesn’t like.

Crawford Barton: The way I would explain outrage if I had to is that, for instance, drag queens pave the road for ordinary gays to come out. Drag is not as shocking now as in the early days, but still, drag queens and S&M are the outrageous extremes. They may help some people come out, but most homosexuals are not like either one. To tell the truth, I’ve been in the gay community of San Francisco for so long that I don’t know what’s outrageous anymore. Is Mapplethorpe outrageous in our outrageous culture? Can anyone be? We’ve seen and done things in the 1970s that would shock ordinary American Nazis. That’s where Mapplethorpe crossed the line. Maybe he was trying to educate people. But you have to do it gradually. You can’t suddenly stick a bloody penis in front of their faces and expect them to accept it.

Jack Fritscher: And yet people applaud circumcision.

Crawford Barton: They think of that as a necessary religious and health experience. I’m a very sensitive person. I see a finger get cut and I have to turn away.

Jack Fritscher: What do you think of his presentation of women?

Crawford Barton: I think it’s basically positive — although I think he portrays women as a gay man would do it. He chose muscular women, lesbians, or outrageous women. The women got off easy compared to how he sexualized men.

[Barton’s undated photo, Donna and Friend, San Francisco, and Toby and Family (two lesbian mothers with their child), pages 9 and 67, DOH, are very like Richard Avedon in his photo book, In the American West, 1979-1984. In 1975, Barton documented Jo Daly, the first lesbian Police Commissioner in San Francisco.]

Crawford Barton: His men and leathermen are more sensational. He’ll be remembered for his S&M statements, then his blacks, but they will always be associated together as somehow forbidden. He probably wouldn’t have made such a big splash without the S&M, but he may have helped education around race with his more wholesome pictures of blacks. I think the black pictures are fine.

Jack Fritscher: You don’t find them stereotypical with the penises and muscles and bulging tights…and guns? [Jack Walls (holding pistol parallel to his erect penis), 1982.

Crawford Barton: I’m a documentarian. So, no, that’s just how the models looked. They’re not really exaggerated. He’s not taking them to some extreme. They are what they are: black men. They just seem extreme because of racial fear of black men. I agree with him on his black interpretation. I think he is saying blackness isn’t threatening. You just think it is because of racial problems in America.

[Robert had the good fortune of riding on what Tom Wolfe satirized in 1970 as “Radical Chic” after Leonard Bernstein invited high society to a Manhattan party he hosted for the Black Panthers so his rich friends could assuage their white guilt and feel liberal and grand, with no irony, lighting cigarettes and serving cocktails to black revolutionaries. A decade later, they were buying Mapplethorpe’s blacks as trophies of their liberalism.]

Jack Fritscher: Did your black friends who went with you to his show comment upon a white photographer presenting black males in this way? Is it documentary or stereotype when he poses a headless black model in a cheap suit with his prodigious penis hanging out, or a young nude black New Yorker draped with a cheetah skin and holding a spear? [Isaiah, 1981]

Crawford Barton: No, they mostly said, “The model has great skin.”

Jack Fritscher: Have you photographed many blacks? Castro Street where you find models is mostly white.

Crawford Barton: Not a lot. I had the same idea as Mapplethorpe about shooting black men because it was an area that had not been explored very much. There weren’t any black gay photographers then that I can think of.

[Crawford Barton’s photos representing black men include After the Parade, 1974, page 22, DOH; Jim McKell and Friend, page 54; Nude Study, page 56; Romney (black man on bus bench), page 60; and Black Man Standing Shirtless in Front of Adult Movie Theater Posters, Tenderloin, San Francisco, 1970s.]

Jack Fritscher: Perhaps you’re aware of Craig Anderson [1941-2014] who is white and for years has shot rapturous pictures of black men for his Sierra Domino Studio here in San Francisco. [Unlike Robert, Anderson rented his models to his photography clients at his studio parties.] Do you know of any other whites photographing nude black men?

Crawford Barton: I don’t know of any. You might ask Dan Nicoletta. He’s a gay photographer who’s been around a long time, He started working in Harvey Milk’s camera shop at the age of seventeen. He ended up using my studio on Church Street. He may know of some. Do you want his number? It’s 665-59….

Jack Fritscher: Thanks. He’s in my Rolodex. I know him and his work. Prolific with a great eye. What’s your bottom line about Mapplethorpe? Was he anything besides sensational?

Crawford Barton: Yes. He was technically very good. But many of his images are very ordinary. I don’t understand a lot of his work and why he did it. He created a whole series of picture frames for his photos and hung them like geometric arrangements and sculptures that I don’t understand at all. In some of his series, it’s the same subject shot from different angles forming a cross with a black center. What is that? I don’t get it.

Jack Fritscher: Robert began studying sculpture at Pratt, built installations, and designed jewelry. Before he ever picked up a camera, he made lots of mixed-media collages using other photographers’ erotic male images he found in 42nd Street adult bookstores. His repetitions are very Warhol. His crosses are Catholic. He works with religion. Like Fellini.

[Robert Mapplethorpe, Christ [photo of a crucifix] (1988), Folded Card for the Exhibition Three Catholics: Robert Mapplethorpe, Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha,” Cheim & Read Gallery, 1998.]

Crawford Barton: Well, I don’t get that. I mean arranging pictures of an erect penis in three different positions? His geometric arrangements are not new. So you think that’s a religious statement?

Jack Fritscher: As a main icon of western art, The Crucifixion plays a major part in his design and arrangement. In his Creatis catalog, which was the first gift he gave me, his cover shot is a self-portrait of just the upper quarter of his torso, and his grinning face, and his right arm stretched to the vast reaches of the frame and his palm is open waiting for the nail to be driven in. Like a young artist exposing himself to critics for his own delicious crucifixion.

[Creatis, La Photographie au Present, No. 7, 1978, was “un magazine bimestrial, vendu dans les galeries, les librairies specialisées,” printed in Paris by Albert Champeau, publisher, and Mona Rouzies, art director. Creatis was published two years after Barton’s primary reference book Beautiful Men and at the same moment Barton shut down his Arts Unlimited business.

In a tale of two cities, as the gentle Barton, a born Southerner, lived life without a catalogue raisonné in laid-back San Francisco, the prolific Northerner Mapplethorpe rose in the fast lane in New York. Crawford’s layabout muse Larry Lara was no motivational Patti Smith. Beautiful Men surveyed Barton’s past. Creatis projected Mapplethorpe’s future.

By the 1976 American Bicentennial — coinciding with Barton’s career high-point in Beautiful Men — Mapplethorpe was surrounding himself with observant writers and eyewitness photographers and the idle rich to build his brand.

Robert, the urban leatherman, was sitting front row at Paris Fashion Week rising to the full height of his powers, while Crawford, the hippie farm boy, cruised on shooting a confederacy of idle beauties in the Castro Street He-festival that was the “Golden Age of Sex” in San Francisco — that orgiastic decade of gay fraternity before the onslaught of AIDS in 1981 when Barton settled in as the local photographer of the San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus. Cities breathe. Sometimes they inhale you. Sometimes they exhale you.]

Crawford Barton: I’m not tuned into religion or S&M. I see sex in the flowers, but I don’t see religion in penises and bondage.

Jack Fritscher: Meaning like beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Some of his frames alternating three pictures in one line alongside one mirrored frame reflecting the viewer’s face are meant to suck the viewer into the picture. The seer becomes the seen. Art is what you bring to it. You needn’t see theology in his work, but it was part of Robert’s creation.

[Robert who began his career creating picture frames carefully designed a layered presentation of the gay fetish for rubber gear in Joe, 1978. He framed and mounted his photo flat on the center of a mirror placed behind a transparent pane of smoked glass whose reflective finish repeats, along with the mirror, the face — includes the face, makes an immersive montage of the face — of the viewer standing in front of the picture.]

Crawford Barton: So…what do you do with his picture of a fish laid out on some newspapers?

Jack Fritscher: Maybe it’s a comment on newspapers and publicity. On one level, it’s a sports picture of a fish. On another level, it’s a comment on the media. Fishwrap is a slang term for yellow journalism in newspapers like The National Enquirer. On another level, a deeper dive, it may be a comment on religion. The fish is an ancient symbol for Christianity.

Crawford Barton: Do you understand his fascination with socialites? Women with very pale light skin against a dark background?

Jack Fritscher: Women with wallets. Their socialite money fascinated him. He loved being the artist at their supper tables. He loved high society. Princess Margaret and all that. He took a lot of pictures of Greek and Roman female statuary which he applied to Lisa Lyon, and he gave some of his society women a classic-cool marbled look.

[Robert was genius at turning women and men to stone. He made glorious statuary of sitters like Melody Danielson, 1987; Ken Moody, 1983; Desmond, 1983; and Ken Moody and Robert Sherman, 1984. In 2014, the French paired Mapplethorpe with Rodin in the exhibit Mapplethorpe - Rodin, Museum Rodin, Paris.]

Crawford Barton: Speaking of statues, why did the Whitney chose one of his statue pictures for the cover of his exhibit [Robert Mapplethorpe, Whitney Museum of American Art, curated by Richard Marshall, 1988].

Jack Fritscher: It was a new photo he shot of the profile of a white marble statue of Apollo. [Apollo, 1988] He was dying. People were in a rush to create hooks to position him in art history.

Crawford Barton: Did he care about being a figure in history?

Jack Fritscher: Sam made him aware of history. He and Sam worked hard to convince collectors and critics and gallerists that there was a canon of historical fine-art photography that deserved respect in museums and galleries — and that Robert was a continuation of that canon. A passionate few can make a reputation.

Crawford Barton: I think I can tell what’s good art and great art. I just have a feeling about it.

Jack Fritscher: Like the Supreme Court Justice [Potter Stewart] who said he couldn’t define pornography, but he knew it when he saw it.

Crawford Barton: Yes. I have feelings about intuition, uniqueness, skill involved, beauty. There’s so much junk being produced now. There always has been.

Jack Fritscher: What do you think of Herb Ritts?

Crawford Barton: He’s another skilled technician. He’s great with faces and bodies, but I think his pictures made into all the giant posters you see everywhere are just there to titillate gay people into buying them. Basically, it’s just physical exploitation again. Just pretty bodies with carefully covered genitalia.

Jack Fritscher: Why do you think everyone gets so riled up over the penis?

Crawford Barton: Oh, lordy, lordy.

Jack Fritscher: I mean in art.

Crawford Barton: That’s a very good question.

Jack Fritscher: People accept frontal nudity in women. Europeans don’t care about frontal nudity of either sex. In America, there’s this enormous fear of the penis.

[In March, 1994, the year after Barton died, outré culture warrior Camille Paglia hosted the controversial program Priapus Unsheathed, for Rapido TV, Channel 4, London, in which she asked me to join with other talking heads to speak, as I had with Crawford, about cultural fear of the penis. Paglia included transcripts of that show in her book Vamps and Tramps: New Essays, 1994.]

Crawford Barton: I don’t know if I know the answer right off the bat. Nude females became acceptable and nude men did not. Are you talking about an erect penis or just a penis?

Jack Fritscher: Any penis.

Crawford Barton: Isn’t penis what that one man [U. S. Senator Jesse Helms, Republican, North Carolina] got so bent out of shape about because Robert showed a black penis?

Jack Fritscher: It was Man in Polyester Suit. Jesse Helms called it “filthy art.” What do you expect of a single-minded person who lacks visual literacy and whose religion is always bitching about sex? The only endowment they like is female breasts. Helms, by the way, is a Baptist.

Crawford Barton: All that religion and sex and race stuff. I had no religion growing up as a child of Baptist parents and brothers and sisters. I chose not to subscribe to all that although Jesus was my only role model. I grew up on a farm in Georgia. [My Father in His Corn Patch, Northern Georgia, 1975, page 6, DOH] I didn’t even know who the President was. Not until I was old enough to read did I realize there were gay men out there that I could pattern myself after. Maybe my early Jesus thing is why I deplore meanness and rudeness and aggression. I’m kind of Jesusy.

Jack Fritscher: Jesus took a whip and drove the money changers from the temple.

Crawford Barton: But I doubt if he drew blood. I think Robert produced several memorable images, certainly the whip picture [Self-Portrait with Whip, 1978].

Jack Fritscher: What do you think that’s about?

Crawford Barton: I think he was saying: This is my body. This is my asshole.

Jack Fritscher: That’s very close to the words of Consecration in the Catholic Mass. “This is my body. This is my blood.” Robert lived that mantra.

Crawford Barton: Really? I think he’s saying I’ll do whatever I please with my body, and I’m going to make you aware of that. The fact that he is doing it with a leather whip and not a banana keeps it serious.

Jack Fritscher: Cool you mention that. Do you remember Warhol’s silkscreen Banana on an album cover for the Velvet Underground? [The Velvet Underground & Nico, 1967] Referencing Andy, Robert did in fact shoot a campy banana with a leather strap wrapped around it with keys dangling from the strap [Banana with Keys, 1973]. But regarding the whip does that seem at all scatological to you?

Crawford Barton: Not particularly.

Jack Fritscher: Maybe this campy picture is about pulling art out of your ass. Maybe it’s about penetration, the way in, or is it about evacuation, the way out? The bullwhip’s long tail evacuates out scat-like down its full braided length, and trails out the bottom of frame.

Crawford Barton: Considering what I’ve heard about him I suppose that’s possible.

[It was the talk of the town when Robert shot his portrait of Katherine Cebrian, the elderly San Francisco grande dame, because the bright silver studs on the back of the big leather belt he wore at that time spelled out shit. Katherine Cebrian, 1980]

Jack Fritscher: That’s art interpretation for you.

Crawford Barton: Were you there for that shooting session?

Jack Fritscher: Oh, God, no. But I enjoyed his psycho-drama take on things.

Crawford Barton: At a lecture?

Jack Fritscher: No. Role-playing during the three years of his high S&M period while we were dating before he switched to black men. The whip photo is like a still frame from a motion picture going on in his head. He’s shot a couple of short films. His pictures are like still frames from a movie montage he’s slowly assembling.

[In the Chelsea Hotel in 1970, Robert appeared in the lap of his lover David Croland with Patti Smith nearby keening on the soundtrack in Sandy Daley’s film Robert Having His Nipple Pierced. In 1977, he shot Patti solo for his thirteen-minute black-and-white film Still Moving.]

Crawford Barton: That whip is very Satanic. Very sodomy. It’s many, many things.

Jack Fritscher: He wanted it to look evil, but playful, the way Pan looks evil but fun. He shot himself as Pan with two little horns sticking out of his hair [Self Portrait, 1985]. He loved playing at being Satan’s bad boy like you tried to be Jesus’s good boy. He tried holiness as an altar boy, and it didn’t suit him. He tried being a hippie in the 1960s, but all he took from the Flower Child scene were the flowers. He tried being part of the gay scene, but he disliked gay ghettos except for recruiting the men and scenes he wanted to shoot in places like the Mineshaft.

Crawford Barton: I knew he didn’t hang around the gay ghettos.

Jack Fritscher: He felt if you didn’t move out of the ghetto, you’re still closeted. Other photographers who envied him did not like that attitude.

Crawford Barton: Lucky for him, he could afford it because of Wagstaff. You know what else I think is an important image? The naked black man dancing with the white woman in a white gown. [Thomas and Dovanna, 1986] If you hung that picture, or those two guys dancing [with crowns on their heads, Two Men Dancing, 1984] on your wall in South Georgia, you’d be crucified, or the Ku Klux Klan would come burn you out.

Jack Fritscher: Fashion photography. That’s a reason to be lynched? Here you are, Crawford, a nice man who doesn’t like violence. You are an artist, and you are the child of a violent region. How do you account for your escape?

Crawford Barton: I did go around with men who are kind of like the wild mountain men in Deliverance [the 1972 box office hit in which primordial mountainmen attack a group of four civilized Atlanta businessmen — and rape one — on a weekend hunting trip in the Georgia wilderness]. Well, maybe not to that extreme, but those kind of men were there in the mountains around our farm. I was lucky I had such gentle loving parents. They went to church. They liked spiritual religious music, not classical. They had a garden. They cooked.

Jack Fritscher: So did Robert’s parents. When did you first start shooting pictures? When did you first consider yourself a photographer? Were you born with a camera in your hand?

Crawford Barton: I guess the late 1960s. I took pictures when I was a child. I didn’t just point and shoot. I composed them. Visually I was doing art, but I didn’t know it. I still have some of those negatives. I got my first 35mm camera in the late 60s. I was also a painter and I was trying to be a writer. I wanted to be a filmmaker. So learning photography was something important for me to do that I could do readily.

Jack Fritscher: You’re like Robert in that regard. He said something like “If I had been born a hundred years ago, I might have been a sculptor, but photography is a very quick way to see, to make sculpture.”

Crawford Barton: Exactly.

Jack Fritscher: I mentioned Robert was a filmmaker. What did you think of his films?

Crawford Barton: I don’t think I’ve seen any of them.

Jack Fritscher: I think he thought the same as you and Warhol that filmmaking is an extension of the still frame. Warhol moved from Polaroids to filmmaking and video portraits he called Screen Tests. Godard says “Photography is truth. The cinema is truth twenty-four times per second.”

Crawford Barton: Yes, yes. Godard! In the 60s, filmmaking was the only art form for me when I studied film at UCLA because it combined all the art forms that I could do well. I have never had the opportunity to make a feature film. I have shot Super-8 movies and some of them are almost an hour long. [Gay Parade 1978, Super-8] I’ve been meaning to transfer them to videotape, but I hate TV.

Jack Fritscher: TV isn’t video. Video is something other than TV.

Crawford Barton: You have to show videotapes on TV.

Jack Fritscher: No, you view them on a monitor.

Crawford Barton: Well, that’s about as bad. I think TV distorts. I’m such a film buff. I get real angry if someone says I should put my films on a cassette. I wouldn’t watch a videotape if you paid me.

Jack Fritscher: Actually, what we’re doing right now on the phone without seeing each other is going to be prehistoric in a few years when we’ll have videophone. Last summer when I was shooting erotic videos in West Berlin, the producer showed me a tiny still camera that doesn’t use film.

Crawford Barton: I think the making of a 35mm feature-length film is very archaic, but until they perfect the cameras and film stock, we’ll never see the whole picture the way it was intended, clear and sharp and all that.

Jack Fritscher: They have. It’s called high-definition television. In Europe, broadcast television looks glorious. It has 560 lines of resolution and we have about 250-350.

Crawford Barton: I also have a thing about watching a big picture on a big screen. I don’t like sitting on my couch staring across the room at a small 8x10 TV image on a wall. That’s what TV looks like: an 8x10. I realize all of this technology is going to work itself out.

Jack Fritscher: Maybe your next period will be as a great videographer, applying all your skills because video does make filmmaking accessible to people. That’s why Robert was able to shoot videos of Patti in the 1970s. Like Warhol, he was one of the first people to have a video camera.

Crawford Barton: Maybe videotape is the only way to reach everyone. Did you see the newspaper article a couple of weeks back on still photography done on computers?

Jack Fritscher: Yes. With computer manipulation, is still photography any longer only a document of truth? [Antonioni’s] Blow-Up [1966] was an interesting study about finding truth in a photograph.

Crawford Barton: That’s why technology bothers me being a candid photographer, a documentary photographer trying to capture what’s actually there. Like Blow-Up. My work doesn’t carry the weight it used to.

Jack Fritscher: There’s an awful lot going on with all this change, isn’t there? None of us knows what will be happening in fifty or a hundred years with your photographs.

[Twenty years later in 2013, Crawford Barton’s photographs and Super-8 movies of his gay migration from Georgia to San Francisco were edited into existing Civil War histories to create The Campaign for Atlanta: An Essay on Queer Migration at the Atlanta Cyclorama and Civil War Museum. Curators “John Q” aka Wesley Chenault, Andy Ditzler, and Joey Orr saluted the value of Barton’s queer eyewitness in his historical films and stills like his picture of his father on his farm in 1975 and his Goat Man [with his Jesus sign] Calhoun, Georgia, 1960s, to illustrate aspects of the great gay migrations of the 1970s.]

Crawford Barton: I’m too tame to be remembered, but I do think I have captured some truly beautiful moments with truly beautiful men in a truly beautiful city. It seems the world is going in a violent direction rather than a peaceful direction.

Jack Fritscher: Endism is a philosophy that has become part of popular culture. Even among gays because of AIDS. I don’t believe in it myself. Endism? Is the end really near? Not if you study history. Endism comes out of fundamentalist religion waiting for the Apocalypse which like Godot never comes.

Crawford Barton: All you have to do is go out your front door.

Jack Fritscher: Why, because it looks like the end of the world?

Crawford Barton: You can see anything by looking out your front door in San Francisco.

Jack Fritscher: What about those people back in Georgia looking out their windows? What happens when the Mapplethorpe exhibit comes to… What town were you born in?

Crawford Barton: Outside Calhoun where I went to high school. It was the nearest town. but I was born out in the sticks. But Mapplethorpe will never get there.

Jack Fritscher: AIDS got there.

Crawford Barton: Sooner or later, Mapplethorpe will be exhibited in Atlanta even though it’s probably ten years behind California.

Jack Fritscher: The Mapplethorpe controversy has already gotten there on the news. Will Jesse Helms be as remembered as Robert Mapplethorpe in ten years? There will always be another reincarnation of Jesse Helms. That fascist mentality comes along on repeat in history, and each time that it does, it seems that art and homosexuality manage to beat it and survive.

Crawford Barton: I thought censorship was disappearing.

Jack Fritscher: Really? Today? [October 2] With the Mapplethorpe obscenity trial going on right now in Cincinnati even as we speak? [September 24 - October 5, 1990]

Crawford Barton: I don’t watch TV.

Jack Fritscher: Government censorship is a bad mix of church and state. Do you think the government has the responsibility to fund art? That artists have a right to government grants?

Crawford Barton: No.

Jack Fritscher: Actually, censorship of Robert is not as much about art as it is about homophobia. When society won’t let you kill the artist, kill the art.

Crawford Barton: I don’t think Mapplethorpe should be censored anymore than I should be. If someone is into S&M, I’m sure some of his images are very pleasing. What pleases me is love, tenderness, and all that. Mapplethorpe made a leap, and he did it fast and just in time. If he did it my way, which is gradually, he wouldn’t have become a star. I have AIDS. I don’t care if you quote me. I won’t last long enough to accomplish what he did.

Jack Fritscher: He died at 42. You’re how old?

Crawford Barton: 47. And you?

Jack Fritscher: I’m 51.

Crawford Barton: AIDS?

Jack Fritscher: No.

Crawford Barton: You’re lucky.

Jack Fritscher: Yes, but driven because AIDS exists. My first lover of ten years [photographer David Sparrow (1945-1992)] has AIDS. The horror of it all. I write to keep dead friends alive. Looking inside your own internal sensibility around AIDS, do you think the fact that Robert had AIDS caused him to speed up shooting everything in sight? In his last years, he shot more than he ever shot before.

Crawford Barton: That’s probably a definite yes. Sometimes I think I’ve slowed my pace, but I’m working harder and I’m more productive than ever before, even with AIDS, maybe because of AIDS.

Jack Fritscher: Do you think speeding up your shooting has influenced your quality?

Crawford Barton: I think its gotten better. A kind of urgency has enhanced it.

Jack Fritscher: Has AIDS focused your art and life so you can capture the moment you want, your perfect moment, better in both the camera and the dark room?

Crawford Barton: AIDS has made me feel more urgent. I’m better because I’ve been shooting more, but that also comes out of my long years of experience. Without AIDS, I think I would have been doing the same quality, but not as fast. My art will last longer than I will.

Jack Fritscher: Your answer as a working artist is such an important insight because we can no longer ask Robert about his feelings around production, censorship, and AIDS.

Crawford Barton: AIDS forces you to get serious, to pick up your pace, to get rid of the nitpicking pre-occupying your time when you think you have all the time in the world. You have to boil it down to say: “That there’s not important. I have something important to do over here.” Work is the only thing that makes me happy anymore. I can’t just go to the beach and waste time. I have to read a book or write something. Wasting time makes me feel very unhappy. So I just get down into the work.

Jack Fritscher: Robert had this sense, this urgency, about him even before AIDS. He was propelled by drugs, ambition, and the joy of working.

Crawford Barton: In the 70s, I medicated myself to enhance my work so I could be less hung up. The result was non-productive.

Jack Fritscher: Have you thought about the effect of AIDS on the artistic personality? Can AIDS be a source of gay art?

Crawford Barton: My physical reaction is to view AIDS as a reality, but not a reality I want to capture in my camera. Robert didn’t take AIDS pictures and neither do I. I refuse to take ugly, creepy pictures of people with spots and withering away. That’s not my bag.

Jack Fritscher: He took self-portraits, almost time-lapse photos, of himself withering away.

Crawford Barton: Oh, yeah. I forgot about that. I may have blocked that out. The one of him looking about twenty years older all of a sudden. [Self-portrait with Skull Cane, 1988]. I am trying to continue on and get down to the essence of my work. I’m trying to distill my work to its core essence to expand it into something new rather than keep making infinite variations of what I did before. I’d rather do that, simplify and expand my visions, rather than switching my whole thing to AIDS pictures.

Jack Fritscher: Are you now trying to capture in a single frame what you captured before in a series of images? Your own “perfect moment’?

Crawford Barton: Yes. Not that I don’t still like sequential work. You could say I’m in search of the perfect moment, of doing it better, but I’m not searching any longer. I’m making each shot count more than I used to. The clock is ticking. I know how to make each shot count for more. My life is not like taking lecture notes in class any longer; it’s about taking the final test.

Jack Fritscher: I think Robert did that same sort of creative distillation in his head all his life. His social life and his sex life were rehearsals for his pictures. What would you think if a model felt Robert misrepresented him, processed his face inside his camera into something beyond the personal? Like people who feel the camera steals souls. Is photography exploitation? The camera is a gun and the sitter sits like a target in the gunsite. He shot me, but are those single frames me? He Mapplethorped me. His perfect moment might not have been mine.

Crawford Barton: In relationship to models, all photographers including myself must deal with models who have egos and personalities that rise up the minute I set up the camera between us. That’s why I like shooting Larry [Lara] and friends who understand how to make art.

Jack Fritscher: Inexperienced models like Robert shot maybe think you’re shooting them personally when you are aiming for the platonic ideal of them, or, at least, the mystique you see in them.

Crawford Barton: Robert had to get releases from his models. There was a formal transaction. Whether he got the releases before he began to shoot, I don’t know. They trusted him so he didn’t exploit them unless they thought so.

Jack Fritscher: Like someone who regrets the sex they consented to the night before.

Crawford Barton: Anyone who is willing to be the subject for an artist has to be open ended about it.

Jack Fritscher: The person has to trust the photographer?

Crawford Barton: Yes. Otherwise they’ll be uptight and the photographer won’t get anything.

Jack Fritscher: That says something about the celebrities who trooped in front of his cameras as certainly as they did. [Arnold Schwarzenegger, 1976; Richard Gere, 1982; Andy Warhol, 1986; Yoko Ono, 1988]

Crawford Barton: They obviously trusted how he would present them. They wanted to be, as you say, Mapplethorped.

Jack Fritscher: The famous liked sitting for someone famous.

Crawford Barton: Yes. That’s an age-old relationship. He didn’t choose the celebrities as much as they chose him.

[Barton shot a portrait of Lawrence Ferlinghetti, founder of San Francisco’s City Lights Bookstore, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, in 1974, and several portraits of gay actor Sal Mineo a year before Mineo was stabbed to death in Los Angeles: Sal Mineo, 1975, pages 68 and 69, DOH.]

Jack Fritscher: While the celebrity and fashion photos are exquisite, there seems to be more of Robert personally in his sex and flower pictures that were not commissioned.

Crawford Barton: The portraits of women and socialites don’t look as inspired as maybe the portraits he did of people he liked. I always revolted from shooting commercial stuff because I felt so “bought.” I would become so bored and bummed out and angry with myself for accepting assignments. I turned down many more jobs than I accepted. I knew I would hate it. So, I’m not very well off. In fact, I’m rather bohemian dirt-poor.

Jack Fritscher: Well, you sound happy. Robert thought money was a way of keeping score in America. He thanked his lucky stars he found a rich and smart patron. Sam and he were born on the same day of the year, twenty-five years apart. His luck had something to do with their astrology.

Crawford Barton: That’s one of the few things I do believe in: astrology.

Jack Fritscher: Have you looked at his Patti Smith photographs? What do you think of those as compared to his photos of Lisa Lyon?

Crawford Barton: Some of them with Patti were inspired. Some seem to be just trying to be weird, strange, vogue, just shadows of images. I don’t know her, but I feel she is a brilliant person with lots of insight, a visionary, and he realized that — if you can project “visionary” in a photograph.

Jack Fritscher: I think if it can be done, he and she collaborated and did it. I can see it in his lighting and framing of her face and posture. I don’t follow punk rock, but I read her book Babble and some other things she’s written and she’s clever.

Crawford Barton: I would compare her to Gertrude Stein.

Jack Fritscher: Someone told me Patti Smith is Gertrude Stein on drugs.

Crawford Barton: [Laughs] Which is a modern application.

Jack Fritscher: Gertrude ran a charmed circle and Robert liked the charmed circle he entered with Warhol and the Factory gang and Interview magazine. He was part of that 1960s-1970s world of art and commercial art.

Crawford Barton: At least, with Patti and Lisa, he didn’t perpetuate the traditional female image which I have always hated and refused to do: the romantic woman on a pedestal, the sex symbol, the beauty. He didn’t really perpetuate that. I always get angry when I go to movies. All of these romantic straight love stories and never any gay ones, or any sexy photography of men, although that’s changing and has changed a lot in the last decade.

Jack Fritscher: Is sitting for the camera acting or being? When looking at his pictures of Patti and Lisa, Patti seems more personally “Patti” whereas Lisa’s photos act out a more practiced pose about the faces and postures and power of women. He shoots Lisa, posing, from the outside in to capture her power as a platonic ideal. He shoots Patti, being, from the inside out to present her as herself.

Crawford Barton: Lisa is a bodybuilder and doesn’t depend on her intellect, at least not in his images. My most photographed model is like that. He perpetuates the myth that he is a dummy. He’s made himself into a living sculpture. He’s very clever and very resourceful. Making a living with minimal effort.

Jack Fritscher: You mean Larry Lara. You shoot him both ways — as your personal lover, the way Robert shot Patti, and, because of his muscular body like Lisa’s, as a platonic ideal of homommasculine perfection. He’s still a throb on Castro Street.

[Born in the South on a farm in Resaca, Georgia, seventy miles from Atlanta where he studied art at the University of Georgia, Crawford Barton, for whom male beauty was a fetish, groomed himself as a ruggedly handsome romantic archetype of the blond Confederate Captain very like Ashley Wilkes played by Leslie Howard in Gone with the Wind. He captured his own glory without vanity in Self Portrait, Dorland Street, San Francisco, 1974, page 8, DOH. Long-haired and bearded and hot and beautiful himself, he set out to shoot beautiful men motivated by Diana Vreeland writing at Vogue about “Beautiful People” and the Beatles singing, “How does it feel to be one of the Beautiful People.”

While he shot hippies, dykes on bikes, leathermen [Julian Turk, 1976], Castro clones [All-American Boy, 1977], trans-persons, San Francisco cops, Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence (a nun speeding past a MUNI bus on a motorbike in full habit with veil flying, page 35, DOH), Pride marches, and Harvey Milk, he specialized in lensing the hottest of the hot A-List hunks in the City as in his candid classic frames of a dozen men perched on window ledges, provisionally titled here as The A-List Lords on the Second-Floor Ledge (overlooking the Castro Street Fair), 1978, and in his staged series Castro Street, Men in a Truck, 1978, which is one of the most accurate documentations of how entitled super-hot guys looked and acted in the 1970s.

It was apt high concept to title his 1976 book of men on Castro Beautiful Men. Crawford described Lara, his main subject, as the “perfect specimen, as crazy and wonderful and spontaneous and free as Kerouac. So I’m never bored and never tired of looking at him.” Larry Lara (May 16, 1949 - January 9, 1992), whose pictures fill DOH, died age 42 from AIDS eighteen months before Barton died age 50, June 12, 1993.]

Jack Fritscher: Larry is marvelous. Who hasn’t lusted after that face and body?

[On October 3, the day after this interview, Larry Lara arrived at my home and studio driven by his bodybuilder boyfriend Larry Perry, the hottest bartender at the Spike in LA, whom I’d hired to star in my newest Palm Drive video feature, Naked Came the Stranger. Lara, in an open relationship with Barton who got off shooting many photos of Lara with many other men, helped Perry get into character on set, and he signed his name as witness to Perry’s signature on the model release.

I’d long been acquainted with the genial Lara who let me run a couple minutes of video on him outside on my deck. He didn’t know I was screen testing him as a potential model, but he seemed more suited to pose for still photography than act in a solo video where he had to move and talk and hold down the screen himself. A still frame may be truth, but video exposes truth at 30 times per second.]

Crawford Barton: Larry has a strong sense of what it takes to survive.

Jack Fritscher: Why is he your most photographed model?

Crawford Barton: Well, I’ve always been in love with him. We’ve been friends for years and years. I never get tired of looking at him. He was physically beautiful when I met him and has a great physique.

Jack Fritscher: So you have a personal lover’s connection with your muse, the same as Robert and Patti, would you say?

Crawford Barton: I think so. I don’t know if they were lovers, physical lovers.

Jack Fritscher: No one but Patti knows.

Crawford Barton: I don’t know if Robert slept with women or not. I’ve never really read a biography of him.

Jack Fritscher: Only the women would know. As to books, there aren’t any. That’s why I’m writing this book.

Crawford Barton: So you’re doing research into his background?

Jack Fritscher: As a pop-culture journalist, I have absolutely no intention of writing a biography of Robert per se. We live in an age of deconstruction. My memoir will be that, an offbeat pop-culture memoir, but not just my memoir. That’s why I’m collecting the “memoirs” of artists who knew him. He’s been dead for nineteen months. If these eyewitness testimonials aren’t collected right now before their stories turn his myth into legend, people will forget the honest truth they felt about him and his work the moment he died.

Crawford Barton: I met him briefly.

Jack Fritscher: I remember. Robert and I went with Thom Gunn [British poet, 1929-2004] to the opening of your exhibit at the Ambush bar. Do you remember that Robert Pruzan [1946-1992] shot a photo of Mapplethorpe, Gunn, and you standing in the late afternoon sun outside the Ambush?

[In 1994, I published that Pruzan photo in my book Mapplethorpe Assault with a Deadly Camera. In the picture, the trio’s clothing reveals the kind of diversity drag Walt Whitman liked in each one’s fetish identity in their costumes: Thom in an original Levi’s jean jacket, Robert in a bespoke leather jacket, and Crawford in an Army Surplus denim military shirt.]

Crawford Barton: Oh, yes. The late 1970s.

Jack Fritscher: He came to see your work. What was that like?

Crawford Barton: It was cool. He affected me and my work a lot. He was aloof, withdrawn, quiet, didn’t appear to be a happy outgoing person, dark and mysterious.

Jack Fritscher: He struck you as being unhappy then?

Crawford Barton: He didn’t strike me as being desperately unhappy, just withdrawn, in his own world. I was surprised when I went to one of his exhibits and he was there, and he was doing a lecture, and he looked like he was uncomfortable doing it but he was forcing himself to. The show was the S&M stuff. It was at the Lawson-DeCelle Gallery on Langton. He was going to do it if it killed him, because he “had” to.

Jack Fritscher: I was there with him that night. Rink took several great pictures of us there. Robert and I had just had supper at Without Reservation on Castro with Lisa Lyon, Jim Enger [my bodybuilder lover of three years who posed for Robert] and Greg Day [New York and San Francisco photographer and college roommate of Enger], and we all arrived together tangled up in the back seat of a taxi. Robert was snorting MDA. He was a bit stoned. I remember him bitching about all the boring people he’d have to meet. His little talk answering questions was part of his show on the road, part of the “sell.”

Crawford Barton: He was very interesting, but I got the feeling he might scream and run out of the room at any minute.

Jack Fritscher: I don’t want to wear you out and wear you down. I think you, as a photographer, have given me a good picture of your feelings about him.

Crawford Barton: I hope I wasn’t too negative.

Jack Fritscher: Not at all. Your memories belong to you.

Crawford Barton: I was trying to be honest. Robert and I were two very different personalities aiming in the same basic direction which is fine art.

Jack Fritscher: Despite some small commercial envy of his success, you felt close to what he was doing and could identify with it?

Crawford Barton: Oh, totally. I myself would never go in the direction he did, although I might have shot black men. I wasn’t interested in naked women. I was interested in naked black men, sexual practices, and erotic images.

Jack Fritscher: Your point of view means so much. This has been great.

Crawford Barton: If you think of anything else when you go back over this, let me know. And please rearrange anything I’ve said to clarify it.

Jack Fritscher: That kind of gentle editing I do, if at all, very carefully and minimally. I try to be holistic.

Crawford Barton: I know how much trouble and how time-consuming it is to put something on paper from a tape.

Jack Fritscher: Exactly. Thank you for your time and your excellent insights into your own work. And into Robert. You said you’ll be gone until October 28. When you return, let’s get together again. I’d love to see some of your newest pictures and also some of your Super-8 films. If you want to get out of town, perhaps you can come visit and see my garden which is still blooming with a hundred of my six-foot-tall calla lilies that Robert thought were amazing.

Crawford Barton: That sounds perfect to me.