NON-FICTION BOOK

by Jack Fritscher

How to Quote from this Material

Copyright Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. & Mark Hemry - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

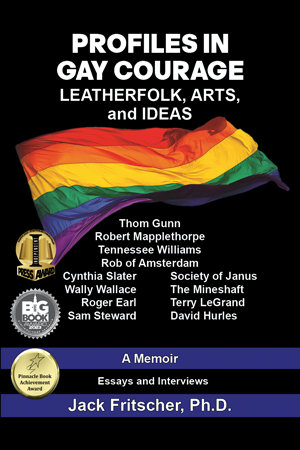

PROFILES IN GAY COURAGE

Leatherfolk, Arts, and Ideas

Volume 1

by Jack Fritscher, PhD

SAMUEL STEWARD

1909-1993

The Talented Mr. Steward

San Francisco’s Connection to the

Gay Bestseller Shocking the Nation

Secret Historian: The Life and Times of Samuel Steward, Professor, Tattoo Artist, and Sexual Renegade,

by Justin Spring, 478 pages

In transparency, rather than review the brilliant Secret Historian, I can best, as a San Francisco SOMA historian, give heads-up endorsement of my friend Justin Spring’s important and authentic biography of my longtime friend Samuel Steward. Born in 1909, Steward defied the stress of the anti-gay century when owning one gay photograph meant jail. He defiantly documented gay culture in his books, sex diaries (1924-1973), tattoo journals, and activist input to his beloved mentor Dr. Alfred Kinsey at the Institute for Sex (1949-1956).

Spring chronicles Sam’s anxiety-driven life that was an existential pile-on of family dysfunction, literary ambition, alcohol, celebrities, speed, hustlers, censorship, inter-racial S&M, rage against ageing, and a soul shared with an unborn twin in his left testicle. As Gertrude Stein warned her “dear Sammy,” his every gorgeous vice sliced away at his self-esteem until he died December 31, 1993.

New York author Spring was researching his book Paul Cadmus: The Male Nude when in 2001 he discovered the “cold case” of Steward stored in a San Francisco attic. Since 1969, I have been eyewitness to Steward’s story, and can testify to the pitch-perfect authenticity of Spring’s character study which downloads Sam’s analog diaries and letters without overpowering his outrageously risque voice.

At Stonewall, gay character changed. Reading Secret Historian, you see why it had to. And, why, if it hadn’t, you’d still be in the closet.

Sam Steward, famous for his pen name as the artful dodger “Phil Andros,” was a bon-vivant chum whose life, like Christopher Isherwood’s, was a cabaret. Sunbathing in France in 1938 with Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, fleeing Nazis by ship, he was an ambitious boy from Ohio who knew how to sing for his supper at the tables of Stein-Toklas, Thornton Wilder, Oscar Wilde’s lover Bosie, George Platt Lynes, Tennessee Williams, Kenneth Anger, the Hells Angels, and, even, my lover Robert Mapplethorpe and me when Steward joined what he playfully dubbed our “Drummer Salon” which included San Francisco poets Ronald Johnson and Thom Gunn.

Author Steward, always pursuing publishers to print his “Phil Andros” stories, loved Drummer, San Francisco’s longest-running gay magazine which resurrected his career. When I put him in touch with the founding Los Angeles editor-in-chief Jeanne Barney, she revived two of his previously published stories: “Babysitter,” Drummer 5, March 1976, and “Many Happy Returns,” Drummer 8, August 1976. As the founding San Francisco editor-in-chief, I printed his new cop-fetish story, “In a Pig’s Ass,” in Drummer 21, March 1978, and his Catholic short story “Priest: This Is My Body” in my Drummer spin-off zine Man2Man Quarterly 2, December 1980.

From my editorial desk for February 9, 1978, Drummer art director Al (A. Jay) Shapiro and I arranged an iconic dinner party “mixer” at the home of leather-priest Jim Kane and chef Ike Barnes who later managed Sam’s eldercare. Our five guests, whom we introduced to each other for the first time, were individually famous Drummer contributors: Sam Steward; Tom of Finland and his lover Veli on Tom’s first visit to America; Oscar streaker Robert Opel, founder of SOMA’s first gay gallery Fey-Way; and my lover Robert Mapplethorpe with whom Steward shared a taste for kinky Polaroids and black men. I watched Steward, a graduate of Stein’s “Charmed Circle,” glow in the convergence of the kind of shining company he had adored since youth.

In 1972 on audiotape Sam told me when he was seventeen in 1926, he knocked on the hotel door of silent-screen star Rudolph Valentino, walked in, and blew him while sneaking snips of the actor’s pubic hair with a manicure scissors. When Valentino died later that year, Sam enshrined the film icon’s short-and-curly Italian DNA in a gold reliquary he kept forever. He showed it to me like a sacred relic. Some may doubt his teen movie-fan story, but that was the moment when he started creating documentation of his sex partners, writing sex stories, and collecting a fetish hoard of police patches. His gay trophies piled up in his Berkeley cottage, and then in the San Francisco attic of his executor, expert librarian Michael Williams.

Steward, immensely generous to friends, romanced straight women; adored lesbians; fetishized black, Latino, and straight men; and spouted Old School queer theories knocking the “fake masculinity” of the new generation of post-Stonewall leathermen. He chased Gide and Genet, ran from James Purdy, balled Rock Hudson, tattooed James Dean, and adapted his novel $tud as the screenplay, Four More Than Money, for San Francisco filmmaker J. Brian. His sex-tourist diaries of San Francisco (1953-1954) give eyewitness to local bars, baths, and “sailor sex” so wild at the Embarcadero YMCA he was banned from Y’s everywhere.

As a popular university professor and zealous masochist (1930s-1980s), he worshiped students and rough-trade Navy seafood. To get his hands on young recruits, he learned tattooing and, while still teaching university classes, opened “Phil Sparrow’s Tattoo Joynt” (1956-1963) in a sleazy Chicago arcade with coin-operated sailors whom he paid thousands of dollars at three bucks a pop. Wrongly accused of child murders, he fled west to Oakland, opening his “Anchor Tattoo Shop” (1964-1970) where the Hells Angels adopted him.

Inking 150,000 men, Steward pioneered today’s tattooing style, mentoring young San Franciscan Ed Hardy and Chicago leatherman Cliff Raven who, like Steward, was intimate inside Chuck Renslow’s Chicago Family. Spring reveals that Steward documented how Renslow, the great unrequited love of his life, and the artist Etienne organized their business ventures of 1950s homomasculine leather culture around their Kris Studio physique models, their Triumph and Mars magazines, their Gold Coast bar, and their 1960s physique contests that evolved into their annual International Mister Leather contest (IML).

Steward and I met in 1969 when he was sixty, and I was thirty. With Kinsey dead since 1956, we both feared he might die without a post-Stonewall update. Circumstances made this university professor who was there for him the first gay scholar to interview him. Our 1972 session was recorded in his Berkeley cottage on Ninth Street just before the Advocate, the Bay Area Reporter, Drummer, and gay book publishers existed, and a dozen years before younger writers such as Joseph Bean, John Preston, and Gayle Rubin paid him court.

Their keen literary crushes on him in the 1980s bucked up his self-esteem the way he had felt validated by my government arts grant to record him in 1972 for the Journal of Popular Culture. After our interview, he put a fly in our fun that was really rather charming. And understandable. He stipulated I never use his recorded narrative while he was alive, “because I have to live off my story.” He meant dinner parties, autobiographical essays, and university lectures.

On my digitized audiotape, Sam’s voice rings as clear as in Spring’s perfect narrative. He spoke frankly about his literary life, affairs, beatings, arrests, and divine lunches in Paris, Rome, and San Francisco. He smoked his cigarettes, tilted his glass, and told his oral history of sex, intrigue, revenge, and literary gossip in phrases so authentically measured word for word that I realized he had long ago rehearsed and decided precisely how his story should be told.

I believed every vivid word Sam said, and loaned my thirty-year-old transcripts to Justin Spring who, empowered by Michael Williams’ salvific attic archive, fit eighty-four years of Steward’s drama into his astute and charming book that finds — and here’s its human value — a universal gay story in Sam’s specific life.

Steward would have loved Spring. Resurrected once again, through Justin, Sam sings for his supper. Secret Historian succeeds as an amazing cautionary tale and awesome depiction of how gay men built up the gay courage to construct personal survival tactics against all odds in the homophobic last century before and after Stonewall. Justin Spring’s entertaining page-turner with its strong narrative plot and fierce characterizations deserves to be made into an art-film biopic of the kind international gay film festivals applaud. Til then, Sam’s story is perfect bedside reading.

* * * *

April 10, 1994

Friends of Sam Steward are invited to meet one another on Sunday, April 10, 1994, from 3:00 to 5:00 PM at Sam’s favorite restaurant, Le Bateau Ivre [named after Rimbaud’s teenage poem, “Le Bateau Ivre”/“The Drunken Boat”], at 2629 Telegraph Avenue, Berkeley, California, to share memories and the joy we have had in knowing Sam. Refreshments will be provided. There is no need to RSVP, but for information, call Michael Williams at [phone number]. Also you might let me know if you need a ride or could provide one.