INTERVIEW of

JACK FRITSCHER

HONCHO Magazine Vol 18 No 4 April 1995

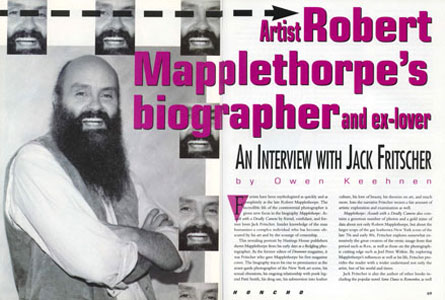

"Artist Robert Mapplethorpe's Biogragher and Ex-Lover"

by Owen Keehnen

Artist Robert Mapplethorpe's Biographer and Bi-Coastal-Lover

An Interview with Jack Fritscher

Few artists have been mythologized as quickly and as completely as the late Robert Mapplethorpe. The incredible life of the controversial photographer is given new focus in the biography Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera by friend, confidant, and former lover Jack Fritscher. Insider knowledge of the man humanizes a complex individual who has become obscured by his art and by the scourge of censorship.

This revealing portrait by Hastings House publishers shows Mapplethorpe from his early days as a fledgling photographer. As the former editor of Drummer magazine, it was Fritscher who gave Mapplethorpe his first magazine cover. The biography traces his rise to prominence as the avant-garde photographer of the New York art scene, his sexual obsessions, his ongoing relationship with punk legend Patti Smith, his drug use, his submersion into leather culture, his love of beauty, his theories on art, and much more. Into the narrative Fritscher weaves a fair amount of artistic exploration and examination as well.

Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera also contains a generous number of photos and a gold mine of data about not only Robert Mapplethorpe, but about the larger scope of the gay leathersex New York scene of the late 70s and early 80s. Fritscher explores somewhat extensively the great creators of the erotic image from that period such as Rex, as well as those on the photographic cutting edge such as Joel-Peter Witkin. By exploring Mapplethorpe's influences as well as his life, Fritscher provides the reader with a wider understanding not only of the artist, but of his world and times.

Jack Fritscher is also the author of other books including the popular novel Some Dance to Remember, as well as erotica collections such as Stand By Your Man and the novel Leather Blues. He was co-publisher of the popular early zine MAN2MAN Magazine, founder of The American Popular Culture Association, and is currently involved in the operations of the entertainment company, Palm Drive Video.

Recently I had the opportunity to talk with Jack Fritscher about the biography. He's an interesting man, a solid and intriguing blend of theory and knowledge. We discussed Mapplethorpe at length, and touched upon such other personalities as Patti Smith, Andy Warhol, porn legend J.D. Slater, and even Robert Opel, the slain performance artist who streaked behind David Niven and Elizabeth Taylor at the 1974 Academy Awards.

Owen Keehnen: When and where did you meet Robert Mapplethorpe and what was your first impression?

Jack Fritscher: In 1977 Robert walked into my office in San Francisco when I was editor of Drummer. I had no idea who he was. He said,"Hi, I'm Robert Mapplethorpe the pornographic photographer." He wanted to be known as a bad boy. I thought he was cute and then he opened his portfolio and these gorgeous photos spilled out. That was when the big party was going on in the golden age before everything crashed. At that time painters weren't painting and photographers weren't shooting and singers weren't singing...everyone was out having sex. It was difficult to fill an entire magazine. The situation is very different today. Anyway, I told him I needed a cover for an upcoming issue. I was taking cigars out of the manly closet where they had been and was moving them overground. I sketched what I wanted for him and gave him the name of Elliott Siegal, a friend of mine, whom Robert went and shot. From that came Robert's first magazine cover, and it made him eternally grateful.

Owen Keehnen: What impressed you about his finished product on that assignment?

Jack Fritscher: He got the concept of what I wanted for the issue because he understood fetish. He knew how to take something that could be considered disgusting and make it hot. Specifically, he understood how to get the sweaty leathery cigar thing I wanted out of Elliott. Robert ended up using him a number of times. He was the first of many models I got for Robert.

Owen Keehnen: Any idea what that September, 1978, issue of Drummer is worth today?

Jack Fritscher: I believe around $65-$100--if you can find one.

Owen Keehnen: In Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera you speak of his obsession with sex, quite graphically at times. Do you think he was obsessed with sex or the taboo it presented?

Jack Fritscher: He was very obsessed by sex. In the letters I received from him he refers repeatedly to being obsessed with it. He truly was. I thought he needed a psychiatrist because he was so obsessed. He was destroying his life and health and fortified his obsession with drugs so he could have even more of it. However, he was also obsessed with beauty. He could not not do sex and he could not not do beauty--if you run those two obsessions together you come up with these cleaned up and perfect moments...like capturing the ideal sex act.

Owen Keehnen: What were the best and worst parts about being his lover?

Jack Fritscher: He was great, a sweet guy. People ask me, "How could you have an affair with someone who used a bullwhip suppository?" But that wasn't Robert, that was him fictionalizing himself. That's why I included pictures in the book taken by myself and others, because a different Robert comes across than the ones in which he's merchandising himself.

Owen Keehnen: What was the importance of his self portraits?

Jack Fritscher: They were the creating of the Mapplethorpe legend.

Owen Keehnen: How much did he market controversy and play the role of bad boy of the New York art scene?

Jack Fritscher: He was naturally controversial, but he never had the opportunity to market his greatest controversy--the cancellation of his show by Congressional censors at The Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C....at that time he had been dead for eighty-five days. Controversy meant money to him and because he was deeply American, money was also a way for him to keep score. He could be very polite and "in-your-face" at the same time. He would take a photograph and if you were a client he'd hold it up to you and say "What do you think of this?" and if you blinked or flinched he would say, "See, you're not as avant-garde as you think you are." So he kind of blackmailed people by his presentation of art. He wasn't a soft sell.

Owen Keehnen: They've been called alter egos, soul-mates, lovers, and other things, but what was the essential link between Mapplethorpe and punk pioneer Patti Smith?

Jack Fritscher: The essential one is that they were soul mates. It was a playing with that early punk and androgyny, and in playing with it they referenced each other. Robert wanted to be a rock star, that's why he posed that way in the George Dureau photograph on the cover of this biography. He was going for a Mick Jagger attitude in that photo, but he idolized Jim Morrison, too. Patti had the musical career Robert wanted and Robert had the photographic career that Patti wanted. In an account by Edward Lucie-Smith, he said he invited Patti up when she was in England and she was wandering around with a camera trying to be Marianne Faithfull shooting rockstars. She was part of the scene, but I think she thought she should be a photographer the way Robert thought he should be a rock star. They played off each other. If they were both heterosexuals they would have been perfect for one another. His photographs of Patti hanging on those pipes stoned on MDA early on, and then in later pictures her portraits in a state of glorious, almost pieta, mourning are both incredible. She is the Mrs. Robert Mapplethorpe the straight world wished he had.

Owen Keehnen: Why is that?

Jack Fritscher: Because if they could straighten him up they would be making money off all kinds of stuff. That's why they want the "middle Mapplethorpe," the leather Mapplethorpe, the gay Mapplethorpe to go away. If you want to sell china plates with calla lilies on them it's pretty difficult to put the sex thing aside because you wonder, "Are those just pictures of flowers, or are those the genitalia of a flower...and can I eat my canape off of that?"

Owen Keehnen: Taking a different approach to his controversial nature, could you explain his intrigue with photographing black men? Was he racist?

Jack Fritscher: His pattern with leather, women bodybuilders, black men, and even women themselves was that Robert was looking for forbidden material that had never seen the overground light of day. Leather was underground material he wanted to take and clean up and present. He had the perfect form under control. He knew how to take the great photograph, what he needed was diversity of content. The leather scene, bodybuilding, and blacks had not been seen very much in photography on this level. So he brought black men forward, so to speak. He did have an erotic attraction for black men and he eroticized them for himself, but he also eroticized female bodybuilder Lisa Lyon. He eroticized the leather scene too. His obsessive personality eroticized life and his passion made his subjects icons because of his Catholic background. The leather scene reflected his Catholic background with martyrs suffering and strung up and flayed and things.

Owen Keehnen: How was this reflected in his photos of African-American men?

Jack Fritscher: With African-American men he really got into the nitty-gritty of it all. From the first, he was accused of being racist, but that claim falls into the same category as when a man takes a nude photo of another man, it's automatically homosexual, and when a woman does, it is not. When a white man takes a photo of a black man, it's labeled racist. People jump to judgments that aren't true. Robert, when he used the word 'nigger', used it on an inside track the way blacks often use the term affectionately to refer to one another. Racism is hate; Robert did not hate black people at all. He loved--even worshipped-black men.

Owen Keehnen: Stressing an earlier point, how much of his vision and art were the result of his Catholic up bringing?

Jack Fritscher: All of it. It's all premised on Catholicism. It's the keynote of his work. He was a true Catholic gay man functioning as an artist in America. He takes the New York spin, the gay spin, the American spin, and the fundamental Catholicism of the rosary, the stations of the cross, the martyrology, The Blessed Virgin, and icons, and blends them all together. The first thing he gave me was a photo of himself composed in such a way that he could be lying on the cross. The symbolism of Catholicism and Christianity were his subtext.

Owen Keehnen: In the book, you put his photos into five categories: Patti Smith, African American men, leathersex, celebrity and fashion, and still-life flowers and objects. Which of these brought him the greatest artistic fulfillment?

Jack Fritscher: I think everything he shot was a still life because he was trying to catch everything in that perfect moment. Patti Smith was more personal, but he also used her as part of his iconography. He loved shooting friends, many of the black men and leather photos, the Patti Smith photos, as well as some of the celebrity and fashion work.

Owen Keehnen: What celebrities did he enjoy photographing?

Jack Fritscher: He loved photographing Arnold Schwarzenegger because he was a kind of endorsement. Schwarzenegger had appeared at The Museum of Modern Art as living sculpture and it was Robert's first photograph that he sold to a private collector. He saw the celebrity line was the way to go. He liked Susan Sarandon a lot because I think of all the women he shot most were photographed as almost sleeping beauties. Often he's luxuriating in the richness and indulgence of a woman able to be passive, not as an object, but as reflective of a society where women can be thought of as beauty incarnate. In contrast, his photo of Susan Sarrandon is the most active. Instead of lying back before Robert Mapplethorpe's focal power --which he certainly had behind the camera--she's holding the sheet to her breast and rising up from the bed. It's all the power of Venus rising from the sea. She is a wonderful woman rising to what she can be.

Owen Keehnen: As a subject yourself, could you explain the experience of being photographed by Robert Mapplethorpe?

Jack Fritscher: Robert could put you in front of a camera and peel the layers off of you like an onion. The worst thing for me was that he liked to photograph me after a night at The Mineshaft because he thought maybe enough of that action would peel me down to the look he wanted to bring out. He said he wanted to see the devil in us all. That famous Mapplethorpe 'raccoon' effect you can only have at certain hours of the dawn. He'd sit you down and the camera would be there and he wouldn't mold or move you, but adjust you. The truth of the person was sitting there, but again he wanted the perfect moment of the truth. Adjustment took only a moment and then "click, click, click." It was over before it even started.

Owen Keehnen: Any good portrait tales?

Jack Fritscher: When Surgeon General Koop came to the studio it was hilarious because Robert was still smoking, still taking drugs, and was sick himself. Koop came and Robert was shoving his cigarettes into a drawer and using breath cleansers. He did try to accommodate himself to the sensibilities of the people he was shooting.

Owen Keehnen: Given the choice would he rather have been an artist or a celebrity?

Jack Fritscher: He was born an artist. He was an artist who picked up a camera as a medium because it was fast paced. Sculpture was much too slow. He was an artist who wanted celebrity because photography as a medium is very expensive. It requires money to get the right camera and film and processing, all of which he oversaw. Everyone locks in on the models and the camera, but there's a lot more to Mapplethorpe than that.

Owen Keehnen: In the book you draw frequent comparisons between Mapplethorpe and Andy Warhol. How, essentially, were they alike?

Jack Fritscher: They shared their background in Catholicism, their sense of replacing biological families with an art circle that became a family. They shared the commercial side, meaning how do you create as much art as possible. Warhol's taking something like the Campbell's soup can and turning it into art, made art reproducible. Pop art and photography are essentially democratic because only one person can own a painting, but something that's forever reproducible is not the same thing. Both realized they could make money by mass marketing. I think it would be perfect if someone took Robert's photograph, "Mr. 10 1/2," and put him on a bed sheet. It would sell great in The Castro and on Christopher Street.

Owen Keehnen: There's a story there too...

Jack Fritscher: Yeah. I don't know if people know this but Mr. 10 1/2, Mark Stevens, was a very famous porn star in the 70s. Robert considered it a celebrity photograph. Mark Stevens had an entire career but the overriding Mapplethorpe connection has dissolved who he was.

Owen Keehnen: Speaking of porn stars, you are also a close friend of J.D. Slater. Tell me something about him I wouldn't necessarily expect.

Jack Fritscher: I love him dearly. He's wild and funny. He's the most consistently witty man I have ever met in my life.When I sent him a copy of the book he said, "Jack, it's wonderful, but I broke it trying to shove it into my VCR."

Owen Keehnen: And so sexy too. Going back a bit, you were also on the periphery of the Warhol scene. What was your take on Andy?

Jack Fritscher: I was very young when I knew him. I thought he was weird. I was new to that whole scene and passing in and out of The Factory. He had that white albino wig and sort of looked like he needed a shower. He looked like he needed to be cleaned up, like somebody put him together or like a doll to be dressed. He was so conceptual and he would walk around in this conceptual daze. He'd say "Oh I think we ought to do this or that, or go create Interview, or he's very pretty, give him some drugs and let's make a movie of him." There were so many artists around him that he would conceptualize these things and they would go out and execute it. That's how he created so much work.

Owen Keehnen: In the book you interview many of Mapplethorpe's contemporaries as well. There are pieces on various photographers and personalities of the performance and art scene such as Joel-Peter Witkin, Rex, Camille O'Grady, and someone who fascinated me, Robert Opel. He was the artist who streaked behind Elizabeth Taylor and David Niven at the 1974 Academy Awards and was slain in his Fey Way Gallery in 1979. What was his take on that Oscar night?

Jack Fritscher: As soon as I found out that was him I said, "Tell me everything." It's a great American pop culture story. Security is everywhere now, but at one time there wasn't much anywhere, even at the Academy Awards. He was able to work his way into the auditorium and back-stage where he hid inside a huge piece of scenery. He said he thought he was going to die in there because there were electrical cables feeding all around him and he had to stand on them and at any moment they would move around. He waited specifically until Elizabeth Taylor came out because he thought if he was going to do it, what greater movie star? I asked him if he was part of any sort of inside joke because David Niven was so quick witted, but Opel said that he was on his own and that he did it as a piece of performance art.

Owen Keehnen: In 1990, you published your well-received novel Some Dance to Remember, a gritty and sexy take on the gay and weight lifting scene from 1970-82. What was your trick for conveying the era so accurately?

Jack Fritscher: Everyone thinks Some Dance to Remember is autobiographical, but it's not. It's very flattering, I suppose, because it means it feels very real. What I tried to do was keep blinders on through much of the eighties so nothing beyond 1982 in vocabulary or style or music would enter my consciousness [during the final edit].

Owen Keehnen: You've also written several other books including the one-handed classic Stand By Your Man. What's essential to writing good pornography?

Jack Fritscher: Everyone today says we're going into an interactive phase of technology, but I would say anybody who's been writing pornography and is able to make people cum has been interactive since the beginning. That's what it's all about. If I can't make you cum in three paragraphs or less either I'm failing or you're impotent.

Owen Keehnen: What are you working on now?

Jack Fritscher: A work of fiction called My Fanatic Heart and Other Stories [editor's note: the novel later titled The Geography of Women was published in 1998] and also a piece of nonfiction. The nonfiction includes, in the same way this biography did, much of our times and chronicles the age. This work-in-progress pulls together even more people who didn't necessarily fit into the Mapplethorpe story but have a great importance in the history of gay arts and letters or just as interesting personalities.

Owen Keehnen: Good luck with both projects and thanks, Jack.

Jack Fritscher: Thanks, Owen.

Copyright: Owen Keehnen

|

|

||||||